Abstract

In 1596, ChosŇŹn ambassadors Hwang Shin ťĽÉśĄľ (1560-1617) and Pak Hongjang śúīŚľėťē∑ (1558-1598) joined the ill-fated mission to Japan to invest Hideyoshi as King of Japan and restore peace to the region. Hwang Shin‚Äôs diary is an important historical source for the breakdown of the peace negotiations, which resulted in the devastating invasion of 1597. The ambassadors‚Äô diaries also give detailed accounts of the alien country and the people who had visited such destruction on their homeland and yet were so little understood by people in Korea. Hwang‚Äôs diary particularly compares cultural norms and values in China, Korea, and Japan, revealing in the process what he thought about these countries and their places in the world.

-

Keywords: Imjin War, Hwang Shin, T’ongshinsa, Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Introduction

The years 1595-6 were the eye of the storm in the war between Japan, Korea, and China. An uneasy ceasefire held, as Ming China and Japan ostensibly moved towards a settlement to end the conflict. Many people at the time believed the war was finally coming to an end; still more hoped it was. With hindsight, we know that the fragile peace was to collapse and a second, even more wrathful invasion would commence the following year. But in 1596, everything was still uncertain, and all eyes turned to the diplomatic mission to Japan which promised a final resolution. This article follows the ChosŇŹn ambassadors on their journey from Korea into the unknown, exploring what their accounts tell us about that critical moment, as well as about Japan, ChosŇŹn, and the Ming more widely.

The diaries of the two ambassadors have both survived; those of Hwang Shin ťĽÉśĄľ (1560-1617), t‚Äôongsinsa ťÄöšŅ°šĹŅ ‚Äúofficial ChosŇŹn ambassador‚ÄĚ to Japan in 1596, alongside the diary attributed to Deputy Ambassador Pak Hongjang śúīŚľėťē∑ (1558-1598). Both Hwang and Pak were relatively high-ranking officials in the ChosŇŹn court, placing both men much nearer the political and cultural centre of their country than any of the other authors in this book. Hwang Shin, in particular, had received a very orthodox Neo-Confucian education, under the renowned teacher SŇŹng Hon śąźśłĺ (1535-1538), who had also been prominent at court. The diaries of the two men‚Äôs mission trace their journey from a familiar political and cultural space to a land utterly foreign to them. Recording their reactions each step of the way, the diaries offer an insight into how Hwang and Pak envisioned the border between ChosŇŹn and Japan, how they compared the foreign things and people they encountered to familiar ChosŇŹn and Chinese points of reference, and what they believed it meant for someone to belong to ChosŇŹn or Japan. Hwang and Pak‚Äôs accounts were then and remain now important pieces in the puzzle for anyone trying to understand the collapse of the peace process and Hideyoshi‚Äôs decision to order a second invasion.

Peace Process 1593-1596

In Beijing, plans to expel the Japanese from ChosŇŹn by force in 1592 had given way to the pursuit of peace negotiations by 1593.

1 Minister of War Shi Xing Áü≥śėü (1537-1599) received information that Hideyoshi was in fact seeking investiture as King of Japan and the right to send tribute missions (which represented a limited right to trade, as tribute missions doubled as trading parties). Shi saw an opportunity to bring to a swift end the extremely costly Eastern Campaign (as it was known in Beijing), and arranged for his informant and self-styled Japanese expert, Shen Weijing ś≤ąśÉüśē¨ (1537-1599), to travel to ChosŇŹn to begin negotiations with the Japanese in 1593.

Konishi Yukinaga ŚįŹŤ•ŅŤ°Ćťē∑ (1555-1600), the commander who had led the vanguard of the Japanese invasion, also began working for a negotiated end to the conflict soon after arriving in ChosŇŹn.

2 As for Hideyoshi, only a few months before he had been detailing plans of moving the Japanese emperor (GoyŇćzei ŚĺĆťôĹśąź, 1571-1617) to the Chinese capital and installing himself (officially only the

kampaku ťóúÁôĹ ‚Äď akin to prime minister) in the Chinese trading port of Ningbo. Yet, the reality of the battlefield seems to have forced him to abandon his grand ambition for conquest of China.

3 At a meeting in Nagoya, Hideyoshi‚Äôs representatives relayed his proposed terms for peace, which show him seeking to establish amicable neighbourly relations with the Ming dynasty, and a suzerain-vassal relationship with ChosŇŹn.

4 An end to the war seemed to be within reach, but there were several key points which remained unresolved. Knowing this, the group of negotiators led by Shen Weijing on the Ming side and Yukinaga on the Japanese side continued to work together in secret to filter both the Ming and Hideyoshi‚Äôs demands so that they appeared acceptable to the other and, inch by inch, nudge both sides towards an agreement. Shen Weijing spent extended periods in Yukinaga‚Äôs encampments, and the group succeeded in shutting out from their negotiations other Ming officials ‚Äď even the Ming ambassador ‚Äď as well as Yukinaga‚Äôs rival Kato Kiyomasa Śä†Ťó§śłÖś≠£ (1562-1611) and the ChosŇŹn court, which watched with consternation and apprehension.

5 Though observers on all sides were deeply sceptical ‚Äď and seemed to latterly be justified by the breakdown of the talks ‚Äď Yukinaga and the others evidently believed they had a credible chance of success. Indeed, they quite literally gambled everything on it: Shen Weijing was ultimately put to death for his failure, and Yukinaga narrowly escaped Hideyoshi‚Äôs wrath.

The culmination of the negotiators‚Äô plan was an official mission from the Ming dynasty to invest Hideyoshi as King of Japan. One of the Ming conditions for this mission had been the withdrawal of Japanese forces from the peninsula, though even by 1596 this still had not happened. This was one of the conditions that had been ‚Äėfiltered,‚Äô and Shen Weijing does not appear to have put this request to Hideyoshi until later ‚Äď as we shall see. Shen and Yukinaga evidently believed that Hideyoshi would agree to order a withdrawal if representatives of ChosŇŹn came to pay their respects to him.

6 This final requirement is what Keitetsu Genso śôĮŤĹćÁ饍ėá (1537-1611), a Japanese monk who had been one of the intermediaries liaising with ChosŇŹn since the build up to the war, relayed to ChosŇŹn official Hwang Shin. Genso explained the mission as being to ‚Äėthank‚Äô Hideyoshi for his mercy in releasing King SŇŹnjo‚Äôs two sons, who had been taken hostage at the beginning of the war.

7 Leaving aside the idea of expressing gratitude to their invader for his mercy, the ChosŇŹn court had no desire to resume diplomatic relations with Japan before extracting so much as an apology from the country they now viewed as their mortal adversary.

8 Hwang Shin turned first to Ming ambassador Yang Fangheng ś•äśĖĻšļ® for guidance, but Yang was concerned for his own safety and could not care less whether ChosŇŹn sent an emissary.

9 Shen Weijing, on the other hand, assured Hwang all would be well, and that he would ensure the ChosŇŹn envoys were not put in any awkward situations. Ultimately, as Genso pointed out (probably not without some satisfaction), ChosŇŹn had no choice but to comply, given that it was too militarily weak to eject the Japanese without help.

