Abstract

-

Chinsan Sego жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ is a collection of literary works compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng е§ңеёҢеӯҹ, containing the poems and writings of his grandfather, father, and elder brother. The collection includes the works of TongjЕҸng йҖҡдәӯ Kang Hoebaek е§ңж·®дјҜ, WanyЕҸkchae зҺ©жҳ“йҪҠ Kang SЕҸktЕҸk е§ңзў©еҫ·, and Injae д»ҒйҪӢ Kang HЕӯianе§ңеёҢйЎ”.

Chinsan sego is particularly significant as it is one of the earliest sego (a type of family literary collection) publications from the ChosЕҸn Dynasty. It served as a model for later sego compilations, profoundly influencing the genre. Its importance was officially recognized on December 18, 1998, when it was designated as Treasure No. 1290 (privately owned) by the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea.

The collection, which Kang HЕӯimaeng first began compiling, continued to be supplemented with the literary works of other key figures from the Chinju Kang clan throughout the ChosЕҸn Dynasty, adding to its historical value and legacy. A thorough examination of Chinsan sego is necessary, as numerous copies (including incomplete ones) have been identified in institutions both in Korea and abroad.

Accordingly, this study aims to organize and systematize the lineage of Chinsan sego editions to identify their publication characteristics and examine the editorial intent involved. Consequently, the research ultimately classifies the collection into five distinct editionsвҖ”the First Edition (1474), the 1491 Edition, the 1658 Edition, the 1845 Edition, and the 1959 EditionвҖ”and summarizes the unique characteristics of each.

In addition, this study observed that while the early Chinsan sego compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng was primarily based on the consciousness of вҖңthe succession of a clanвҖҷs moral works and literary legacy,вҖқ the versions published after the 1658 edition under the title Chinsan sego sokjip жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝзәҢйӣҶreflected a shift in consciousness toward вҖңthe commemoration of a neglected talent жҮ·жүҚдёҚйҒҮ and the succession of the will of forebears йҒәж—Ё.вҖқ

In particular, a distinction from the earlier compilation was found in the fact that most figures added to the Chinsan segosokchip, including Kang KЕӯksЕҸng е§ңе…ӢиӘ , were those who possessed great literary talent but passed away early without reaching high government positions.

-

Keywords: Chinsan sego жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ, sego дё–зЁҝ, Kang HЕӯimaeng е§ңеёҢеӯҹ, Chinsan segosokchip жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝзәҢйӣҶ, Sasukjaejip з§Ғж·‘йҪӢйӣҶ, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng е§ңе…ӢиӘ

Introduction

This study aims to organize and classify the editions of Chinsan sego жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ [Collected Works of Three Generations of the Chinsan Clan], identify the characteristics related to each edition and its publication, and thereby examine its editorial intent.

Chinsan sego is a collected works compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng е§ңеёҢеӯҹ (1424-1483), which brings together the writings of his grandfather, father, and elder brother. It contains the poetry and prose of TongjЕҸng йҖҡдәӯ Kang Hoebaek е§ңж·®дјҜ (1357-1402), WanyЕҸkchae зҺ©жҳ“йҪҠ Kang SЕҸktЕҸk е§ңзў©еҫ· (1395-1459), and Injae д»ҒйҪӢ Kang HЕӯian е§ңеёҢйЎ” (1418-1465). Notably, Chinsan sego was compiled earlier than any other sego дё–зЁҝ вҖңfamily anthologiesвҖқ published during the ChosЕҸn dynasty. It served as a model for subsequent compilations of this genre and exerted a significant influence, thereby holding considerable scholarly importance.

Meanwhile,

IshЕҚ Nihon-den з•°з§°ж—Ҙжң¬дјқ, the work of Matsushita Kenrin жқҫдёӢиҰӢжһ— (1637-1704), who was active during the Edo period in Japan, included two poems by Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, вҖңSong KochвҖҷЕҸmchu pongsa IlbonвҖқ йҖҒй«ҳеғүжЁһеҘүдҪҝж—Ҙжң¬ and вҖңSong Sin pЕҸmong kwi IlbonвҖқ йҖҒз”іжіӣзҝҒжӯёж—Ҙжң¬, as well as the entry вҖңIlbon chвҖҷЕҸkchвҖҷokhwaвҖқ ж—Ҙжң¬иә‘иә…иҠұ from Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs

Yanghwa sorok йӨҠиҠұе°ҸйҢ„ [The Little Book for Growing Flowers]. All of these pieces are also found in

Chinsan sego. This indicates that

Chinsan sego was circulated in Japan at that time.

1 Furthermore, the fact that

Chinsan sego was among the books brought to Japan by the

tвҖҷongsinsa йҖҡдҝЎдҪҝ вҖңKorean envoyвҖқ in 1748 further underscores the recognition of its importance.

2 The designation of this work as National Treasure No. 1290 (privately held) by the Cultural Heritage Administration of South Korea on December 18, 1998, can be understood as recognition of its significance.

After its initial publication, Chinsan sego underwent a second printing in which the literary works of additional authors were incorporated. Besides Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian, works by ChвҖҷwijuk йҶүз«№ Kang KЕӯksЕҸng е§ңе…ӢиӘ (1526-1576), MaesЕҸ жў…еў… Kang ChonggyЕҸng е§ңе®—ж…¶ (1543-1580), and Hogye еЈәжәӘ Kang Chinhwi е§ңжҷӢжҡү (1567-1596) were added. Subsequently, additional pieces by Yongjae ж…өйҪӢ Kang TЕҸkpu е§ңеҫ·жәҘ (1668-1749), SamhЕӯidang дёүзЁҖе Ӯ Kang Chuje е§ңжҹұйҪҠ (1701-1778), Kakpijae иҰәйқһйҪӢ Kang Chunam е§ңжҹұеҚ— (1716-1784), and ChЕҸnam е…ёеәө Kang ChЕҸnghwan е§ңйјҺз…Ҙ (1741-1816) were incorporated in a later reprint. In this way, Chinsan sego, which was initially published under the initiative of Kang HЕӯimaeng, continued to be revised throughout the ChosЕҸn period, with the poetry and prose of key members of the Chinju Kang lineage added over time. This makes its ongoing transmission and accumulation of literary works historically significant. In this context, scholarly efforts have been made to identify and organize the various editions of Chinsan sego.

Pak YЕҸngdon considered that the first edition of

Chinsan sego, designated as National Treasure No. 1290, was published in 1476 (the 7th year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign), and he briefly noted that it was subsequently reprinted a total of six times.

3 Meanwhile, after its designation as a National Treasure, Sim Ujun raised a question regarding the 1476 edition, arguing that certain passages, вҖңд»ҒйҪҠд№ӢйӨҠиҠұйҢ„зҲІз¬¬еӣӣвҖқ in the postface by Kim Chongjik йҮ‘е®—зӣҙ (1431-1492) were later added, and therefore it cannot be regarded as the true first edition.

4

Yu PвҖҷungyЕҸn regarded the first edition of

Chinsan sego as having been published in 1474 (the 5th year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign). He viewed a subsequent edition, which includes SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸngвҖҷsеҫҗеұ…жӯЈ (1450-1504) вҖң

Chinsan sego palвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝи·Ӣ and Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs вҖң

Chinsan sego i Chinmok palвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ移жҷүзү§и·Ӣ designated as National Treasure No. 1290, as an intermediate edition, thus differing from Pak YЕҸngdonвҖҷs interpretation.

5

An IksЕҸng conducted a comprehensive study of family anthologies published during the ChosЕҸn dynasty, in which he also addressed

Chinsan sego.

6 He shared Yu PвҖҷungyЕҸnвҖҷs view that the first edition was published in 1474 (the 5th year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign). In addition, he noted that a total of five editions were published around the same period following the initial printing, and he examined the subsequent publications in the form of

sokchip зәҢйӣҶ вҖңsupplemental collections.вҖқ

Recently, ChвҖҷoe KyЕҸnghun analyzed

Chinsan sego by focusing on extant family anthologies published in the early ChosЕҸn period and tracing the circumstances of later editions. This study clarified that, following the first edition of

Chinsan sego in 1474 (the 5th year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign), a reprint was issued in 1491, which involved a woodblock reproduction of Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs collected works,

Sasukjaejip з§Ғж·‘йҪӢйӣҶ [The Collection of Kang HЕӯimangвҖҷs Works]. Additionally, ChвҖҷoe introduced to scholarship the KyemyЕҸng University edition of

Chinsan sego, which was published in 1805.

7

Previous studies have primarily focused on issues related to the first edition of Chinsan sego, and in particular, the research of An IksЕҸng and ChвҖҷoe KyЕҸnghun has made it possible to ascertain much of the overall context of its publication, which represents a significant achievement. However, since more than 60 copies of Chinsan sego (including incomplete editions) are currently held in domestic institutions, a comprehensive review is necessary to determine whether they represent the same edition, to classify them according to textual lineage, and thereby to clarify the overall publication history of Chinsan sego. In addition, it is essential to correct inaccuracies found in previous studies or by the institutions holding the copies, and to revise the publication dates and related details accordingly.

Building on the achievements of previous studies, this research aims to review the overall status of Chinsan sego editions, classify them according to textual lineage, and correct elements deemed erroneous, while examining the characteristics and significance of Chinsan segoвҖҷs publication throughout the ChosЕҸn period.

A Review of Previous Research on the Editions and Publication of Chinsan sego

The textual lineages of

Chinsan sego proposed in previous studies are first examined. Pak YЕҸngdon identified a total of six lineages of

Chinsan sego, An IksЕҸng recognized ten, and ChвҖҷoe KyЕҸnghun identified five. Based on this information, I will conduct a comparative analysis to clarify any errors or unknowns regarding the publication years, with the aim of establishing accurate dates and presenting a finalized classification of the textual lineages. First, the textual lineages proposed in previous studies can be summarized as follows

.

в‘ As mentioned above, Pak YЕҸngdon judged that the year of publication of

Chinsan sego was 1476, based on the postfaces written by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng and Kang HЕӯimaeng. However, subsequent researchers have regarded 1474 as the year of the first edition, earlier than the date of the postfaces. This view is based on the

huji еҫҢиӯҳ вҖңpostscriptвҖқ recording the process by which Kim ChЕҸngjik, while serving as the magistrate of Hamyang е’ёйҷҪ, supervised the carving of the woodblocks for

Chinsan sego, and on the postface in which Kang HЕӯimaeng recorded the transfer of these woodblocks from Hamyang to Chinju жҷӢе·һ.

8 According to this evidence, the woodblocks for

Chinsan sego were completed in 1473, and in the following spring Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs

Yanghwa sorok was additionally imprinted and published.

9 In this context, it appears that the postfaces by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng were received in 1476, and a postface recording the transfer of the woodblocks was added to the already published edition.

в‘Ў The Kyujanggak edition (еҘҺ6691), believed to be a reprint of the revised content of the first edition in 1478, contains some structural inconsistencies: following volume 1 is вҖңInjae haengjangвҖқ д»ҒйҪӢиЎҢп§ә, after volume 2 is вҖңTвҖҷongjЕҸng haengjangвҖқ йҖҡдәӯиЎҢп§ә, after volume 4 is вҖңWanyЕҸkchae haengjangвҖқ зҺ©жҳ“йҪӢиЎҢп§ә, and at the end of the volume is Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs вҖңYanghwa sorok sЕҸвҖқ йӨҠиҠұе°ҸйҢ„еәҸ. Although these arrangements show editorial errors, the script style and physical features of the publication (11 lines with 19 characters per line, sohЕӯkku е°Ҹй»‘еҸЈ вҖңsmall black punctuation marks,вҖқ sangha naehyang hЕӯgЕҸmi дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ вҖңinward-facing black fishtail marks at top and bottomвҖқ) are similar to those of the first-edition lineage. Moreover, considering the poor condition of the printed surface, it may be regarded as a later impression. However, since there is no clear evidence to specify 1478 as the exact year of publication, further detailed verification is required.

в‘ў The National Library of Korea edition (еҸӨ3648-00-104) has been dated differently in the literature, with some sources citing 1483 and others 1491. The view that it was published in 1484 is based on the fact that this edition contains the

Sasukchaejip, which was commissioned by King SЕҸngjong, and draws on related entries in

ChosЕҸn wangjo sillok жңқй®®зҺӢжңқеҜҰйҢ„.

10 Because the

Sasukchaejip was printed using the

kapchinja з”Іиҫ°еӯ— вҖңKapchin type,вҖқ it is also referred to as the вҖңKapchinja edition.вҖқ

11 However, the large-capacity types of the Kapchin type were completed in December 1484,

12 and

WanghyЕҸnggong sijip зҺӢиҚҠе…¬и©©йӣҶ, believed to be the first work printed using the Kapchin type, was distributed in March 1485.

13 These records indicate that the actual publication likely occurred after 1485. Consequently, the publication of the

Chinsan sego including

Sasukchaejip can only be considered possible after 1485. The 1491 publication will be discussed in detail in the following chapter.

в‘Ј The view that it was published as an 8-volume, 2-fascicle edition in 1653 is also based on unclear evidence and may, in fact, result from a misdating that should be attributed to 1658. в‘Ө It also seems reasonable to consider that the woodblock movable type edition printed during King YЕҸngjoвҖҷs reign was actually published in 1805 or 1845.

The 1845 edition (woodblock movable type print) of

Chinsan sego includes a preface by Kim Sangjik йҮ‘зӣёзЁ· (1779-1851), a descendant of Kim Chongjik (the 11th year, 5th month of King HЕҸnjongвҖҷs reign). In some cases, this preface was mistakenly attributed to a different individual with the same name, Kim Sangjik йҮ‘зӣёзЁ· (1661-1721), and based on his lifespan, the preface was dated to 1685 (the 11th year of King SukchongвҖҷs reign). On the basis of this misattribution, the publication date of

Chinsan sego was sometimes also assumed to coincide with the preface. However, Kim Sangjik, who had been born in 1661, passed the special civil service examination in 1695 (the 21st year of King SukchongвҖҷs reign), making it unlikely that he would have written a preface for another personвҖҷs work at that time. Furthermore, this individual belonged to the YЕҸnan 延е®ү lineage, whereas the preface identifies the author as a descendant of Kim Chongjik of the SЕҸnsan Kim clan. Therefore, it is more reasonable to attribute the preface to the Kim Sangjik born in 1779.

14 Accordingly, the woodblock movable type print edition compiled by Kang Kyuhoe е§ңеҘҺжңғ that includes Kim SangjikвҖҷs preface corresponds to the 1845 edition.

Synthesizing the above, the editions can be classified into the following five lineages

.15

Examination of Chinsan sego Editions and the Establishment of their Lineages

First edition (woodblock print) 4 volumes in 1 fascicle: single-border frame on all four sides, 11 lines with 19 characters per line, small black punctuation marks е°Ҹй»‘еҸЈ, inward-facing black fish-tail marks at top and bottom дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ.

To begin, the contents of Chinsan sego are as follows:

- Prefaces by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng, ChвҖҷoe Hang, and ChЕҸng ChвҖҷangson

- Volume 1: Eulogy of Kang Hoebaek, TвҖҷongjЕҸngjip йҖҡдәӯйӣҶ (including 94 poems)

- Volume 2: Eulogy of Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, WanyЕҸkchaejip зҺ©жҳ“йҪӢйӣҶ (including 37 poems and 6 prose pieces)

- Volume 3: Eulogy of Kang HЕӯian, Injaejip д»ҒйҪӢйӣҶ (including 66 poems)

- Volume 4: Preface to Yanghwa sorok (by Kang HЕӯimaeng), autobiographical preface to Yanghwa sorok (by Kang HЕӯian), Yanghwa sorok, postscript to Injaesigo д»ҒйҪӢи©©зЁҝ (by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng and ChвҖҷoe Ho)

- вҖңChinsan sego hujiвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝеҫҢиӯҳ (by Kim Chongjik), вҖңChinsan sego palmunвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝи·Ӣж–Ү (by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng), вҖңChinsan sego i Chinmok palвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ移жҷүзү§и·Ӣ (by Kang HЕӯimaeng)

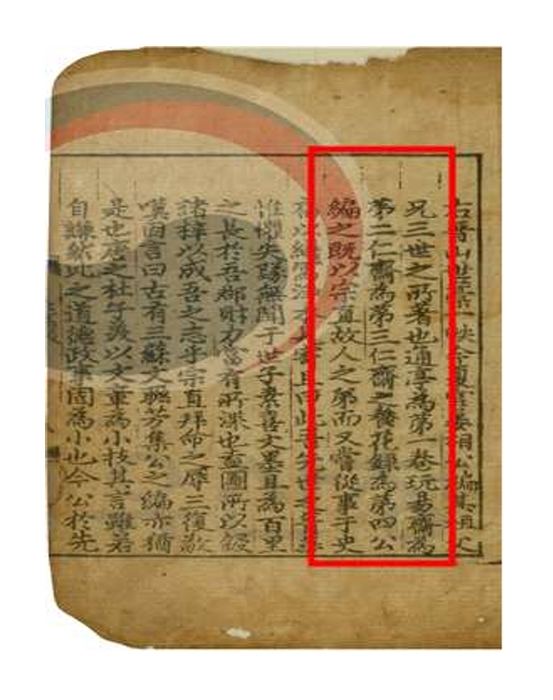

The first edition most widely known is the Pak YЕҸngdon edition, designated as National Treasure No. 1290 (privately held) by the Cultural Heritage Administration on December 18, 1998. The most notable feature of the Pak YЕҸngdon edition is that it contains Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs вҖңChinsan sego i Chinmok palвҖқ and SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸngвҖҷs вҖңChinsan sego pal,вҖқ which do not appear in other copies, making it unique even among the first-edition lineages.

Among the first-edition lineages, the ChonвҖҷgyЕҸnggak edition at SЕҸnggyunвҖҷgwan University (зЁҖ D02B-0339 v.1) differs in Kim ChongjikвҖҷs postscript from other editions. In this copy, the characters вҖңChongjikвҖқ е®—зӣҙ in the postscript are obscured by an additional sheet of paper attached only to this edition. Furthermore, at the end of the postscript, the phrase вҖңHamyang gunsu chongsЕҸn Kim Chongjik kЕӯnjiвҖқ е’ёйҷҪйғЎе®ҲеҙҮе–„йҮ‘е®—зӣҙ謹иӯҳ is similarly covered by an attached sheet. This is also presumed to be related to the literati purges related to Kim Chongjik during King YЕҸnsanвҖҷs reign, but a more detailed investigation is needed.

Meanwhile, some editions within the first-edition lineage show slight variations, such as the use of variant characters in the printed text, which can be particularly observed in Volume 4

Yanghwa sorok.

Among the first-edition lineages examined so far, the copies in which the final phrase of Yanghwa sorok reads ojongjagwi еҗҫеҫһеӯҗжӯё are the Pak YЕҸngdon edition, the ChonвҖҷgyЕҸnggak edition (зЁҖ D02B-0339 v.1), the National Library of Korea edition A (еҸӨиІҙ3648-00-103), and the National Library of Korea edition B (13-061-04060 [LKH 10512]). The copies in which it reads ojongjagwi еҗҫеҫһеӯҗж•Җ are the KoryЕҸ University edition (л§ҢмҶЎ иІҙ 408) and the National Museum edition.

1491 edition (woodblock print)16

The 1491 edition is notable for being organized under the title

Chinsan sego, following the first edition, and for comprising Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs collected works,

Sasukchaejip. This edition was republished with a preface by SЕҸng HyЕҸn жҲҗдҝ” at the request of Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs eldest son, Kang Kwisonе§ңпӨҮеӯ«, who was concerned that the limited number of copies of the first edition of

Sasukchaejip would prevent many people from accessing it.

17 A particularly noteworthy point is that it is mentioned in Yi InyЕҸngвҖҷs жқҺд»ҒжҰ®

ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmok ж·ёиҠ¬е®Өжӣёзӣ® [Bibliography of the ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil Collection]. In this record, two versions of

Chinsan sego, which compile the poetry and prose of Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs grandfather Kang Hoebaek, father Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and eldest brother Kang HЕӯian, are listed: One is

Chinsan sego (partial copy, 1 volume, 1 fascicle) containing only Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs

Yanghwa sorok, and the other is

Chinsan sego (partial copy, 1 fascicle) containing portions of Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs collected works,

Sasukchaejip. The description of the second copy,

Chinsan sego (partial copy, 1 fascicle), can be summarized as follows.