10

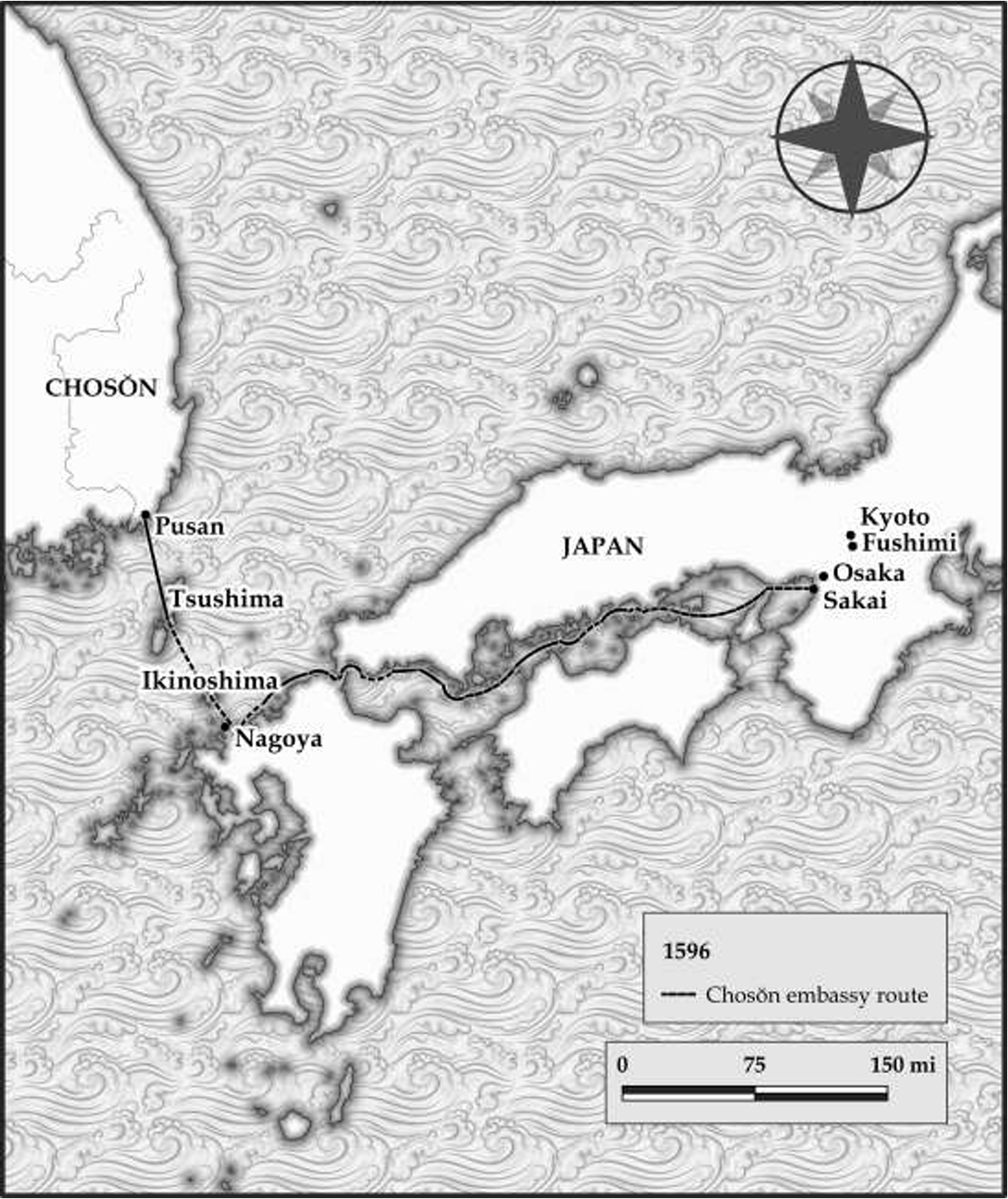

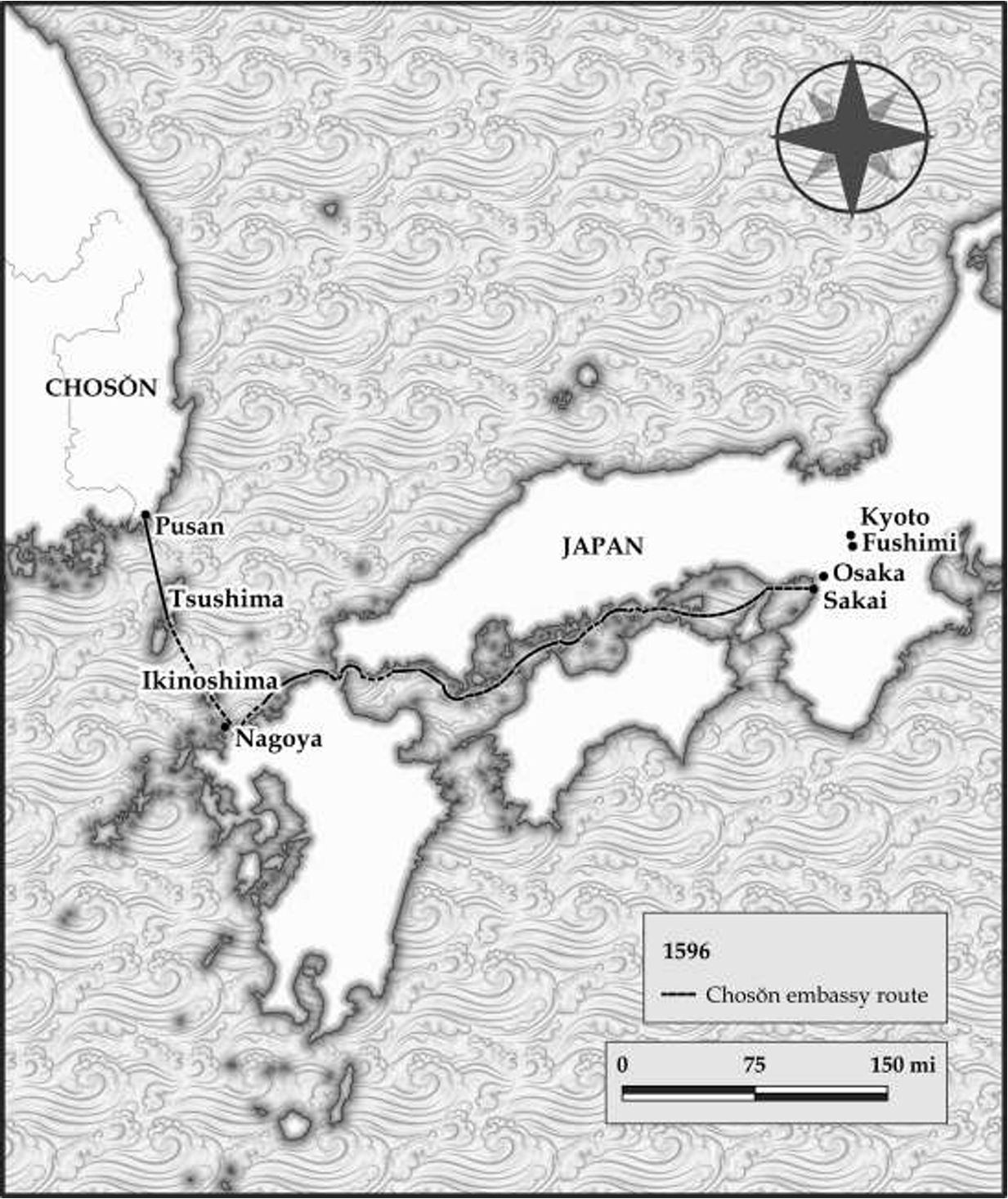

The ChosŇŹn court thus reluctantly appointed Hwang Shin as Chief Ambassador and Pak Hongjang as Deputy Ambassador. They were to lead a company of civilian and military officials, including Chinese and Japanese interpreters, servants, and slaves, numbering about three hundred in all. At the beginning of the eighth month of 1596, the company set sail from Pusan, heading for the port of Sakai Ś†ļ, near Osaka and the capital Kyoto, where Hideyoshi was waiting. Two diaries recording this journey have survived, and both begin shortly before the company set sail and end when they finally left the Japanese camp at Pusan to return to the ChosŇŹn court

.

Two Ambassadors, Two Diaries

The Diary of Hwang Shin

Hwang Shin was famed for his scholarly talents: he was a

changwŇŹn ÁčÄŚÖÉ, meaning he had come first in the highest level civil service examinations (in 1588). In 1591 his career suffered a temporary setback when he was demoted after becoming embroiled in factional politics, but he returned to office in 1592, employed to accompany the overall commander of Ming forces, Song Yingchang ŚģčśáČśėĆ (1536-1606).

11 Before being made ambassador in 1596, Hwang had spent many months accompanying Shen Weijing in the Japanese encampments, though for at least part of this time he was isolated and kept under guard, lest he spy on the camp or eavesdrop on Shen and Yukinaga’s secret meetings.

12

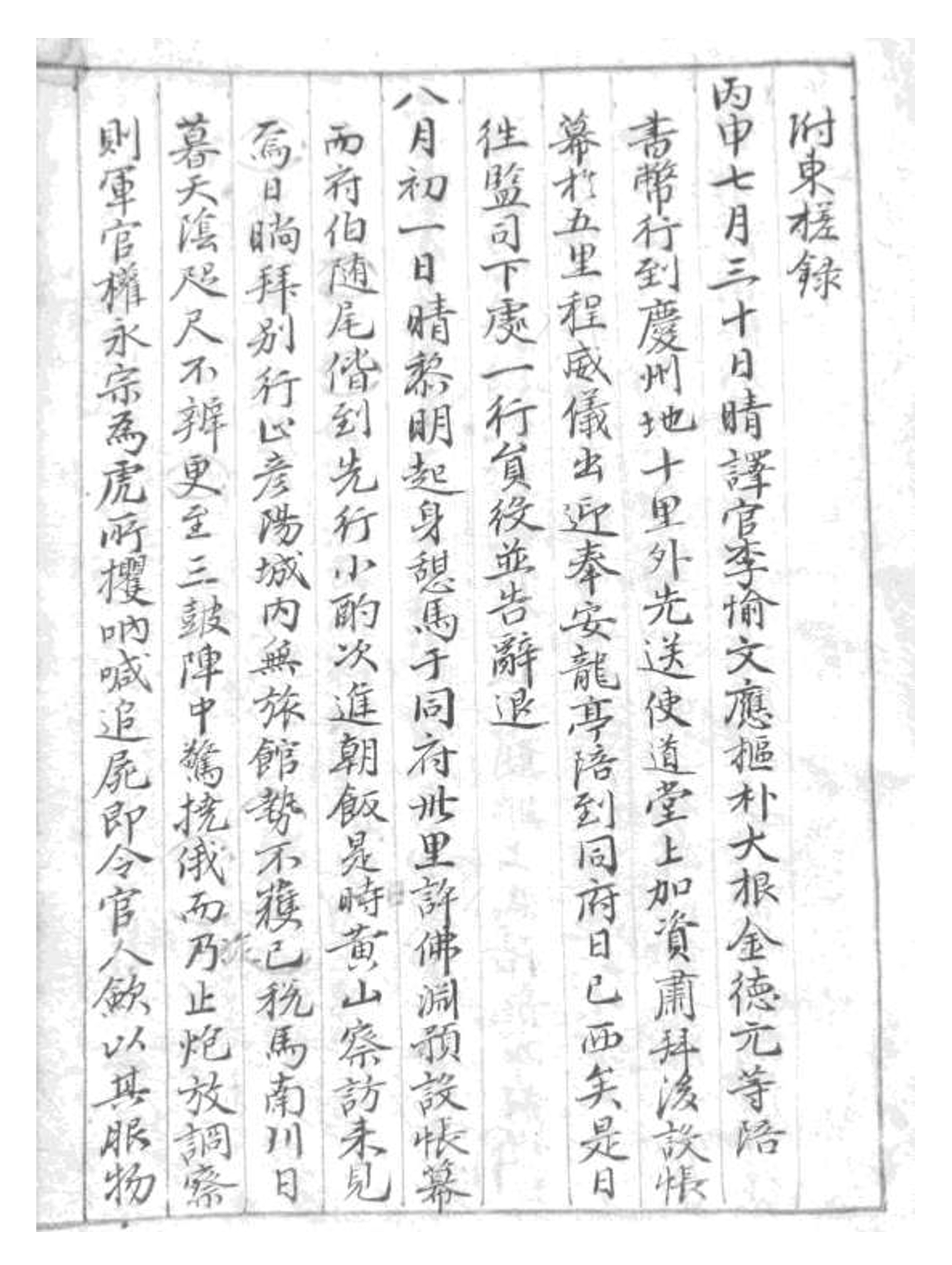

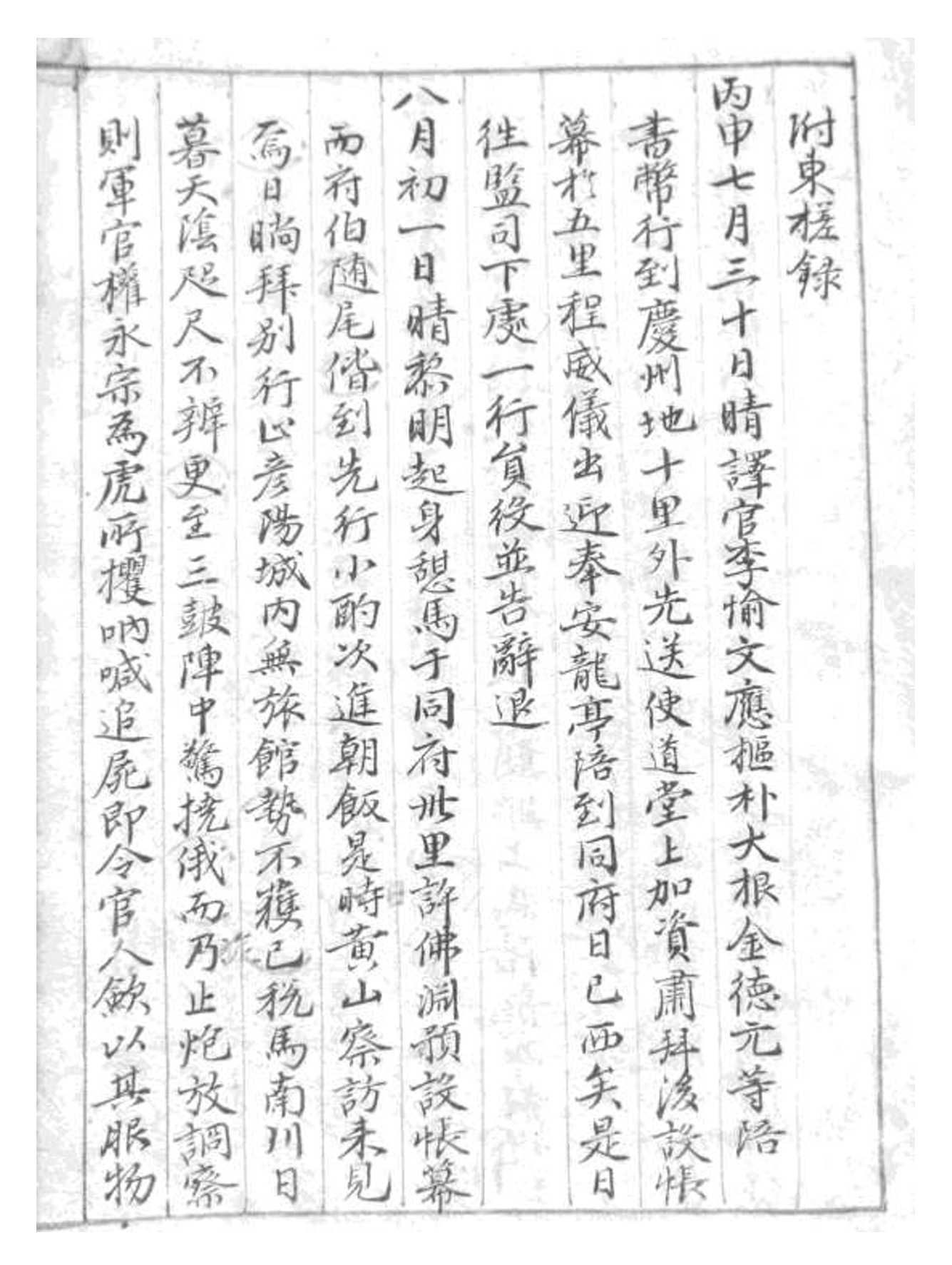

The diary that describes Hwang’s experiences on his voyage is known as

Ilbon Wanghwan ilgi śó•śú¨ŚĺÄťāĄśó•Ť®ė (Diary of a Journey to Japan and Back). There are two known surviving copies of

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi, both of which are manuscripts.

13 Unlike the diary of the Deputy Ambassador, the text appears to be written by Hwang Shin himself.

14 Given the fame Hwang enjoyed for his literary talents, it would have been odd if he had let someone else write on his behalf.

Hwang‚Äôs writing was no idle hobby, but had immediate political purpose. Hwang faced political attack almost as soon as he returned to court. His enemies objected to the king rewarding him, when in their eyes he had failed in his mission. One of the repeated indictments against him read as follows: ‚ÄúThe old villain [i.e. Hideyoshi] is fierce and wily, and repeatedly spoke rashly. [Hwang] Shin did not manage to speak once to reprimand him, only listening to his threats and returning cowed.‚ÄĚ ŤÄĀŤ≥äŚÖáÁč° ŚČćŚĺĆÁéáŤĺ≠šłćšłÄŤÄĆŤ∂≥ śĄľśõĺšłćŤÉĹŚáļšłÄŤ®ÄŤÄĆŤ©įšĻč ŚĒĮŤĀĹśĀźŤĄÖšĻčŤ®Ä šŅõť¶ĖšĽ•ś≠ł.

15 These attacks were indicative of the kind of factional fighting that had cost Hwang his office just a few years earlier, and the threat to his promising career may have felt real.

16

In the diary, Hwang is not able to avoid the fact that he did not have a single chance to speak or write to Hideyoshi or indeed play any active role in the unfolding events. Instead, the diarist employs set-piece dialogues, speeches, and poetics to counter possible criticisms and present Hwang in a most attractive light. The Chief Ambassador of Ilbon wanghwan ilgi is fearless in the face of danger, dutiful to the point of a fault, and respected as courageous even by his enemies. Apart from recording the sequence of events and the culture and society of Japan, this positive self-portrayal is undoubtedly the primary function of the diary. This of course means we must read Hwang’s diary with a critical eye, but provided we appreciate its limitations, Ilbon wanghwan ilgi is a valuable historical source for the breakdown of the 1596 peace negotiations.

The Diary of Pak Hongjang

As a second diary of the same journey, Tong sa rok śĚĪśßéťĆĄ (Record of an Eastern Voyage), offers a rare chance to compare and contrast with the account of events given in Ilbon wanghwan ilgi.

Tong sa rok ostensibly records the journey of Pak Hongjang, but other than whom he met and where he slept, it gives no personal information about the Deputy Ambassador.

17 It therefore diverges considerably from the self-promoting

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi in its purpose of composition. There is only one known extant copy of

Tong sa rok, which is included with other works connected to Pak, collected under the title

Kwan‚Äôgam nok ŤßÄśĄüťĆĄ (Record of That Seen and Sensed), held in the Nagoya Castle Museum (by the site of the original castle from where Hideyoshi launched the 1592 invasion).

18 A comment by Pak’s relative included in this copy of the diary perfectly sums up how the diary contrasts with that of Hwang Shin:

The preceding Tong sa rok is the diary of my great uncle, the envoy, from the time he went to sea. Now it is not known who the author is, but judging from the authorial voice, it must have been the clerk in charge of records under His Excellency’s command.

As far as clear or clouded skies, wind or rain, distances and accommodation are concerned, they are recorded in no little detail. But that it fails to record His Excellency’s words and expressions as he was negotiating and planning, and how he awed those in the same boat and of a different race, is most lamentable.

19

ŚŹ≥śĚĪśßéťĆĄšłÄŚłô ŤŅļŚ•ČšĹŅśõ匏ĒÁ•ĖŤą™śĶ∑śôāśó•Ť®ėšĻü šĽäšłćÁü•ŚÖ∂ŚáļśĖľŤ™įśČč ŤÄĆŤ©≥ŚÖ∂Ť™ěŚčĘ ŚŅÖŚ•ČšĹŅŚÖ¨Áģ°šłčśéĆŚŹ≤ŤÄÖśČĝƥšĻü ŚÖ∂ťôįťôŝʮťõ®ťĀďťáĆś¨°Ťąć Ť®ėšĻčťĚ욳捩≥ ŤÄĆŚ•ČšĹŅŚÖ¨ŤęģŤęŹŤ©ĘŤ¨ÄšĻčťĖď Ť®ÄŚčēŚģĻŤČ≤šĻčťöõ śúČŤ∂≥šĽ•ťéģśá匟ƍąüÁĖäŤģčÁēįť°ěŤÄÖ ŚŹćšłćśöጏäÁĄČ ÁĒöŚŹĮśÉúšĻü

Judging by the generational difference, this commentator was probably writing in the seventeenth century. He observes the feature that most distinguishes

Tong sa rok from

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi: it records detail, but has little or nothing to say about the greatness of Deputy Ambassador Pak.