18

- Edition: Woodblock print (reprint in the Kapchin type)

- Publication Information: [Chinju] Kang Kwison, the 22nd year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign (1491)

- Physical Description: 4 volumes in 1 fascicle (partial copy): double-border frame on all four sides еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ, half-frame layout еҚҠйғӯ, 20.0Г—15.5cm, ruled жңүз•Ң, half-page layout еҚҠи‘ү with 12 lines and 19 characters per line, black punctuation marks й»‘еҸЈ

- Notes:

Order of Sections: Volume 18вҖ“ вҖңNokвҖқ йҢ„ and вҖңSЕҸlвҖқ иӘӘ; Volume 19вҖ“ вҖңChвҖҷanвҖқ и®ҡ, вҖңSЕҸвҖқ жӣё, вҖңChвҖҷaekвҖқ зӯ–; Volume 20вҖ“ вҖңSangsЕҸвҖқ дёҠжӣё and вҖңChapchвҖҷЕҸвҖқ йӣңи‘—; Volume 21вҖ“ вҖңChemunвҖқ зҘӯж–Ү, вҖңSomunвҖқ з–Ҹж–Ү, вҖңMyЕҸngвҖқ йҠҳ, вҖңMyojiвҖқ еў“иӘҢ, вҖңPimyЕҸngвҖқ зў‘йҠҳ, вҖңHaengjangвҖқ иЎҢп§ә, and вҖңChЕҸnвҖқ еӮі

At end of volume еҚ·жң«: вҖңиҫӣдәҘ(1491)жҡ®жҳҘжңүж—Ҙй–ҖдәәеӨҸеұұзЈ¬еҸ”(жҲҗдҝ”)謹и·ӢвҖқ

Manuscript notes еўЁжӣё: вҖңйҢҰе·қжңҙж°ҸвҖқ(еҚ·йҰ–) вҖңеӨҸеҜ’дәӯвҖқ(еҚ·жң«)

The manuscript notes

kЕӯmchвҖҷЕҸn pak ssi йҢҰе·қжңҙж°Ҹ вҖңthe KЕӯmchвҖҷЕҸn Pak clanвҖқ and

hahanjЕҸng еӨҸеҜ’дәӯ вҖңHahan PavilionвҖқ in the description refer to Sogo еҳҜзҡҗ Pak SЕӯngim жңҙжүҝд»» (1517-1586).

19 However, Hahan Pavilion was actually the pavilion constructed by Pak SЕӯngimвҖҷs son, Pak Rok жңҙжјү (1542-1632), and the name was given by Pak SЕӯngim. There is no evidence that Pak SЕӯngim himself used HahanjЕҸng as a sobriquet, whereas it can be confirmed that the name was used as a sobriquet for Pak Rok.

20 As Pak SЕӯngimвҖҷs book collection was passed down to his son Pak Rok and grandson Pak Hoemu жңҙжӘңиҢӮ (1575-1666), it appears that his descendants added the inscription вҖңHahanjЕҸngвҖқ as a manuscript note to the inherited books to indicate that they belonged to Pak SЕӯngimвҖҷs collection.

21

According to the cataloging notes in

ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmok, Kang Kwison appears to have incorporated

Sasukchaejip into

Chinsan sego rather than publishing it as a separate collection, thereby continuing the original intent with which Kang HЕӯimaeng compiled

Chinsan sego. This edition is particularly significant because it demonstrates that the complete text of

Sasukchaejip, of which a single complete copy now survives only at HЕҚsa Bunko 蓬е·Ұж–Үеә« in Japan, was also available in Korea. Notably, physical copies of this edition are held at the National Library of Korea, YЕҸnse University Library, and ChвҖҷungnam National University Library. The bibliographic details of the editions held by each institution are summarized as follows

.

The National Library of Korea edition (еҸӨ3648-00-104) contains Chinsan sego volumes 5-9, corresponding to Sasukchaejip volumes 1-5. Another National Library of Korea edition (еҸӨ3648-00-106) contains Chinsan sego volumes 12-13, aligned with Sasukchaejip volumes 8-9. The YЕҸnse University and ChвҖҷungnam National University copies contain Chinsan sego volumes 18-21, corresponding to Sasukchaejip volumes 14-17. From this, it can be seen that the Kapchin type reprint began numbering from volume 5, following the previously published Yanghwa sorok, Chinsan sego volume 4. The current locations of Chinsan sego volumes 10-11 and 14-17 (corresponding to Sasukchaejip volumes 6-7 and 10-13) are unknown.

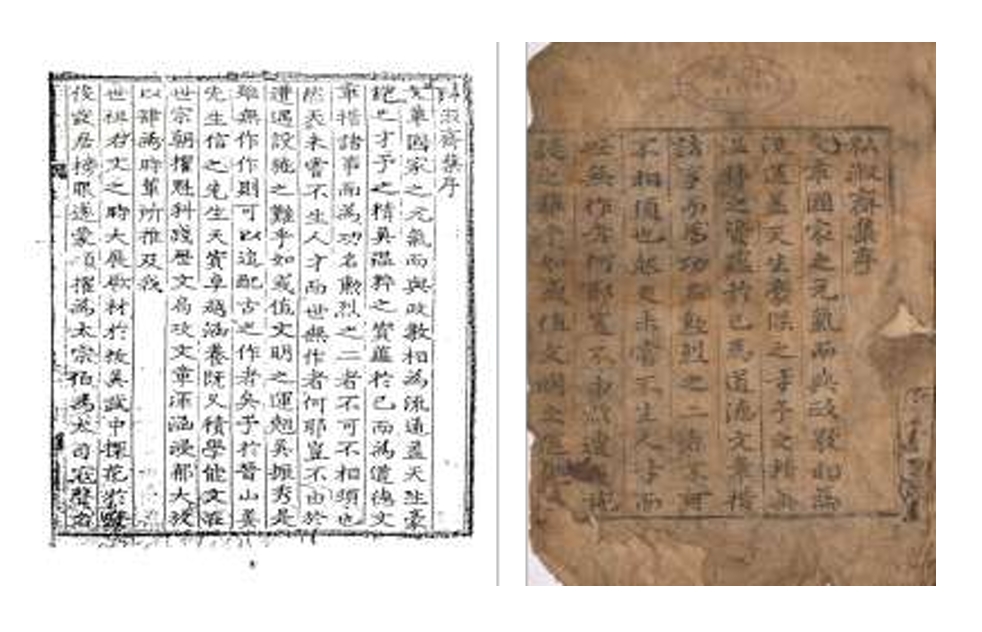

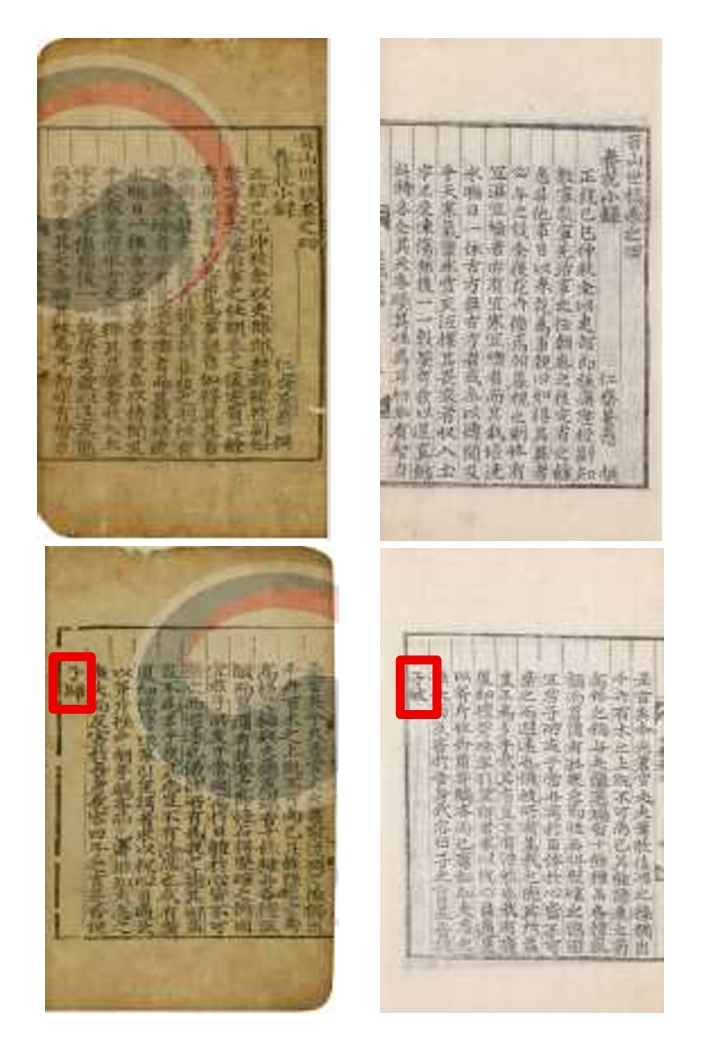

Among the Kapchin type reprints, the YЕҸnse University copy is marked with

kЕӯmchвҖҷЕҸn pakssi йҢҰе·қжңҙж°Ҹ on the first leaf (title page) of the volume еҚ·йҰ–йЎҢйқў, and bears the seals, such as

haksan jinjang еҜүеұұзҸҚи—Ҹ (title page),

chЕҸnju yissi е…Ёе·һп§Ўж°Ҹ (end page),

chвҖҷЕҸngbunsil ж·ёиҠ¬е®Ө (end page), which were Yi InyЕҸngвҖҷs ownership seal. It is therefore considered to be в‘Ў

Chinsan sego (partial, 1 fascicle) mentioned in the

ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmok.22

As noted earlier in connection with

ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmokвҖҷs description, the manuscript inscription

kЕӯmchвҖҷЕҸn pakssi refers to Pak SЕӯngim, and it can be understood as having been preserved in his private book repository, HahanjЕҸng, before entering Yi InyЕҸngвҖҷs collection and being recorded in the

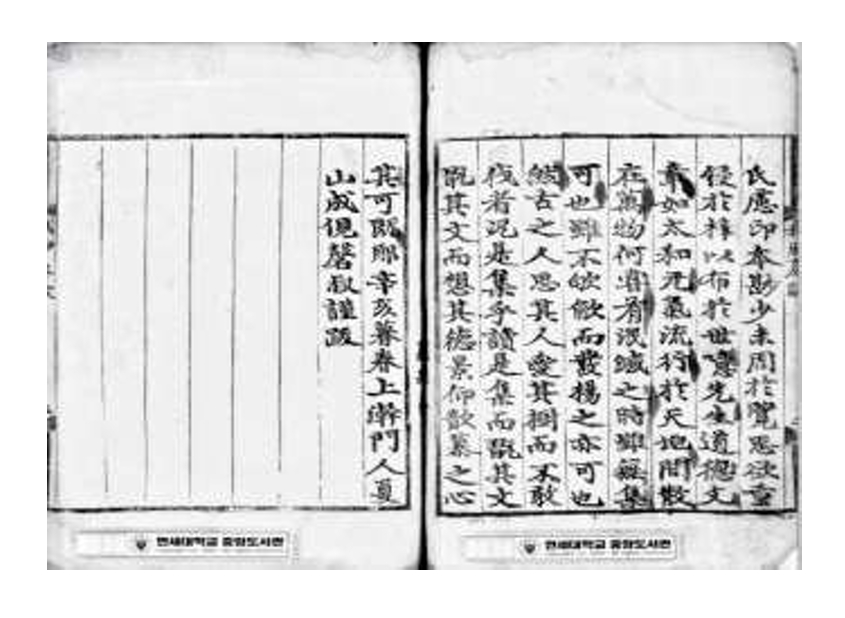

ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmok. A notable feature of this edition is that it does not reproduce the preface by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng, but was separately carved in large type along with the postface by SЕҸng HyЕҸn. Moreover, it shows corrections reflecting proofreading marks indicated in the head of the volume еӨ©й ӯ of the first edition (the HЕҚsa Library edition) as well as evidence of independent corrections. In addition, some titles of works were revised in this edition

.