Tong sa rok is often more detailed in describing the environment. For example, both accounts describe the island of Tsushima Śį杶¨ as in a very poor state, but

Tong sa rok goes into more depth, explaining the economic reasons behind this, and further describing the administrative districts, lifestyles of the inhabitants, and so on.

20 Yet the ambassadors Hwang and Pak are only mentioned in terms of where they stayed or who they met; there are no dialogues, heroics or men of charisma. In this way,

Tong sa rok acts as the perfect foil for Hwang’s

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi. For example,

Tong sa rok‚Äôs more straightforward style reveals the extent to which Hwang was editing for the purposes of ‚Äúimage management‚ÄĚ when Hwang‚Äôs rigid ‚Äúgoing to pay respect‚ÄĚ to a Chinese official is revealed in

Tong sa rok to have been an evening spent drinking and making merry together (all merry-making is self-censored from Hwang’s account).

21 It is also revealing that the type of personality of which Pak’s descendant laments the absence, is precisely that embellished in Hwang Shin’s diary: words and actions that awe friends and foes alike

.

Journey to Japan

Hwang Shin‚Äôs self-promotion begins immediately after the ambassadors set sail at the beginning of the eighth month of 1596, setting the tone for his whole account of the mission. In waters between Tsushima and Ikinoshima Ś£ĻŚ≤źŚ≥∂, the ships were caught in a violent storm. According to Ilbon wanghwan ilgi, under the force of the wind the ropes on the sails were ready to break and the ship leaned almost to the point of capsizing. The ship leapt and fell like a galloping horse. All aboard were terrified. All, that is, except Chief Ambassador Hwang. In the midst of spray falling on the deck ‚Äúlike rain,‚ÄĚ Hwang Shin composed an oath to the sea: a prayer to the spirit of the sea in a style of Classical Chinese that makes use of parallel couplets. Soon after he had finished it and tossed it into the water the wind is reported to have subsided.

The text of the oath read as follows:

I, Ambassador of ChosŇŹn, dare to make a declaration to the Spirit of the Eastern Sea: In the dog and tiger-filled thickets, I served two years; above the sea dragon‚Äôs lair I now sail in the eighth month‚Äôs raft. That I am willing to give my life in duty, I bow and pledge. For I have been born into times of turmoil, and as one sworn to the service of the state, trials and tribulations, many have I tasted. Yet be it in the provinces or the barbarian lands, only the loyal and sincere are fit to serve. Sure in my unfailing loyalty, I can vow by the heavens without shame. While carrying out my four-thousand-mile mission, I have not once dared wince from hardship; my thirty years of self-cultivation, may they serve me this day. [For] what are the unsettled affairs of the king are also the rightful duty of his servant.

Spreading the sails I make for the distant Land of the Sun. If it would secure the royal house and benefit the country, then I will not refuse even death; if I were to disgrace the mission entrusted me and fall into dishonour, then of what good would be life?

May his Divine Holiness look down and bear witness to my sincerity; and may these words be not false. Heaven is all knowing; should I be lax in but one thought, let the spirits strike me down. All this I submit in reverence.

22

śúĚťģģťÄöšŅ°šĹŅśüź śēĘ[śė≠*]ŚĎäśĖľśĚĪśĶ∑šĻčÁ•ě šľŹšĽ•ŤĪļŤô錏ʚł≠ śóĘśĆĀšļĆŚĻīšĻčÁĮÄ ŤõüťĺćÁ™üšłä ŚŹąšĻėŚÖęśúąšĻčśßé śćźť©Ö[ŤĽÄ]śėĮÁĒė Á®Ĺť¶ĖŤá™Ť™ď šľŹŚŅĶśüźťĀ≠śôāśĚŅÁõ™ Ť®ĪŚúčť©Öť¶≥ ťõĖťö™ťėĽŤČĪťõ£ ŚāôŚėóšĻčÁü£ ÁĄ∂Ś∑ěťáĆŤ†ĽŤ≤ä ŚŹĮŤ°ĆšĻéŚďČ Ť≥īśúČŚŅ†ŤĶ§šĻčšłćśłĚ ŚŹĮŤ≥™šłäŤíľŤÄĆÁĄ°Ś™Ņ ŚõõŚćÉťáĆŤ°ĆŚĹĻ šĹēśēĘšłÄśĮęśÜöŚčě šłČŚćĀŚĻīŚ∑•Ś§ę ś≠£ŚģúšĽäśó•ŚĺóŚäõ ŚõļÁéčŚģ§šĻčťĚ°[ťĻĹ] śäĎŤá£ŤĀ∑šĻčÁē∂ÁĄ∂ ÁõīśéõťĘ®ŚłÜ ťĀôśĆáśó•Śüü ŤĆ挏ĮŚģČÁ§ĺŚą©Śúč ś≠ĽšłĒšłćŤĺ≠ Ś¶āšĹŅŤĺĪŚĎĹŚ§ĪŤļę ÁĒüšļ¶šĹēÁõä šľŹť°ėťĚąŤĀĖšŅĮťĎíŚŅĪŤ™† ŚĻłśĖĮŤ®ÄšĻ蚳捙£ Ś§©śúČÁü•šĻü ŚÄėšłÄŚŅĶšĻčśąĖśÄ† Á•ěŚÖ∂śģõšĻč Ť¨ĻŚĎä

23

It is perhaps not surprising that while relating this dramatic event the diary fails to mention that Hwang in fact suffered badly from sea sickness ‚Äď it is questionable whether he was upright let alone composing poetic couplets.

24 Hwang’s grand pronouncement, sworn to Heaven and proved authentic by the weather’s response, is a statement of both Hwang’s courage and sense of duty. Within the diary, it sets the scene for Hwang to face the dangers of the mission; beyond the diary, it declares him fit for high office.

The difference in style between

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi and

Tong sa rok is vividly demonstrated by the matter-of-fact entry of the latter for the same day‚Äôs voyage: ‚ÄúSet sail at dawn. Arrived at Ikinoshima at dusk.‚ÄĚ

25

Hwang‚Äôs composition was not just a literary flourish contained within the diary: the text of ‚ÄúOath to the Sea,‚ÄĚ along with the dramatic story of its acceptance by the spirits of the sea, spread quickly around ChosŇŹn on his return and caused a stir.

26 Later histories also continued to quote it.

27 This was a self-confident declaration from a literary and political rising star.

Osaka and Hideyoshi’s wrath

Despite sailing all the way to the adjacent port of Sakai, Hwang and Pak never actually reached Osaka, and never managed to meet the infamous Hideyoshi, who had ensconced himself there. On the 18th day of the intercalary eighth month, they sailed into the harbour at Sakai (which today is encompassed in the Osaka area). It was a sunny day, and a fanfare played as the two Ming ambassadors and a Japanese delegation led by Yukinaga came to meet the ships. The pomp and ceremony was not for the ChosŇŹn ambassadors, but for the Ming Imperial edict which they had been escorting.

28

Hwang Shin describes in detail how, after he and Pak Hongjang had performed the appropriate ritual bowing to the two Ming ambassadors at Yang Fangheng‚Äôs accommodation, they insisted on following Shen Weijing to his accommodation to again bow to him there, despite Shen saying this was unnecessary. This show of conscientious propriety is typical of Hwang‚Äôs account, and sits in contrast with Pak‚Äôs diary, which omits the later visit to Shen‚Äôs accommodation ‚Äď leaving us to doubt whether it ever took place.

29 The author of

Tong sa rok is more interested in describing his environment; he was clearly impressed by what he saw on arriving in Sakai:

Tall buildings and planked houses extend wall-to-wall for more than ten

ri [2.5 miles], totalling almost ten thousand. Due to the previous earthquake, some among them were damaged and have not been repaired. Apparently countless people and animals died. In the market the goods shine and glitter, catching the eye; it cannot be known how many millions of different kinds there are.

30

ťęėťĖ£śĚŅŚĪčťÄ£Áį∑ŚćĀť§ėťáĆ ŚĻĺŤá≥Ťź¨Śģ∂ śõĺŚõ†Śúįťúá ťĖďśúČť†ĻŚ£ěśú™šŅģŤÄÖ Ś£ďś≠ĽšļļÁēúÁĄ°ÁģóšļĎÁü£ Śłāšł≠ÁČ©ŤČ≤ÁÖߍÄÄŚ•™Áõģ šłćÁü•ŚÖ∂ŚĻĺŚćÉŤź¨Á®ģšĻü

The diarist here does not hide his wonder at the spectacle of flourishing trade they encounter on arrival in Japan.

It was due to the devastating earthquake shortly beforehand that Fushimi šľŹŤ¶č Castle, where Hideyoshi had planned to receive the ambassadors, could no longer be used. This was a devastating earthquake with its epicentre very near the castle, and news of it even reached people in ChosŇŹn.

31 Nevertheless, soon after their arrival they heard that Hideyoshi felt this need not delay his meeting with them:

Yukinaga and the others returned from the capital [Kyoto] and reported: ‚ÄėThe Kampaku [Hideyoshi] is ecstatic to hear that the ambassadors have arrived. He will not wait for another hall to be built, and will meet with the Celestial Ambassadors and the [ChosŇŹn] ambassadors on the 2nd day of the ninth month.

32

Ť°Ćťē∑Á≠Č ŚõěŤá™šļ¨ŚüéšĺÜŚ†Īśõį ťóúÁôĹŤĀěšŅ°šĹŅšĻčšĺÜ ś•ĶÁĒöŚĖúśāÖ šłćŚĺÖŚą•Ááüť§®Śģá Áē∂śĖľšĻĚśúąŚąĚšļĆśúÉŤ¶čŚ§©šĹŅŚŹäšŅ°šĹŅ šļĎšļĎ

While we may suppose that some of Hideyoshi’s exuberance was the exaggeration of the messengers, the proposed meeting is indeed arranged for only a week later, and news came of Hideyoshi having returned to Osaka within just a few days.

33 Yet, according to

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi, the very next day after he arrived in Osaka (29th), his attitude towards ChosŇŹn and its officials was being reported in very different terms:

[Yanagawa] Shigenobu summoned Pak TaegŇ≠n [the interpreter] and told him: ‚Äėjust now Yukinaga, [Terazawa Hirotaka], and the others returned from Hideyoshi‚Äôs quarters saying that the Kampaku had said:

‚ÄúIn the beginning I wanted passage to China and ChosŇŹn would not act as an intermediary. Then after it had come to armed conflict, Shen [Weijing] wanted to reconcile the two countries but ChosŇŹn remonstrated to the Ming in the strongest terms that it must not be allowed. ChosŇŹn consistently spoke against Shen [Weijing], thinking him to be in league with Japan. The departure of Celestial Ambassador Li [Zongcheng] also goes back to ChosŇŹn‚Äôs scaremongering. Once the ambassadors had crossed the sea, ChosŇŹn was unwilling to send officials with them, taking their time and only now arriving. Furthermore they did not send a prince. In every matter they have slighted me severely. I cannot allow an audience to the envoys who have come. I will first meet with the Celestial Ambassadors, and keep the ChosŇŹn ambassadors here. I will only grant them an audience after writing to the Ministry of War and investigating their reasons for being late.‚ÄĚ

34

ŚĻ≥Ť™ŅšŅ°śčõśúīŚ§ßś†ĻŤ¨āśõį Ść≥ŚąĽŤ°Ćťē∑ś≠£śąźŤá™ťóúšľĮŤôēŚõěťāĄŤ®ÄťóúšľĮśõį Áē∂ŚąĚśąĎś¨≤ťÄöšł≠ŚúčŤÄĆśúĚťģģťĀéšłćÁāļťÄöśÉÖ ŚŹäŤáīŚčēŚÖĶšĻčŚĺĆ ś≤ąťĀäśď䜨≤Ť™ŅśąĘŚÖ©Śúč ŤÄĆśúĚťģģšłäśú¨ ś•Ķťô≥ŚÖ∂šłćŚŹĮ šłĒšĽ•ś≤ąťĀäśďäÁāļŤąáśó•śú¨ŚźĆŚŅÉ śĮŹśĮŹśÉ°šĻč śĚ錧©šĹŅšĻčŚáļŚéĽ šļ¶ŚõěśúĚťģģšĻčšļļśĀźŚčē ŚÜäšĹŅśóĘśł°śĶ∑ ŤÄĆśúĚťģģšłćŤāĮŚ∑ģŚģėŤ∑üšĺÜ šĽäŚßčÁ∑©Á∑©šĺÜŚąį šłĒšłćťĀ£ÁéčŚ≠źšĺÜ šļčšļ荾ēśąĎÁĒöÁü£ šĽäšłćŚŹĮŤ®ĪŤ¶čšĺÜšĹŅ śąĎÁē∂ŚÖąŤ¶čŚ§©šĹŅ ŚĺĆŚßĎÁēôśúĚťģģšĹŅŤá£ Á®üŚłĖŚÖĶťÉ® ŚĮ©ŚÖ∂šĺÜťĀ≤šĻčśēÖ ÁĄ∂ŚĺĆśĖĻÁāļŤ®ĪŤ¶čšļĎ

It is not clear whether Hideyoshi changed his mind over the intervening days, or whether the ChosŇŹn ambassadors‚Äô hosts had simply withheld news of Hideyoshi‚Äôs displeasure until this point.

35 We must be highly cautious in reading the reported statements of Yukinaga and the group around him, as we know that their diplomatic efforts had always been built on filtering and manipulation of messages. Some of the reasoning they relay here may well be their own. Yet, the core theme here of Hideyoshi feeling he had not been sufficiently respected is credible, fitting with what we know of Hideyoshi and the course of events.

The background to this cool reception for the ChosŇŹn ambassadors was that Hideyoshi had long believed ChosŇŹn to be a vassal of Japan.

36 The SŇć Śģó house of Tsushima and others had conspired to maintain a pretence of ChosŇŹn submission, in an attempt to avoid disruption of the trade with ChosŇŹn upon which Tsushima‚Äôs economy depended. From 1592, ChosŇŹn had of course attempted to resist the Japanese army as it headed for China, making the ChosŇŹn king a rebellious vassal in Hideyoshi‚Äôs eyes. Hideyoshi was a man who had risen to dominance out of the Japanese civil war by effectively utilizing threat and reward to win vows of allegiance from his would-be rivals; disobedience from vassals was not something he could afford to countenance, nor was he so inclined.

37 Therefore, while Hideyoshi appears to have been eager for recognition from the Ming emperor as something which bolstered his prestige, ChosŇŹn‚Äôs continued ‚Äėinsubordination‚Äô incensed him.

38

Yanagawa Shigenobu śü≥Ś∑ĚŤ™ŅšŅ° (d. 1605), the messenger cited above, was part of the group around Yukinaga and belonged to the house of SŇć of Tsushima, which so relied on trade with ChosŇŹn. It was in this group‚Äôs interests to placate Hideyoshi regarding ChosŇŹn and complete the peace settlement. They had evidently believed it was possible to satisfy him with an emissary, but Hideyoshi seems to have become more and more angry at ChosŇŹn‚Äôs apparently disrespectful behaviour.

39 This caused a problem, as from the Ming-ChosŇŹn standpoint, securing the withdrawal of Japanese troops from ChosŇŹn had originally been both the goal and prerequisite of Hideyoshi‚Äôs investiture; as Shigenobu put it, ‚Äúthe Celestial Court investing the Kampaku is not for the Kampaku‚Äôs sake, but solely to save ChosŇŹn.‚ÄĚ

40 While angry with ChosŇŹn, Hideyoshi was unlikely to agree to withdraw and ‚Äúlet them off‚ÄĚ without punishment, yet Ming ambassadors Yang and Shen could not afford to leave without securing a withdrawal.

The final explosion of this tense situation is recorded in Hwang‚Äôs diary as coming several days after Hideyoshi accepted investiture as ‚ÄúKing of Japan‚ÄĚ from the Ming ambassadors. Only after much worrying and urging on the parts of Yukinaga‚Äôs group and the ChosŇŹn ambassadors did Shen Weijing finally broach withdrawal of Japanese forces from ChosŇŹn with Hideyoshi. Fearing a face to face encounter, Shen wrote a letter, which Yukinaga and others took to him in Osaka on the 6

th day of the ninth month.

41 According to this account, it was Hideyoshi’s fury on receiving this letter that ended official negotiations, and doomed the region to another year of bloody warfare.

Hwang and Pak received the ominous news in the middle of the night, relayed once more by Shigenobu.

42 The words Hideyoshi is quoted as having said in his burst of fury at this time, through Hwang‚Äôs reporting, came to be known far and wide in both ChosŇŹn and Ming China. Hwang quotes Shigenobu as having said:

The Kampaku became furious, saying: ‚ÄúAs for the Celestial Court, given that it has already sent envoys to invest [me], I tolerate it for the time being. Yet ChosŇŹn is as disrespectful as this! There can be no peace now. How can we discuss withdrawal just when I am in a mind to fight? The Celestial Ambassadors also need not tarry long. Have them set sail tomorrow. You can also order the ChosŇŹn ambassadors to leave. Meanwhile I will start mobilizing forces to go to ChosŇŹn this winter.‚ÄĚ

He has also apparently summoned Kiyomasa to discuss plans. If Kiyomasa has his way, then things will go badly. Yukinaga and all of us will be dead in no time.

43

ťóúšľĮŚ§ßśÄíśõį Ś§©śúĚŚČáśóĘŚ∑≤ťĀ£šĹŅŚÜäŚįĀ śąĎŚßĎŚŅćŤÄź ŤÄĆśúĚťģģŚČáÁĄ°Á¶ģŤá≥ś≠§ šĽäšłćŚŹĮŤ®ĪŚíĆ śąĎśĖĻŚÜ捶ĀŚĽĚśģļ ś≥ĀŚŹĮŤ≠įśí§šĻčšļčšĻé Ś§©šĹŅšļ¶šłćť†ąšĻÖÁēô śėéśó•šĹŅŤę蚳䍹Ļ śúĚťģģšĹŅŤá£šļ¶šĽ§ŚáļŚéĽŚŹĮšĻü śąĎÁē∂šłÄťĚĘŤ™ŅŚÖĶ Ť∂ĀšĽäŚÜ¨ŚĺÄśúĚťģģšļĎšļĎ šłĒŤĀěŚ∑≤ŚŹ¨śłÖś≠£šĺÜŤ®ąšļč śłÖś≠£ŚĺóŚŅó ŚČášļčŚįášłćśł¨ Ť°Ćťē∑ŤąáśąĎŤľ©ś≠ĽÁĄ°śó•Áü£

The news that Hideyoshi would launch another invasion confirmed the worst fears of the ChosŇŹn ambassadors, and seems to have devastated Shigenobu and the other Japanese working for peace, with Yukinaga reportedly considering suicide upon seeing four years of tireless effort crumble before his eyes.