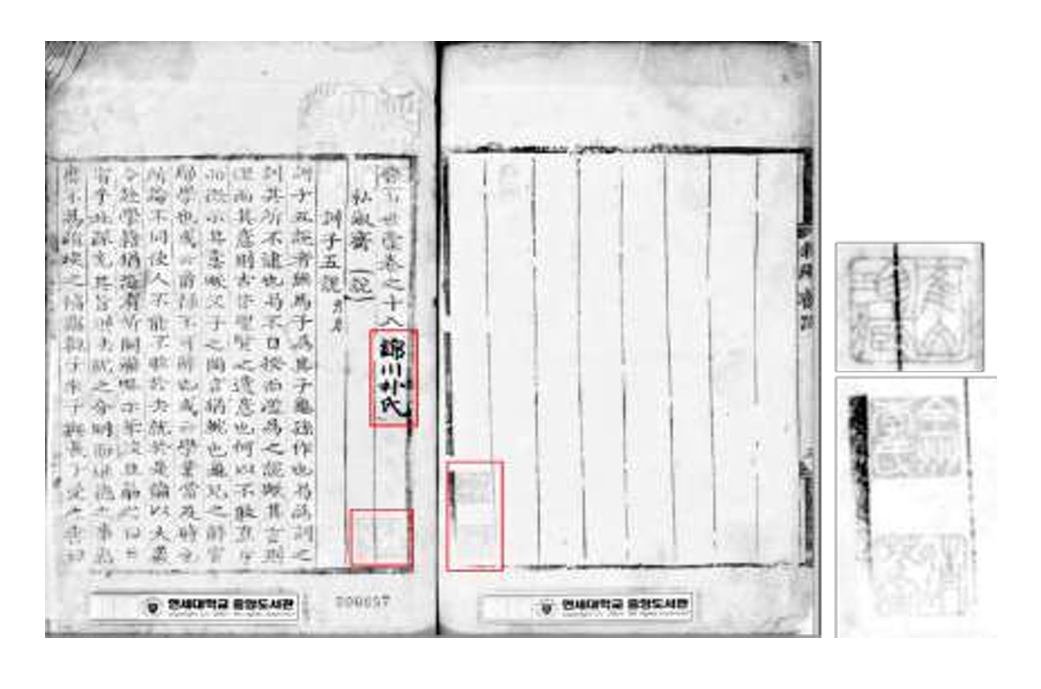

The 1658 edition was compiled into two fascicles by Kang Yuhu е§ңиЈ•еҫҢ (1606-1666), the great-grandson of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, who added the supplementary collection, and was published with prefaces by Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk жқҺжҷҜеҘӯ (1595-1671) and ChЕҸng TukyЕҸng й„ӯж–—еҚҝ (1597-1673).

Among the 1658 edition series, the Kyujanggak copy (еҘҺ6859-v.1-2) consists of two fascicles: the original collection and the supplementary collection. The original collection contains the poems and prose of Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸkdЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian as the contents of the existing Chinsan sego, while the supplementary collection includes works by Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, Kang ChonggyЕҸng and Kang Chinhwi. This indicates that Kang Kwison did not follow the precedent of incorporating Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs Sasukchaejip into Chinsan sego, but instead compiled it independently. This is likely because Sasukchaejip was also published as a standalone edition and contained a greater volume of material compared to the works of other individuals.

By contrast, the National Library of Korea edition (еҸӨ3647-562) consists solely of the supplementary collection in two fascicles. The upper collection

kЕҸnjip д№ҫйӣҶ is organized as volume 1 of

ChвҖҷwijuk yugo (by Kang KЕӯksЕҸng), while the lower collection konjip еқӨйӣҶ compiles

ChвҖҷwijuk yugo volume 2,

MaesЕҸ yugo (by Kang ChonggyЕҸng) volume 3, and

Hogye yugo (by Kang Chinhwi) volume 4. Although it is not possible to determine definitively the chronological relationship between this edition and the Kyujanggak copy, which binds

ChвҖҷwijuk yugo,

MaesЕҸ yugo, and

Hogye yugo into a single volume, the presence of the library seals sigangwЕҸn дҫҚи¬ӣйҷў вҖңCrown Prince Tutorial OfficeвҖқ and

chвҖҷunbangjang жҳҘеқҠи—Ҹ вҖңCollections of Crown Prince Tutorial OfficeвҖқ suggests that the National Library copy was printed earlier, and that the later reprint bound the original collection and the supplementary collection of

Chinsan sego together as a single set. Furthermore, if Kang Yuhu originally intended to compile only the supplementary collection, it is possible that the edition of

Chinsan sego that incorporated

Sasukchaejip may not have been part of his publication plan from the outset.

23

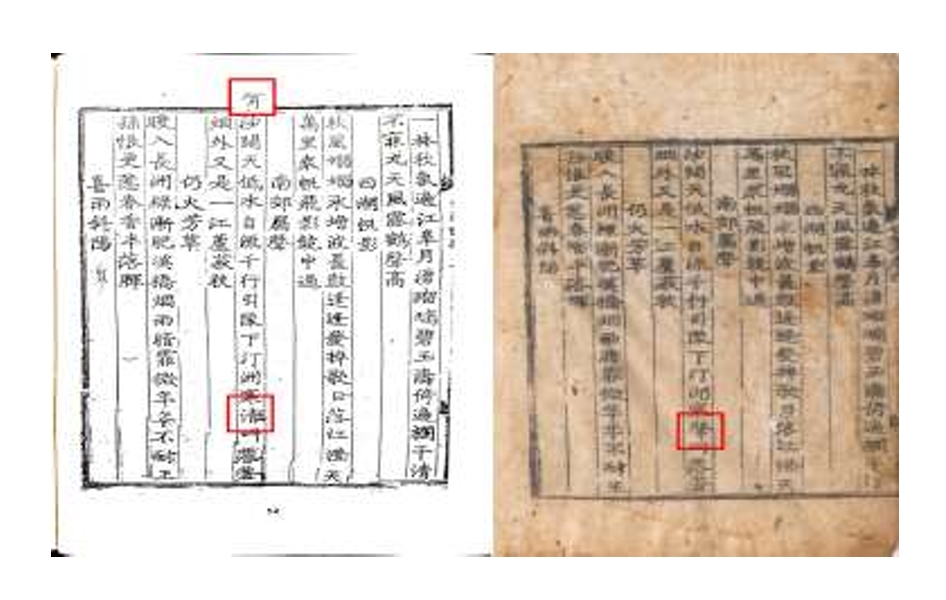

It is also noteworthy that, in publishing the original collection based on the existing Chinsan sego, a copy in which the final phrase of volume 4, Yanghwahae йӨҠиҠұи§Ј [Notes on Cultivating Flowers], is inscribed as вҖңеҗҫеҫһеӯҗж•ҖвҖқ was used as the source text. This allows us to infer certain circumstances regarding the publication of the original and supplementary collections.

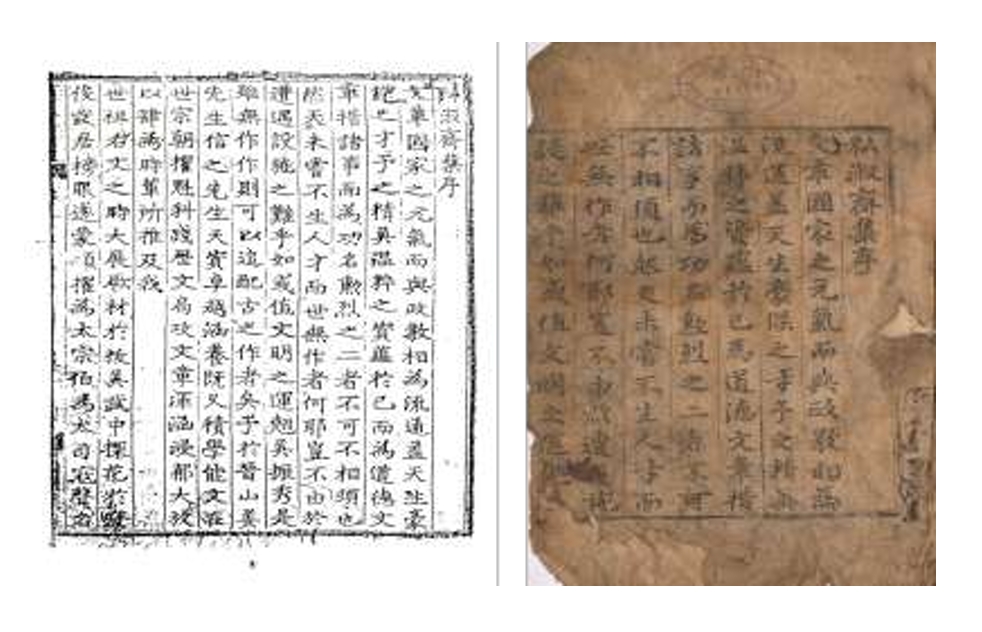

1845 edition (woodblock print)

The 1845 edition belongs to the series that includes the postface by Kim Sangjik (the 11th-generation descendant of Kim Chongjik) and is composed of three volumes in one fascicle. Notably, Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs

Yanghwa sorok is absent. In particular, with the omission of

Yanghwa sorok, the phrase вҖңд»ҒйҪҠд№ӢйӨҠиҠұйҢ„еҜ«з¬¬еӣӣвҖқ in Kim ChongjikвҖҷs postscript was also removed, which is a distinctive feature of this edition

.