44 Yukinaga likely also feared for his life: the Portuguese observer Luis Frois (1532-1597) wrote that Hideyoshi was positively apoplectic with rage.

45

With Hideyoshi demanding the immediate departure of both Ming and ChosŇŹn ambassadors, both groups had no choice but to make preparations for a swift return home. Not delivering the letter from King SŇŹnjo that was entrusted to him meant Hwang could be accused of failing in his mission.

46 In

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi we therefore find dialogues with both Yang and Shen, where the two ChosŇŹn ambassadors explain their predicament and express their wish to die, only to have their position comprehensively defended by the Chinese officials.

47

Return from Japan

Hwang and Pak would have set off from Sakai with fearful and heavy hearts. Not only had they failed in their mission, but another devastating invasion of their country loomed. On top of this, Shen Weijing and their Japanese escort attempted to prevent them from sending word of what had happened ahead to ChosŇŹn. The Ming ambassadors had immediately dashed off a report claiming a kowtowing Hideyoshi had gratefully accepted his investiture, and concealing his subsequent wrath

48 While they would have been anxious, waiting for an opportunity to send their urgent report, the return journey was a chance for the two diarists to observe the different places and people which they were once again passing. In both diaries there are fascinating glimpses of their impressions.

Attitudes towards Koreans in Japan

When the ChosŇŹn ships were due to depart on the 9th day of the ninth month, Hwang records how many of the Koreans who had been captured and taken to the islands as slaves crowded around the vessels, watching their last hope of return disappear:

Earlier, when the ambassadors first arrived at Sakai harbour, men and women of our country who had been abducted all rushed to come and see them … All the Japanese generals also regularly sent boys they had abducted to see the ambassadors, always saying that once the negotiations were completed, they could go back with the ambassadors. When they heard that the ambassadors were readying to depart, some gave money for the journey and sent [the boys]; gradually they came to the ambassadors’ lodgings, awaiting boarding of the ships.

At this point, each of the Wae masters heard that the peace process had failed, and that there would be fighting again. They then went back on their word, and all those that had come to the lodgings were recalled. Only twenty or so men and women, including the daughter of Kim Yongch‚ÄôŇŹn, came together on the luggage ship.

When the ambassadors were boarding the ships, countless men and women of our country followed howling and weeping. There was not a dry eye among the whole company. The ships did not depart, and [we] slept on board.

49

ŚÖąśėĮ ťÄöšŅ°šĹŅŚąĚŚąįÁēĆśŅĪ śąĎŚúčŤĘęśďĄÁĒ∑Ś©¶ Áą≠šĺÜŤ¨ĀŤ¶č ‚ĶŚźĄŚÄ≠Śįá šļ¶śôāťĀ£śČĜ樓ÖíÁę•Ťľ©šĺÜŤ¨Ā śĮŹŤ®ÄŚíĆšļčŤč•ŚģĆ ŚČáÁē∂ťö®šĹŅŤá£ś≠ł ŚŹäŤĀěťÄöšŅ°šĹŅŚįáŚēüÁ®č śąĖśúČÁĶ¶Ť°ĆŤ≥áŤÄĆťĀ£šĻčŤÄÖ Á®ćÁ®ćšĺÜŚąįťÄöšŅ°šĹŅśČÄŚĮď šĽ•ŚĺÖšłäŤąĻšĻčśúü Ťá≥śėĮ ŚźĄŚÖ∂šłĽŚÄ≠Á≠Č ŤĀěŚíĆšļčšłćśąź Áē∂ŚÜ挼̜ģļ ťĀāśĒĻŚČćŤ®Ä Ś∑≤ŚąįŚĮďśČÄŤÄÖ šļ¶ÁöÜŤĘꌏ¨ŚéĽ ŚĒĮťáĎśįłŚ∑ĚŚ•≥Ś≠źŚŹäÁĒ∑Ś©¶šļĆŚćĀť§ėšļļ ŚĀēŤľČŚćúÁČ©ŤąĻ ťÄöšŅ°šĹŅšłäŤąĻšĻčťöõ śąĎŚúčÁĒ∑Ś©¶ ŤŅĹťÄĀŤôüś≥£ŤÄÖšłćÁü•ŚÖ∂ŚĻĺšļļ šłÄŤ°ĆŤéęšłćťÖłťľĽ šłćÁāļÁôľŤąĻ šĽćŚģŅŤąĻšłä

Tong sa rok gives only a minimalist account of the company’s movements for this period, having given more detail on meetings with Koreans during the outward journey. When the party arrived at Nagoya, Tong sa rok records that they met abducted Koreans in person:

Men and women who had been forcibly taken, longing for home, came from near and far in their hundreds and thousands. But the villains kept them imprisoned without release. Some of them would hear my voice and come crying; it was so terrible one could not meet eyes with them. Those that had been taken captive as children were fluent in the barbarian tongue, and could not understand our language. It is truly tragic.

50

ŤĘęśź∂ÁĒ∑Ś©¶ śá∑śąÄť¶Ėšłė Ťá™ťĀ†ŤŅĎšĺÜťõÜŤÄÖ ŚćÉÁôĺÁāļÁĺ§ ŤÄĆŚÖáŚĺíÁ¶ĀśäĎ ŚĻĹŚõöšłćśĒĺ śąĖśúČŤĀ윹ύĀ≤ťü≥šĺÜŚď≠ŤÄÖ śÖėšłćŚŅćÁõłŤ¶Ė ŚÖíśôāŤ¶čšŅėŤÄÖ ŚČጏ£ÁÜüťīÉŤąĆ šłćŤß£śąĎŤ™ě ŤČĮŚŹĮśāľś≠éšĻü

Both diarists are plainly moved by the plight of those forced into slavery in an unknown land. It is interesting that the

Tong sa rok diarist seems to have found the cruelty of these Koreans being kept far from their homeland more upsetting than their being kept in slavery ‚Äď perhaps this is because slavery was an integral part of the ChosŇŹn social system. His sympathy also seems to be for all the people from ChosŇŹn: neither diarist differentiates between those of noble and lowly birth, as would be common in a domestic context.

51 The

Tong sa rok diarist evidently feels it is particularly tragic that children born in ChosŇŹn should not understand ‚Äúour language,‚ÄĚ but grow up speaking a foreign tongue.

As a footnote to these sad scenes, a few days later one of the interpreters with the embassy is recorded as paying for the release of a slave. This was not a commoner, however, but the son of a minor official.

52 Later, when they returned and Hwang Shin was called for an interview with King SŇŹnjo, the king specifically asked about ‚Äúour people‚ÄĚ śąĎśįĎ in Japan, to which Hwang responded disparagingly that they all speak Japanese and have forgotten ChosŇŹn.

53 This obvious exaggeration (it had been only four years since the start of the war and the abductions) seems to indicate he somehow blamed them for their ‚Äúbetrayal‚ÄĚ of their country, but again highlights the perceived importance of language as symbolic of Korean identity.

In his diary, Hwang records how he in fact agreed to bring a captured boy back with him to ChosŇŹn. This boy had been kept in the house of Terazawa HirotakaŚĮļśĺ§ŚĽ£ťęė (1563-1633), but was so homesick that Hirotaka took pity on him and asked that Hwang search for his family. He added that if the boy‚Äôs family had not survived, then he would be very grateful if Hwang could return the boy to him, so that he would not be left homeless.

54 By recording this incident Hwang presents a far more complex image of the Japanese than most writings at the time. Here was a Japanese commander ‚Äď who were commonly vilified as savage and cunning beasts ‚Äď showing compassion and generosity of heart. Hwang had spent several months in close quarters with Japanese people who were working to save ChosŇŹn from further disaster (even if these were the same men who had been in the vanguard of the invasion). It is therefore not surprising that the perspective Hwang shares with his fellow countrymen is very different from the image of violent and unpredictable savages we see in the writing of Oh HŇ≠imun, who never actually met a Japanese person.

Japan and the Japanese

The final part of Ilbon wanghwan ilgi is actually dedicated to explaining the foreign land of Japan and its people to the reader, so makes particularly interesting reading. It begins as follows:

To speak as a whole, the country of the Wae is slightly greater in area than our country, but it lacks the solidity of famous mountains or great rivers. Its scenery and produce are all inferior to our country. There is a mountain known as Fuji in the east of the country, which is most acclaimed as a great mountain, but otherwise there is no scenery or outstanding beauty worthy of mention.

55

Ś§ßśß© ŚÄ≠ŚúčŚĻÖŚď°Á®ćŚĽ£śĖľśąĎŚúč ŤÄĆÁĄ°ŚźćŚĪĪŚ§ßŚ∑ĚšĻčŚõļ ťĘ®ŚúüÁČ©ÁĒĘšŅĪšłćŚŹäśąĎŚúč śúČśõįŚĮĆŚ£ęŚĪĪ Śú®ŚúčšĻčśĚĪ śúÄŤôüŚ§ßŚĪĪ ŤÄĆŚą•ÁĄ°ŚĹĘŚčĚšĹ≥ťļóšĻ茏ĮŤßÄ

This uncomplimentary appraisal sets the tone for much of Hwang’s account; for example, his assessment of Japan’s administration:

They have roughly imitated the Tang system but in reality officials are not in charge of matters connected to their post. For example, Shigenobu claims to be Deputy of the Secretariat (what is known as the Librarian), but he is illiterate. [KatŇć] Kiyomasa claims to be Master of Accounts, but has never dealt with money or grain. It seems they merely use empty titles.