As noted above, the 1845 edition is understood to include a postface by Kim Sangjik, a descendant of Kim Chongjik, written in 1845 (the 11th year of King HЕҸnjongвҖҷs reign). As also mentioned in previous studies, its most distinctive feature is that it excludes Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs Yanghwa sorok and other prose works, containing only poetry. According to Kim SangjikвҖҷs postface, Kang Kyuhoe е§ңеңӯжңғ, the thirteenth-generation descendant of Kang HЕӯimaeng, compiled a second вҖңsupplementary collectionвҖқ following the Chinsan sego sokchip жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝзәҢйӣҶ [Supplementary Collection to Chinsan sego]. Under his direction, the poetry, prose, and biographical accounts of several descendants were gathered and published: Kang TЕҸkpвҖҷu (a fifth-generation descendant of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng); Kang Chuje and Kang Chunam (sons of Kang TЕҸkpвҖҷu); and Kang ChЕҸnghwan (a son of Kang Chuje). In addition, Kang Kyuhoe appended вҖңPuyingnokвҖқ йҷ„зӣҠйҢ„, a brief record of earlier ancestors who did not appear in Chinsan sego but were nevertheless figures who deserved mention. Furthermore, Chinsan sego sokchip greatly reduced and selectively included the poetry and prose of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, and it did not include Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs Yanghwa sorok. This suggests that Kang Kyuhoe placed greater emphasis on producing the newly planned вҖңsupplementary collectionвҖқ rather than on creating additional copies of the already published and widely circulated Chinsan sego.

1959 edition (lithographic edition)

The 1959 edition was published under the leadership of Kang Taegon, a descendant of Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, together with Kang ChunghЕӯi (descendant of Kang ChongdЕҸk, the eldest son of Kang Hoebaek), Kang YЕҸwЕҸn (descendant of Kang UdЕҸk, the second son of Kang Hoebaek), and Kang Chun (descendant of Kang ChindЕҸk, the third son of Kang Hoebaek). This 1959 edition, chronologically the most recent, is currently the most widely circulated edition in Korea. In this edition as well, the phrase вҖңд»ҒйҪҠд№ӢйӨҠиҠұйҢ„еҜ«з¬¬еӣӣвҖқ from Kim ChongjikвҖҷs postface is omitted. Furthermore, the postface written by Kang Taegon, who oversaw the compilation, is titled вҖңChinsan sego chunggan palвҖқ жҷӢеұұдё–зЁҝйҮҚеҲҠи·Ӣ. The structure of this edition follows that of original Chinsan sego compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng, excluding the supplementary-collection lineage. This indicates that its editorial character differs from that of the 1658 edition and the 1845 edition.

A Study of the Editorial Intent Behind Chinsan sego

The Succession of a ClanвҖҷs Moral Works and Literary Legacy

It is difficult to determine the exact moment when Kang HЕӯimaeng first conceived the compilation of the Chinsan sego, but it appears that he began the work in earnest following two key events: the conferment of the title of a kongsin еҠҹиҮЈ вҖңmeritorious subjectвҖқ вҖ” chвҖҷuchвҖҷung chЕҸngnan iktae kongsin жҺЁеҝ е®ҡйӣЈзҝҠжҲҙеҠҹиҮЈ, in July 1469 (the 1st year of King YejongвҖҷs reign), granted for his role in addressing the treason case of Nam I еҚ—жҖЎ (1441-1468), and the third-rank designation as chwari kongsinдҪҗзҗҶеҠҹиҮЈ in March 1471 (the 3rd year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign). He personally composed the haengjang иЎҢп§ә вҖңfunerary eulogyвҖқ of his grandfather Kang Hoebaek and father Kang SЕҸktЕҸk in October 1471, and in January 1472 he asked his maternal nephew Kim SunyЕҸng йҮ‘еЈҪеҜ§ (1436-1473) to write the funerary eulogy of his eldest brother Kang HЕӯian. He also collected Kang HЕӯianвҖҷs poetry and prose and received postfaces to Injae sigo д»ҒйҪӢи©©зЁҝ [Poetry Drafts by Kang HЕӯian] from SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng and his friend ChвҖҷoe Ho еҙ”зҒқ. In 1473, he obtained prefaces to Chinsan sego from Chief State Councillor Sin Sukchu з”іеҸ”иҲҹ (1417-1475), Left State Councillor ChвҖҷoe Hang еҙ”жҒ’ (1409-1474) and pongwЕҸn puwЕҸnвҖҷgun 蓬еҺҹеәңйҷўеҗӣ ChЕҸng ChвҖҷangson й„ӯжҳҢеӯ« (1402-1487) and commissioned Kim Chongjik to produce the printing blocks.

Kang HЕӯimaeng compiled

Chinsan sego with the purpose of preserving the poetry and prose of his ancestors, works that could not be issued as separate collected writings, and of transmitting them permanently to later generations.

24 Through this effort, he established the prototype of

sego genre: when the volume of a forebearвҖҷs writings was too small to merit an independent collected work, the materials could be gathered into a single book and published under the title вҖң

sego.вҖқ

25

The method of compilation that brings together the posthumous writings of multiple members of the same family can also be seen in the case of the Three Members of the samso дёүиҳҮ вҖңSo FamilyвҖқ вҖ” So Sun иҳҮжҙө (C. Su Xun), So Sik иҳҮи»ҫ (C. Su Shi), and So ChвҖҷЕҸl иҳҮиҪҚ (C. Su Zhe) as mentioned consistently in the prefaces by Sin Sukchu, ChвҖҷoe Hang, ChЕҸng ChвҖҷangson, and SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng.

26 вҖңYemunjiвҖқ и—қж–Үеҝ—in the

Songsa е®ӢеҸІ (Song History) records such works as

Samso munjip дёүиҳҮж–ҮйӣҶ [the Collected Works of the Three So] in 100 fascicles and

Samso munryu дёүиҳҮж–ҮйЎһ [the Classified Writings of the Three So] in 68 fascicles,

27 indicating that compilations combining the writings of the Three So were produced at the time. SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸngвҖҷs postface likewise notes, вҖңOnly after reading the poetry of Tu SorЕӯng жқңе°‘йҷө (C. Du Shaoling) and

SamsojipдёүиҳҮйӣҶ, did I come to understand that authors of past and present each possess their own standards of composition, while also following a family method.вҖқ

28 This reference to

Samsojip may point to the individual collected works of So Sun, So Sik, and So ChвҖҷЕҸl, but if it refers instead to a compilation that combined their writings, one may cautiously consider the possibility of some influence on the compilation of

Chinsan sego. However, works like

Samso munjip were selective anthologies that excerpted primarily prose from an extensive corpus, and thus differ in character from the

sego format, which aims to gather as comprehensively as possible the relatively small body of writings left by members of a lineage. In this sense, it is appropriate to understand that Kang HЕӯimaeng just drew upon the method of unifying the writings of several family members into a single compilation. Based on this compilation principle,

Chinsan sego secured its significance, as affirmed in the prefaces by Sin Sukchu, ChвҖҷoe Hang, and ChЕҸng ChвҖҷangson.

In his preface, Sin Sukchu noted that cases in which literary reputation is transmitted across generations are rare, citing as examples the father and sons of So Sun, who were called

sam so, or the brothers Yuk Ki йҷёж©ҹ (C. Lu Ji) and Yuk Un йҷёйҒӢ (C. Lu Yun) of the Western Jin иҘҝжҷү period. He remarked that the lineage of Kang Hoebaek and his two descendants is an uncommon instance of this phenomenon, displaying a level of refinement comparable to that of kongin е·Ҙдәә вҖңcraftsmenвҖқ or physicians who transmitted their family business and skills over several generations. In particular, he mentioned that, although Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian each possessed their own distinct literary qualities,

Chinsan sego revealed a unified family learning and family style, so cohesive that their writings appeared to originate from a single hand. In this way, he underscored the importance of the literary inheritance sustained over three generations.

29

ChвҖҷoe Hang remarked in his preface that places imbued with pure and vital energy often produced individuals distinguished either by virtuous accomplishments or by literary excellence. He suggested that the mountains and streams of Chinsan in KyЕҸngsang Province, endowed with extraordinary spiritual force, could have generated a rare case in which a single lineage produced persons who embodied both qualities across multiple generations. Through this line of reasoning, he emphasized that Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian each combined moral virtue with literary achievement, carrying this legacy forward in successive generations.

They were descendants of a household that had held high office over several generations as well as heirs who wore silk garments, dined on refined delicacies, possessed an innately elevated disposition, and remained unbound by worldly constraints. It was, in itself, an exceptional achievement that they naturally upheld an integrity as pure as ice, took poetry and writings as their family vocation, savored their blossoms and leaves, and, with sounds like gold and resonance like jade, transmitted a distinctive familial artistry that far surpassed the common crowd. Moreover, what should be said of a lineage that continued to inherit this beauty across generations, so that father and son alike maintained a lofty and elegant spirit, receiving admiration from generation to generation and rising to such heights that they seemed to rival the very mountains of Chinsan within the universe? How fitting it was, then, that this work should be titled вҖңChinsan sego.вҖқ

еӨ«д»Ҙе–¬жңЁиҹ¬иҒҜд№ӢиғӨ, зҙҲз¶әиҶҸжўҒд№ӢиЈ”, иҖҢеӨ©еҲҶиҮӘй«ҳ, дё–зҙҜдёҚе¬°, ж°·иҳ–зҲІзҙ е°ҷ, и©©жӣёзҲІйқ‘ж°Ҳ, еҗ«иӢұе’ҖиҸҜ, иҒІйҮ‘жҢҜзҺү, иҮӘеӮідёҖ家ж©ҹжқј, ж•»и¶…жөҒиј©, еӣәе·ІиҮізҹЈ. жіҒеҸҲдё–жҝҹе…¶зҫҺ, е–¬жў“зҙҜи‘ү, йӣ…иҮҙеҙўе¶ё, дё–дё–жӯҶд»°, зӣҙиҲҮжҷүе¶ҪзҲӯй«ҳ, е®Үе®ҷй–“д№Һ? еҗҚд№Ӣжӣ°жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ, дёҚдәҰе®ңд№Һ?

30

In particular, while praising the excellence of the three figures, ChвҖҷoe Hang took a different approach from Sin Sukchu by emphasizing Chinsan as the very site that nurtured the chЕҸnggi зІҫж°Ј вҖңrefined vital energyвҖқ manifested in their virtuous accomplishments and literary achievement, thereby reaffirming the significance of the book title Chinsan sego.

Following the prefaces written by Sin Sukchu and ChвҖҷoe Hang, ChЕҸng ChвҖҷangson proceeded to describe in turn the character and qualities of Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian. He wrote, вҖңWhen the source of water is deep, its flow is inevitably long; when the roots of a tree are deep, its branches and leaves are inevitably luxuriant. Their ancestors accumulated virtue and cultivated good fortune, and thus eminent ministers and great officials followed one after another.вҖқ

31 By this, he recalled that Kang HЕӯimaeng had at that time been appointed a meritorious subject and held high office, presenting this as evidence of

yЕҸgyЕҸng йӨҳж…¶ вҖңresidual blessings,вҖқ and underscored the transmission of both moral accomplishment and literary excellence within the family.

Although the three prefaces differed slightly from one another, they were, on the whole, similar to the standard prefaces found in literary collections, which typically assess an individualвҖҷs virtuous accomplishments and literary merits and describe the writerвҖҷs relationship to the subject. At the same time, in accordance with the distinctive character of sego, a compilation that brings together the writings of multiple members of a single lineage, they actively connected the family to its ancestral seat, praised the transmission of virtue and literary attainment across generations, and emphasized the importance of sustaining this legacy into the future.

Commemoration of a вҖңneglected talentвҖқ жҮ·жүҚдёҚйҒҮ and the Succession of the вҖңwill of forebearsвҖқ йҒәж—Ё

When Kang Yuhu, the seventh-generation descendant of Kang HЕӯimaeng, assumed office as Magistrate of ChвҖҷЕҸngju, he published Chinsan sego sokchip in 1658 (the 9th year of King HyojongвҖҷs reign). This sego brought together the writings of three figures: his great-grandfather Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, the fourth-generation descendant of Kang HЕӯimaeng; his grandfather Kang ChonggyЕҸng; and his uncle Kang Chinhwi. The volume included prefaces by yЕҸng tonnyЕҸngbusa пҰҙж•ҰеҜ§еәңдәӢ Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk, and chвҖҷЕҸmji chungchвҖҷubu sa еғүзҹҘдёӯжЁһеәңдәӢ ChЕҸng TugyЕҸng. In addition, although it was not ultimately included when the supplementary collection was printed, Pak ChangwЕҸn жңҙй•·йҒ (1612-1671), Magistrate of Sangju, also composed a preface at Kang YuhuвҖҷs request.

In his preface, Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk stated that, on the basis of Chinsan sego compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng, the literary achievement and moral accomplishments of the Chinsan lineage had long enjoyed renown in the world, and that their early and continued prosperity over successive generations had its clear origins. By contrast, regarding the supplementary collection, he expressed a sense of mourning and conveyed his relief that its publication had nonetheless been realized.

I spoke with solemn grief, saying: вҖңIf Heaven truly had no intention of producing men of talent, how could the Chinsan lineage have brought forth such individuals generation after generation? And if Heaven indeed intended for them to be born, how could an abrupt and premature death have resulted in such an end? Heaven bestowed ability, yet that ability could not be fully put to use; the remaining oil and lingering fragrance were left scarcely transmitted. How, then, could all of this be attributed solely to HeavenвҖҷs will? Is there not, perhaps, both fortune and misfortune bound up in this? Or is it that even a single branch of sandalwood is itself sufficient as a treasure, so abundance is not required? Fortunately, someone like you succeeded them, and so the work has been brought to publication today. Given all this, how could one claim that Heaven took no part at all in what unfolded between the beginning and the end?вҖқ

з«ҠжӮјд№Ӣжӣ°: вҖҳеӨ©иӢҘз„Ўж„Ҹж–јз”ҹжүҚ, дҪ•жҷүеұұд№Ӣдё–еҮәиӢҘжӯӨ, еӨ©жһңжңүж„ҸиҖҢз”ҹд№Ӣ, еүҮеҸҲдҪ•еҘ„еҝҪд№ӢиҮіжӯӨ? иҲҮд№ӢжүҚиҖҢдёҚ究其用, ж®ҳиҶҸиіёйҰҘ, е°ҷжңӘеӨҡеӮі, жӯӨиұҲзҡҶеӨ©д№Ӣж„Ҹд№ҹ? дәЎдәҰжңүе№ёдёҚе№ёеӯҳз„үиҖ…иҖ¶? жҠ‘ж ҙжӘҖдёҖжһқ, дәҰи¶ізҲІзҸҚ, дҪ•еҝ…еӨҡд№ҹ? е№ёжңүеҰӮдҪҝеҗӣиҖ…зҲІд№ӢеҫҢ, иғҪжў“иЎҢж–јд»Ҡж—Ҙ, иӢҘжҳҜиҖҢи¬Ӯд№ӢеӨ©жңӘе§ӢиҲҮж–је…¶й–“, еҸҜд№Һ?вҖҷ

32

Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk questioned the true intent behind HeavenвҖҷs seemingly dual attitude: bringing forth men of talent generation after generation yet not permitting their abilities to be fully realized. However, he ultimately consoled himself by attributing to Heaven the fact that even the small remnant of their writings, likened to the вҖңremaining oil and lingering fragrance,вҖқ had at least been preserved and transmitted. This stance stemmed from the reality that, although these figures were recognized by eminent contemporaries as men of talent, they did not attain high office and lived comparatively short lives.

Kang KЕӯksЕҸng studied under his maternal grandfather, Mojae ж…•йҪӢ Kim Anguk йҮ‘е®үеңӢ (1478-1543). After passing the civil service examination, he was granted

saga toksЕҸ иіңжҡҮи®Җжӣё вҖңendowed reading leave,вҖқ yet he ended his life at the age of fifty-one while serving as the

Еӯnggyo жҮүж•Һ вҖңfourth-rank advisorвҖқ in the

hongmunвҖҷgwan ејҳж–ҮйӨЁ вҖңoffice of special advisers.вҖқ Kang ChonggyЕҸng was well versed in Buddhist scriptures and the

Zhou yi е‘Ёжҳ“, and he earned recognition from Ugye зүӣжәӘ SЕҸng Hon жҲҗжёҫ (1535-1598). However, after suffering the consecutive losses of both parents, he died at the age of thirty-eight. Kang Chinhwi studied under SЕҸng Hon and received recognition from Paeksa зҷҪжІҷ Yi Hangbok жқҺжҒ’зҰҸ (1556-1618), but his official career concluded with his appointment as

pyЕҸlchwa еҲҘеқҗ вҖңthe fifth-rank assistant directorвҖқ at the age of thirty.

33 As their descendant, Kang Yuhu published

sego to preserve and transmit the limited amount of writing left behind by these men, writings that fell far short of their reputations. Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk inscribed this intention in his preface.

ChЕҸng TugyЕҸng, the

chokhyЕҸng ж—Ҹе…„ вҖңelder kinsmanвҖқ of Kang Yuhu, wrote his preface at Kang YuhuвҖҷs request. From a literary standpoint, he noted that Kang KЕӯksЕҸng enjoyed drinking and excelled at poetry to such a degree that King SЕҸnjo admired and took delight in his verses; that Kang ChonggyЕҸng displayed a poetic style close to that of Tang poetry е”җи©©; and that all those with whom Kang Chinhwi associated were

sabaek и©һдјҜ вҖңmasters of verse.вҖқ He further stated that вҖңin the Chinsan Kang lineage, from Kang Hoebaek onward, three generations had flourished in earlier times, and Kang KЕӯksЕҸng and Kang ChonggyЕҸng followed after them, so that the familyвҖҷs reputation continued for generations.вҖқ

34 With this ChЕҸng TugyЕҸng encouraged Kang Yuhu to follow in the footsteps of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng.

Pak ChangwЕҸn, who identified himself as a chokson ж—Ҹеӯ« вҖңdistant descendantвҖқ of Kang ChonggyЕҸng and Kang Chinhwi, took part, together with his friend Kim TЕӯksin йҮ‘еҫ—иҮЈ (1604-1684), in reviewing the manuscripts to some extent at Kang YuhuвҖҷs request. He eventually composed a preface as well. He first established the grounds for the existence of the supplementary collection by noting that, just as the Three So emerged from Misanзңүеұұ (C. Meishan) in China, so too had the Kang lineage in Chinsan, situated near Mount Turyu й ӯжөҒin the East, produced literary figures over successive generations. He also recounted several anecdotes concerning the writings of the three men.

Kang KЕӯksЕҸngвҖҷs

sijae и©©жүҚ вҖңpoetic talent,вҖқ as ChЕҸng TugyЕҸng also noted in his preface, was illustrated by the line вҖңThe great favor of the state I have yet to repay; following the lingering moonlight in my dream, I go alone to court in HeavenвҖқ зҸҚйҮҚеңӢжҒ©зҢ¶жңӘе ұ, еӨўе’Ңж®ҳжңҲзҚЁжңқеӨ©.

35 Pak ChangwЕҸn described how, because of this verse, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng received praise from King SЕҸnjo and was restored to office. He then compared this to the episode in which So Sik, while in exile, composed вҖңSujosaвҖқ ж°ҙиӘҝи©һ containing the words вҖңI only fear that in the jade-like palace where my lord resides, such lofty heights may not withstand the coldвҖқ еҸӘжҒҗз“ҠжЁ“зҺүе®Ү, й«ҳиҷ•дёҚеӢқеҜ’ and thereby had his punishment reduced.

36 He further mentioned Kang ChonggyЕҸngвҖҷs poem вҖңPaekchesЕҸngвҖқ зҷҪеёқеҹҺ and Kang ChinhwiвҖҷs вҖңYЕҸngmaeвҖқ и© жў…, noting that both were widely circulated and admired. At the same time, he revealed that men of such poetic talent were unable to fulfill their aspirations and passed away before they achieved their goals.

How deeply regrettable it is! Sir ChвҖҷwijuk [Kang KЕӯksЕҸng], in the middle years of his life, revealed his spiritual vitality and, resembling Mojae [Kim Anguk], gained renown from an early age. Together with Ko Chaebong, he rose side by side in the world of letters, yet suddenly the two of them were demoted. Not long after he was reinstated, he passed away with his aspirations still unfulfilled. Had Heaven granted him even a more time, who can know whether he might have sung the edifying virtue of a sagely ruler or followed the lingering resonance of the Qing court? Even if misfortune befell him, who could know whether, had he drafted a stirring proclamation dashed off by ChaebongвҖҷs brush, he might have subdued the unquenched momentum of the violent bandits? How could such things ever be measured?