The people consist of soldiers, farmers, artisans, merchants, and monks, but only monks and those of noble families can read. As for the others, even if they are military or civilian officials, they cannot recognize a single character.

56

ŚģėÁēßśĒĺ[ŚÄ£]ŚĒźŚą∂ÁāļšĻčŤÄĆŚÖ∂ŚĮ¶Śą•ÁĄ°śČÄÁģ°ŤĀ∑šļč Ś¶āŤ™ŅšŅ°Ťá™Á®ĪÁßėśõłŚįĎÁõ£ śČÄŤ¨āŚúĖśõł ŤÄĆÁõģšłćÁü•śõł ŚĻ≥śłÖś≠£Ťá™Á®ĪšłĽŤ®ą ŤÄĆŚąĚšłćÁģ°ťĆĘÁ©Ä Ťď茏™ÁĒ®ŤôõŚĺ°[ťäú]šĻü ŚÖ∂śįĎśúČŚÖĶŤĺ≤Ś∑•ŚēÜŚÉß ŤÄĆŚĒĮŚÉߌŹäŚÖ¨śóŹśúČŤß£śĖáŚ≠óŤÄÖ ŚÖ∂ť§ėŚČáťõĖŚįáŚģėŤľ© šļ¶šłćŤ≠ėšłÄŚ≠ó

In claiming that ‚Äúthey cannot recognise a single character‚ÄĚ Hwang is equating literacy with ability to read Classical Chinese: earlier diary entries show Shigenobu and others engaging in written correspondence, but presumably in Japanese. In judging the Japanese by their ability in Classical Chinese, or lack thereof, Hwang was joining with all other contemporary Chinese and Korean observers who wrote on the subject; Kang Hang Śßúś≤Ü (1567-1618) and Xu Yihou Ť®ĪŚĄÄŚĺĆ, for example, enjoyed ridiculing the Japanese on this point.

57 Hwang Shin was of course no less than the

changwŇŹn: the man who had come out top of a civil service examination system that linked knowledge of the Chinese classics to ability in government. It is hardly surprising that he finds it strange that men of official rank in Japan have no such education. Still, whether it be Hwang or Xu Yihou, we see that for educated Chinese and Korean observers this perceived lack of cultural knowledge formed an important part of their impression of the Japanese.

Hwang Shin is not critical of everything Japanese, however. Continuing onto social classes, he writes:

Soldiers receive a salary from the government. Merchants are the most wealthy, but as their profits are twice that of others, their tax is slightly higher. State expenses both great and small are all put upon the merchants. In the case of farmers, half of the produce of their fields is collected, but there are no other taxes or corvée. For transport and construction work a wage is given,

so the burden does not reach the common people.

58

ŚÖĶŚČáŚĖęŚģėÁ≥ß ŚēÜšļļśúÄŚĮĆŚĮ¶ ŤÄĆšĽ•ŚÖ∂Śą©ŚÄćśēÖÁ®ÖÁ®ćťáć ŚúčśúČŚ§ßŚįŹŤ≤ĽÁĒ® ÁöÜŤ≤¨śĖľŚēÜšļļ Ťĺ≤śįĎŚČáśĮŹÁĒįśĒ∂ŚÖ∂Śćä ś≠§Ś§ĖÁĄ°ŚģÉŤ≥¶ŚĹĻ śľēŤĹČŚ∑•ŚĹĻÁöÜÁĶ¶Śā≠ŚÉĻ śēÖŚľäšłćŚŹäśįĎ

Not only is there no criticism, but in pointing out how the common people do not suffer, Hwang is actually explaining the advantages of the Japanese tax system, even discussing it as a potential model. It just so happens that Hwang was in favour of reducing corv√©e labour in ChosŇŹn, so we can suppose he was using this Japanese model to support that agenda.

59 Yet this in itself is surprising: given the beyond-the-pale position normally accorded Japan in world political, moral, and cultural hierarchy by Chinese and Korean writers at this time, Hwang Shin’s use of the Japanese system as a model is unexpected.

There were other areas of Japanese culture that the diarists reviewed positively. Both authors were impressed by the aesthetic of ‚Äúcleanliness and simplicity‚ÄĚ which they encountered. For the author of

Tong sa rok, this extended to the food they were served when they arrived in Tsushima. He describes it saying, ‚Äúas refined and immaculate as is possible.‚ÄĚ

60 High praise indeed. Hwang Shin is similarly taken aback by the decorations used at banquets:

They paint gold and silver over the fish, meat, noodles, and rice. They cut coloured material to make flowers, or they carve wood and add coloured material to make the shapes of plants and flowers, and place them around the banquet. These are in fact extremely intricate and lifelike; from four or five paces away it is not possible to distinguish whether they are real or artificial.

61

šĽ•ťáĎťäÄŚ°óť≠öŤāČťļĶť£ĮšĻčšłä ŚČ™Á∂ĶÁāļŤäĪ śąĖŚąĽśú®Śä†ŚĹ© šĽ•ťÄ†ŤäĪŤćČšĻčŚĹĘ ÁĹģŤęłÁ≠ĶŚł≠šĻčťĖď ŤÄĆś•ĶÁ≤ĺŚ∑ߝľÁúü ŚõõšļĒś≠•šĻ茧ĖŚČá šĺŅšłćŤÉĹŤĺ®ÁúüŚĀášĻü

Tong sa rok also has very high praise for the aesthetics of a newly built building in which they are at one point accommodated.

62 The author seems to imply that the size and vibrancy of the market cities they see (particularly Sakai) surpass anything he had seen elsewhere.

63

One thing that neither diarist could look on without distaste was what they deemed a lack of ye Á¶ģ ‚Äúproper behaviour‚ÄĚ connected with the teachings of Confucius and other

yu ŚĄí ‚Äúsages.‚ÄĚ They were particularly critical of Japanese custom in the areas of proper hierarchy ‚Äď to be maintained in forms of address and rituals (such as bowing) ‚Äď and propriety in sexual relations. The author of

Tong sa rok, in his overview of Tsushima, stated: ‚ÄúBuddhist Law is held in esteem, and Confucian teachings are not popular; names and roles are in disarray.‚ÄĚ

64 The otherwise consistently neutral authorial tone of

Ilbon wanghwan ilgi is broken only once, when explaining Japanese intersex relations. After describing the surprisingly overt nature of Japanese prostitution, where the prostitutes ‚Äúknow no shame,‚ÄĚ he remarks:

As for marriage, there is no taboo for siblings. If father and son lie with the same prostitute, no one will speak against them. Verily are they beasts not men.

65

Ťá≥śĖľŚęĀŚ®∂ šłćťĀŅŚ®öŚ¶Ļ Áą∂Ś≠źŚĻ∂ś∑ꚳČ®ľ šļ¶ÁĄ°ťĚěšĻčŤÄÖ ÁúüÁ¶ĹÁćłšĻü

Calling the Japanese

keumsu Á¶ĹÁćł ‚Äúbeasts‚ÄĚ was not an arbitrary insult: it was a culturally loaded term very common in contemporary writing. In the Calls to Arms circulated by volunteer commanders after the 1592 invasion, ‚Äúbeasts‚ÄĚ is used to describe the lower state of civilization to which ChosŇŹn risked falling if overrun by the Japanese.

66 The ChosŇŹn king SŇŹnjo also used ‚Äúbeasts‚ÄĚ to describe the lower level of existence to which his kingdom risked being damned.

67 In late sixteenth-century ChosŇŹn, it was the knowledge and maintenance of proper relationships, such as

puja Áą∂Ś≠ź ‚Äúfather-son‚ÄĚ and kunshin ŚźõŤá£ ‚Äúlord-vassal,‚ÄĚ that separated men from beasts. This way of thinking, based in the tradition now known as Neo-Confucianism, had gained a dominant position in ChosŇŹn society and politics following the rise of the group referred to as the

Sarim Ś£ęśěó ‚ÄúForest of Scholars‚ÄĚ faction, particularly after the accession of King SŇŹnjo (1567).

Sarim Neo-Confucianism especially emphasised the sharp dichotomies between the moral and immoral, civilized and barbarian.

68 These standards were readily applied in official ChosŇŹn writings on Japan. They were also widely propagated through children‚Äôs educational materials, such as

Tong mong sŇŹn sŇ≠p Áę•ŤíôŚÖąÁŅí (Beginning Practice for Children).

69 The concept that men and beasts were separated by morality was one of the fundamental ideas taught in another Classical Chinese primer for children,

Sohak ŚįŹŚ≠ł (Lesser Learning), which Hwang Shin himself promoted.

70 It is against this ideological background that the less regulated relations of the Japanese were so difficult to accept for Hwang Shin. The author of

Tong sa rok too, invokes similar connections when he refers to the Japanese as

yŇŹmch‚Äôi śüďťĹí ‚Äústained teeth‚ÄĚ: this was a practise of the Japanese but in historical Chinese writing was also associated with uncivilised savage tribes.

71

Given that the ideological framework in which the ChosŇŹn ambassadors had been educated drew such sharp distinctions, so readily demoting the Japanese to the level of beasts, it is surprising to find both diarists ready to praise aspects of Japanese food, craftsmanship, and even government. It seems that actual contact with the Japanese stripped away some of the habitual labelling that those who wrote without direct experience were more prone to use. Through the medium of the diaries, particularly Hwang Shin‚Äôs diary, this slightly more nuanced view of the Japanese also reached a wider audience back in ChosŇŹn.