зҚЁжғңд№Һ! йҶүз«№е…¬зӮійқҲж–јдёӯи‘ү, йЎҚйЎһд№Һж…•йҪӢ, иҡӨжӯІиңҡиӢұ. иҲҮй«ҳйңҪеіҜдёҰйЁ–ж–јж–ҮиӢ‘, дҝ„иҲҮд№ӢеҗҢж•—, ж•Қеҫ©жңӘд№…, йҪҺеҝ—жӯҝең°. е№ёиҖҢеӨ©еҒҮд№Ӣд»Ҙе№ҙ, еүҮжӯҢи© иҒ–еҢ–иҖҢиҝҪж·ёе»ҹд№ӢйҒәйҹі, еӣәдёҚеҸҜзҹҘ. йӣ–жҲ–дёҚе№ё, иҖҢиҚүйңҪеіҜеҘ®зӯҶд№ӢжӘ„, жӯ»ејәеҜҮжңӘжӯ»д№Ӣж°Ј, дәҰдҪ•еҸҜйҮҸд№ҹ?

37

As noted above, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng lost his father, Kang Pok е§ңеҫ© (1508-1529), at an early age and was raised and educated by his maternal grandfather Kim Anguk. Through this upbringing, he gained considerable reputation. However, when the powerful courtier Yi Ryang жқҺжЁ‘ (1519-1563) was expelled during the reign of King MyЕҸngjong, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng was implicated as part of Yi RyangвҖҷs faction. Together with figures such as Ko KyЕҸngmyЕҸng й«ҳ敬е‘Ҫ (1533-1592), he was forced to withdraw from office, remaining unable to return to government service for more than ten years. When he finally reentered official life, he passed away not long thereafter. Thus, unlike Ko KyЕҸngmyЕҸng, who composed the so-called вҖңMasang kyЕҸkmunвҖқ йҰ¬дёҠжӘ„ж–Ү with the outbreak of the Imjin War, circulated it throughout the provinces, and distinguished himself as a righteous army leader before falling in battle, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng had neither the opportunity to restore his honor nor the time to demonstrate his literary talent. Pak ChangwЕҸn also briefly mentioned the premature deaths of Kang ChonggyЕҸng and Kang Chinhwi, expressing his deep regret over the untimely loss of all three men.

Ah! When I consider the earlier worthies whose writings have been handed down in this sego, they all encountered the flourishing era in our dynasty and powerfully resounded with the prosperity of the state. As for the later worthies, although they were never able to unfold their aspirations to the fullest, their poetry nonetheless rose to great prominence. From this, the shifting course of fortune gives us ample reason to raise a heartfelt lament.

е—ҡе‘ј! дё–зЁҝд№ӢеӮі, з”ұеүҚж•ёе…¬, еүҮзҡҶеҖӨжң¬жңқдәЁеҳүд№Ӣжңғ, д»ҘеӨ§йіҙеңӢ家д№Ӣзӣӣ, иҖҢз”ұеҫҢж•ёе…¬, еүҮз¶ӯеҚ’дёҚж–Ҫ, д»ҘжҳҢе…¶и©©. ж–јжӯӨдәҰи¶ід»ҘиҰӢдё–йҒӢд№ӢжҺЁж•“, иҖҢзҷјеҗҫдәәд№ӢдёҖеҳ…д№ҹ.

38

Kang Hoebaek and Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, the main figures in original Chinsan sego, did not live entirely free of political turbulence. Kang HoebaekвҖҷs family experienced a crisis when his younger brother Kang Hoegye е§ңж·®еӯЈ (d. 1392), the son-in-law of King Kongyang of KoryЕҸ, was executed at the founding of ChosЕҸn. After the establishment of the new dynasty, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, the son-in-law of Sim On жІҲжә« (d. 1418), likewise faced a period in which he was compelled to withdraw from office. King TвҖҷaejongвҖҷs policy of curbing the influence of royal in-law families led to the execution of Sim On, who was the father-in-law of King Sejong. Moreover, Kang HЕӯian died at the comparatively early age of forty-eight, making it difficult to assert unequivocally that he вҖңencountered the flourishing era дәЁеҳү in our dynasty and powerfully resounded with the prosperity of the state.вҖқ Nevertheless, the explicit contrast drawn between the original collection and the supplementary collection can be understood as an effort to highlight more sharply the sense of regret and sorrow felt toward the individuals amid the political вҖңfortune and misfortuneвҖқ е№ёдёҚе№ё represented in the supplementary collection.

In this way, Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸkвҖҷs preface mentioned that the three figures in the supplementary collection were outstanding men who had continued the lineage over successive generations. He emphasized the fortunate aspect that, even amid the misfortune of not having been fully employed, their remaining writings could be transmitted to later generations through the publication of the supplementary collection. In ChЕҸng TugyЕҸngвҖҷs preface, focusing on anecdotes related to the three menвҖҷs literary works, he placed upon Kang Yuhu the dignity of a lineage that had produced writers generation after generation and presupposed its continuation into the future. In Pak ChangwЕҸnвҖҷs preface, he referred to the poetic talent of the three men and strongly asserted that they were unable to rise to high office and display their abilities, and even came to an early end. He further set forth this point as the distinction between the figures of the original collection and those of the supplementary collection, thereby revealing the meaning of publishing the supplementary collection.

Conclusion

Chinsan sego was compiled, like other family anthologies or collected works, to prevent poems and writings left by notable figures of previous generations from being lost to later generations. In particular, Chinsan sego holds significance as a pioneering collection, given its early publication in the ChosЕҸn period. It is also noteworthy that the title Chinsan sego continued to be used in publications throughout the ChosЕҸn period and even after KoreaвҖҷs liberation, underscoring its enduring value.

In June 2025, Chinsan sego held in the ChonвҖҷgyЕҸnggak Library of SЕҸnggyunвҖҷgwan University was designated a Tangible Cultural Heritage of Seoul. This appears to reflect recognition of its historical value: along with the Pak YЕҸngdon edition - a National Treasure-, Chinsan sego, preserved in ChonggyЕҸnggak as the first-edition lineage, was printed earlier. It also contains traces related to the literati purges following the death of Kim Chongjik. Through this as well, it may be said that Chinsan sego continues to maintain its classical value as a вҖңheritage.вҖқ

The purposes and intentions behind the compilation of Chinsan sego may be said to have been largely consistent while its publication continued over time. However, the work of classifying the various editions into distinct lineages has made it possible to identify more clearly the characteristics observable within each lineage, to grasp to some extent the contemporary circumstances and trends surrounding their publication, and to examine the compilation consciousness with greater precision. In this respect, it can be regarded as a meaningful undertaking.

In future research, I aim to identify similarities and differences in the philological features of sego by conducting comparative analyses with sego of other lineages, and thereby to outline the broader patterns and landscape of sego publication. Through this, I expect the findings to be meaningfully applied to the study of book production and circulation in the ChosЕҸn period.

Notes

Figure:

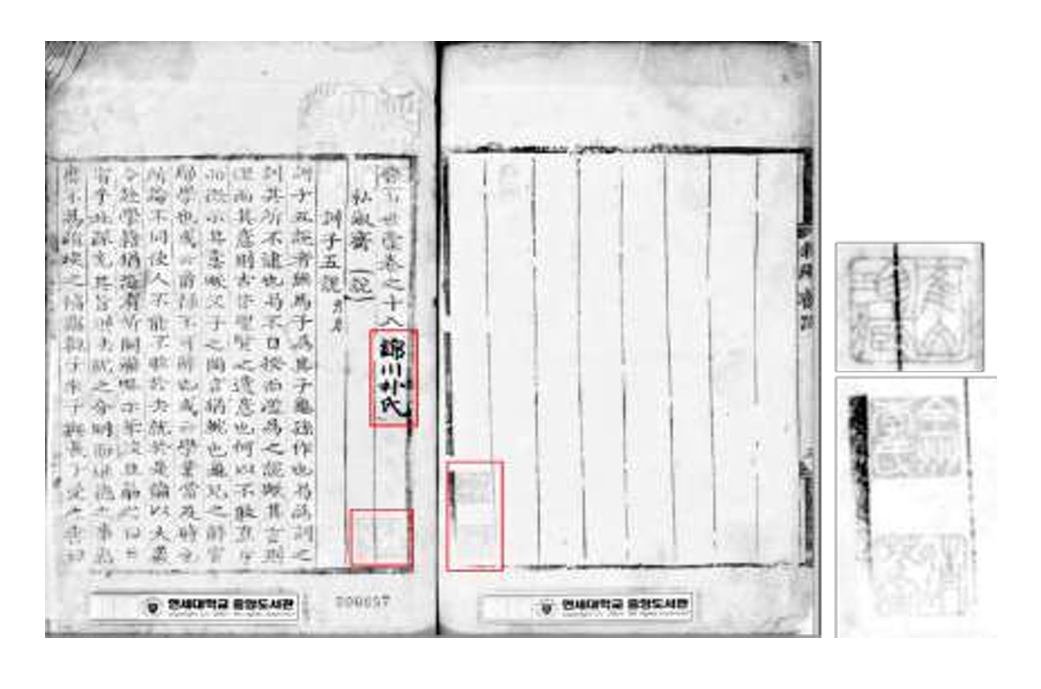

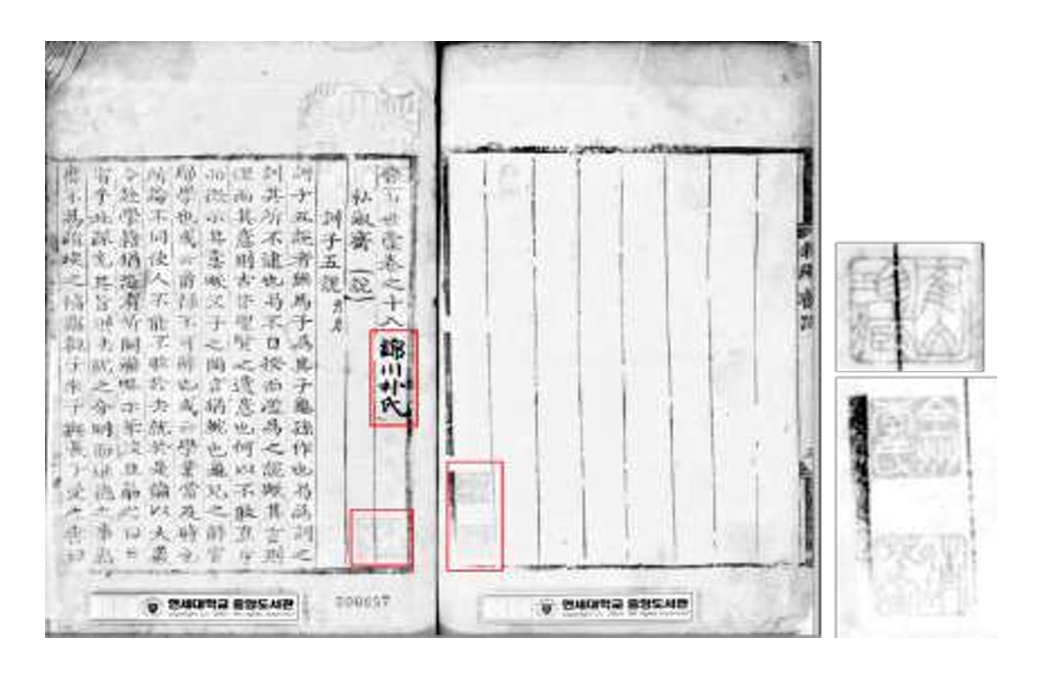

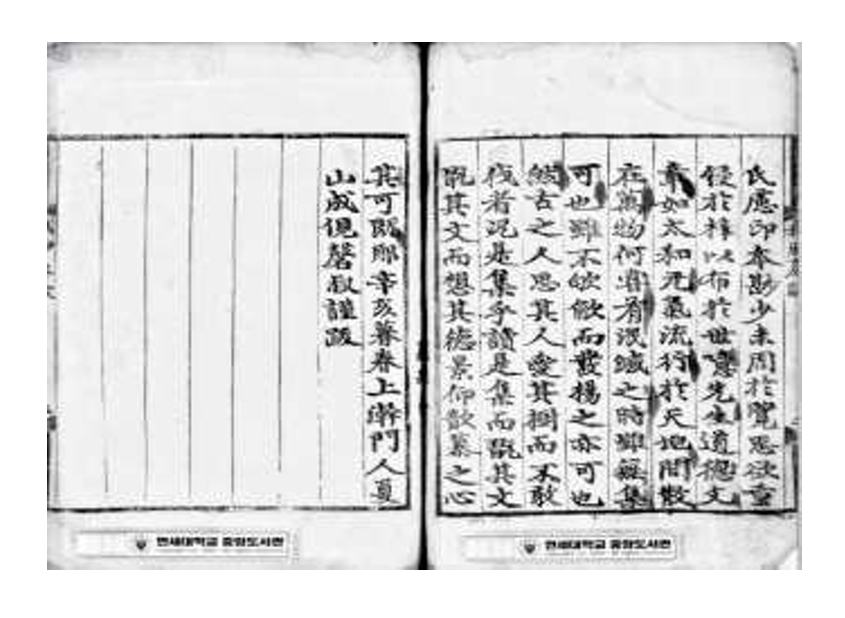

Chinsan sego, Pak YЕҸngdon edition (left) / Kyujanggak edition (right)

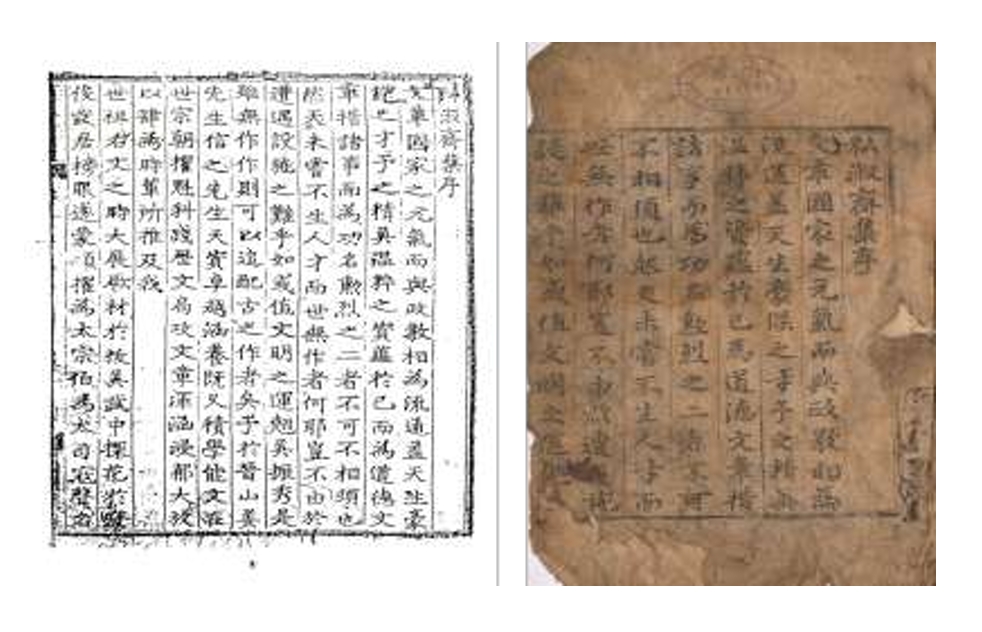

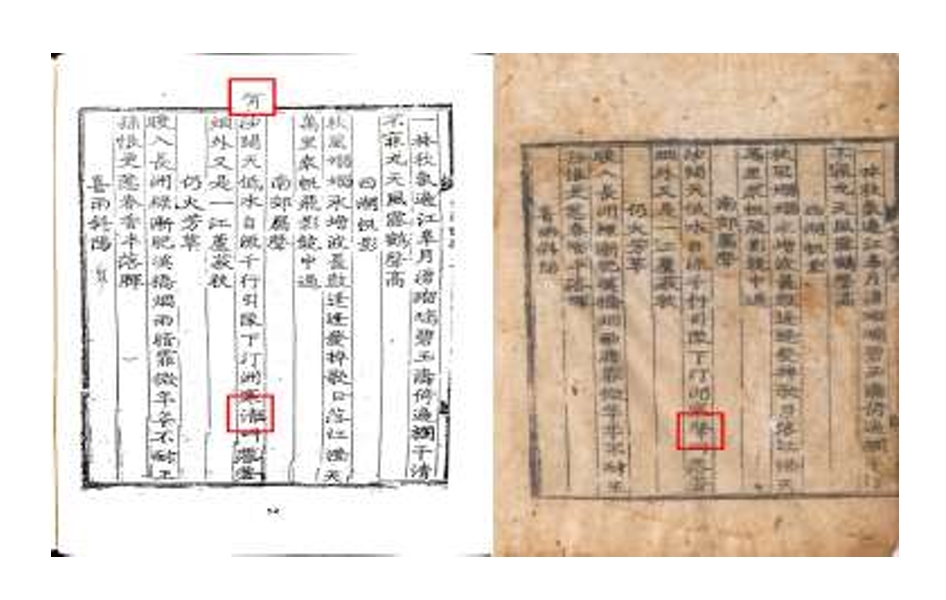

Figure:The YЕҸnse University edition of Chinsan sego (Sasukchaejip), the first leaf of the volume (left) and end page (right)

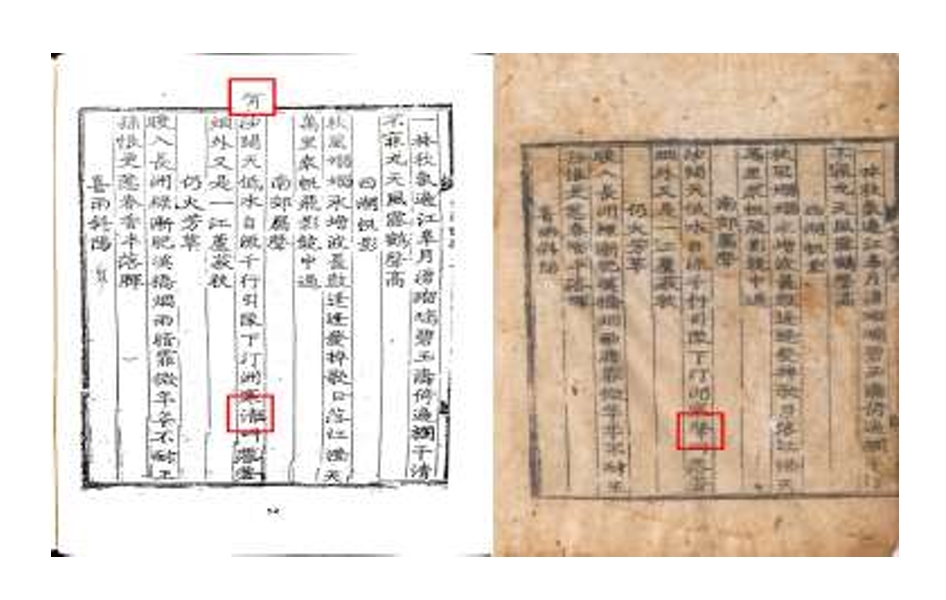

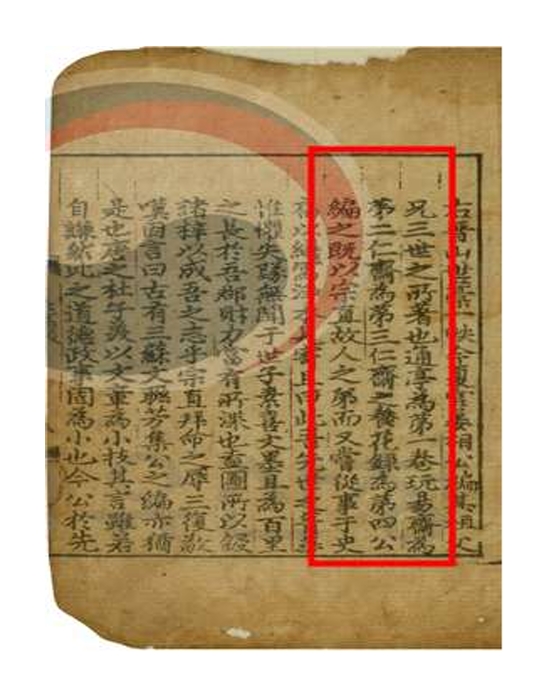

Figure:Preface of Sasukchaejip, Left: HЕҚsa