The first piece of writing by Hwang to be received in ChosŇŹn was an urgent report he sent to the king. In it he relayed Hideyoshi‚Äôs furious rejection of Shen Weijing‚Äôs demand and that another attack was imminent. Hwang‚Äôs report caused panic in the capital, which rapidly spread throughout the country.

72 As ordinary people desperately sought refuge, the armies of Japan, ChosŇŹn and the Ming all prepared for war.

Conclusions

Even if Hwang Shin portrayed himself as fearless in the face of danger, the journey of these two ChosŇŹn ambassadors was probably one of trepidation. They were venturing right into the lion‚Äôs den, from the perspective of those back in ChosŇŹn. Even apart from being unsure what Hideyoshi would decide to do next, everything Hwang, Pak, and their company observed on their way was new and strange. As talented scholar and product of the civil-service machine, Hwang‚Äôs education could not have been more orthodox. His diary was an attempt to translate this foreign experience into language and ideas familiar to his ChosŇŹn contemporaries: those of their shared Classical Chinese education and day-to-day experience of ChosŇŹn. He was also replacing a largely unknown, unpredictable and aggressive foe with a land and people of defined territory, customs, food ‚Äď and limits. These diaries were one part in the process of mutual learning that took place during the war, in which a few people who had direct experience of another country translated that experience for the domestic audience ‚Äď an audience that otherwise knew very little about foreign countries or peoples beyond simple caricatures.

Shen Weijing, Konishi Yukinaga and the group around them were the latest generation in a long line of intermediaries between Japan and Korea and China, who had sought to use the predominating mutual ignorance between the countries to maintain peace and thus advance their own trade interests. The two diaries reveal the extent to which the ambassadors‚Äô experience and even knowledge of Japan was closely managed by this group even when in Japan: Hwang and Pak depended entirely on Shigenobu and their other guides relaying the latest news to them. For this reason, their account of these critical few days in Osaka must be considered alongside the other sources available. Recent Japanese scholarship on Hideyoshi‚Äôs foreign policy, and the breakdown of negotiations in particular, suggest the outline sequence of events and critically, Hideyoshi‚Äôs main motivation for ordering another invasion, were indeed most probably as represented in the ambassadors‚Äô diaries ‚Äď which become important corroborating evidence.

73 This is quite a different version of events traditionally reproduced in English-language scholarship on the war, in which Hideyoshi instead became enraged when he discovered he was to be subordinate to China (which he had earlier planned to conquer).

74

The excerpts cited here demonstrate that the two diaries are not only an important source for studying the breakdown of negotiations, but also for considering how the authors and their contemporaries thought about Korean and Japanese identities. The anecdotes about people born in ChosŇŹn but taken to Japan are particularly revealing about their ideas of belonging. When Hwang was speaking with the king, belonging of course meant subjecthood, but regardless of context it seems language was an important marker of identity. Language‚Äôs importance is not something that we could have taken as given. ChosŇŹn scholars prided themselves on their knowledge of Chinese language and literature, and espoused universalising Neo-Confucian norms that linking them more to Chinese scholars than to the Koreans of lower classes. As regards the Japanese, the diarists‚Äô depictions of humane acts by their Japanese hosts point to how the embassy‚Äôs working with Japanese people in a close, co-operative context would have encouraged a weakening of caricatures and a fuller understanding of the Japanese as human beings. The transmission of such a story to a wider ChosŇŹn audience via Hwang‚Äôs diary may have also added a depth and complexity to people‚Äôs imaginings of Japan and the Japanese ‚Äď if they were open to such ideas.

Notes

Reference List

- Atobe Makoto Ť∑°ťÉ®šŅ°. ‚ÄúToyotomi seiken ki no taigai kankei to chitsujokan‚ÄĚ ŤĪäŤá£śĒŅś®©śúü„ĀģŚĮ匧ĖťĖĘšŅā„Ā®Áß©ŚļŹŤ¶≥ [Foreign Relations and View of the World Order during the Toyotomi Government Period]. Nihon-shi kenkyŇę śó•śú¨ŚŹ≤Á†ĒÁ©∂ 585 (2011): 56‚ąí82.

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1982.

- Cho WŇŹllae. ‚ÄúPak Hongjang‚ÄĚ śúīŚľėťē∑. Hanguk Minjok Munhwa DaebaekkwasajŇŹn. The Academy of Korean Studies. 1997. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr.

- Han MyŇŹnggi ťüďśėéŚüļ. ‚ÄúImjin waeran chikjŇŹn Dong-Asia chŇŹngsae‚ÄĚ žěĄžßĄžôúŽěÄ žßĀž†Ą ŽŹôžēĄžčúžēĄ ž†ēžĄł [East Asia Immediately before the Imjin War]. Han-Il gwan‚Äôgae-sa yŇŹngu ŪēúžĚľÍīÄÍ≥Ąžā¨žóįÍĶ¨ 43 (2012): 175-214.

- Hawley, Samuel Jay. The Imjin War: Japan’s Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China. Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch; Berkeley: Royal Asiatic Society, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 2008.

- Hou Jigao šĺĮÁĻľťęė. ‚ÄúQuan zhe bing zhi kao‚ÄĚ ŚÖ®śĶôŚÖĶŚą∂ŤÄÉ [Military System of the Entire Zhe Region]. In Siku quan shu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui, ed. Siku quan shu cunmu congshu ŚõõŚļęŚÖ®śõłŚ≠ėÁõģŚŹĘśõł vol. zi 31, Jinan: Qi lu shu she, 1995.

- Hwang Shin ťĽÉśĄľ. ‚ÄúIlbon wanghwan ilgi‚ÄĚ śó•śú¨ŚĺÄťāĄśó•Ť®ė. In Minjok munhwa ch‚Äôuch‚ÄôŇŹnhoe, ed. (KugyŇŹk) Haehaeng ch‚Äôongjae (ŚúčŤ≠Į) śĶ∑Ť°ĆÁłĹŤľČ, Seoul: Minjok munhwa ch‚Äôuch‚ÄôŇŹnhoe, 1974.

- ‚ÄĒ‚ÄĒ‚ÄĒ. Ilbon wanghwan ilgi, n.d. Kyoto University Kawai Archive šļ¨ťÉĹŚ§ßŚ≠¶ś≤≥ŚźąśĖáŚļę.

- Kang Hang Śßúś≤Ü. ‚ÄúKanyang nok‚ÄĚ ÁúčÁĺäťĆĄ. In Minjok munhwa ch‚Äôuch‚ÄôŇŹnhoe, ed. (KugyŇŹk) Haehaeng ch‚Äôongjae (ŚúčŤ≠Į) śĶ∑Ť°ĆÁłĹŤľČ. Seoul: Minjok munhwa ch‚Äôuch‚ÄôŇŹnhoe, śįĎśóŹśĖáŚĆĖśé®ŤĖ¶śúÉ. 1974.

- Kang Hongjung ŚßúŚľėťáć. Tong sa rok śĚĪśßéťĆĄ (Record of an Eastern Voyage), n.d. In Kwan‚Äôgam nok ŤßÄśĄüťĆĄ (Record of That Seen and Sensed). Nagoya Castle Museum Library, Saga.

- Ledyard, Gari. ‚ÄúConfucianism and War: The Korean Security Crisis of 1598.‚ÄĚ Journal of Korean Studies 6 (1989): 81-119.

- Matsuda Tokihiko śĚĺÁĒįśôāŚĹ¶. ‚Äú‚ÄôYŇćchŇęi dansŇć‚Äô no saikentŇć‚ÄĚ „ÄĆŤ¶Āś≥®śĄŹśĖ≠ŚĪ§„Äć„ĀģŚÜ朧úŤ®é [A Re-Evaluation of Precaution Fault Zones]. KatsudansŇć kenkyŇę śīĽśĖ≠ŚĪ§Á†ĒÁ©∂ (1996): 1-8.

- Oh HŇ≠imun Śź≥ŚłĆśĖá. Swaemi rok ťéĽŚįĺťĆĄ (Record of a Refugee), n.d. Jangseogak Royal Archives. http://yoksa.aks.ac.kr.

- Sajima Akiko šĹźŚ≥∂ť°ēŚ≠ź. ‚ÄúHideyoshi‚Äôs View of ChosŇŹn Korea and Japan-Ming Negotiations.‚ÄĚ In James Bryant Lewis ed., The East Asian War: International Relations, Violence, and Memory. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2015.

- SŇŹnjo sillok Śģ£Á•ĖŚĮ¶ťĆĄ (Annals of the SŇŹnjo Reign), n.d. National Institute of Korean History. http://sillok.history.go.kr.

- Swope, Kenneth. A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

- Takeda Mariko ś≠¶ÁĒįšłáťáĆŚ≠ź. ‚ÄúToyotomi Hideyoshi no Ajia chiri ninshiki‚ÄĚ ŤĪäŤá£ÁßÄŚźČ„Āģ„āĘ„āł„āĘŚúįÁźÜŤ™ćŤ≠ė [Toyotomi Hideyoshi‚Äôs Geographical Conception of Asia]. Kaiji-shi kenkyŇę śĶ∑šļ茏≤Á†ĒÁ©∂ 67 (2010): 56-73.

- Tansil kŇŹsa šłĻŚģ§ŚĪÖŚ£ę. Imjin nok Ś£¨ŤĺįťĆĄ (Record of the Imjin Year), n.d. Jangseogak Royal Archives. http://yoksa.aks.ac.kr.

- Yi Taejin. ‚ÄúHwang Shin‚ÄĚ ťĽÉśĄľ. Hanguk Minjok Munhwa DaebaekkwasajŇŹn. The Academy of Korean Studies, 1998. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr.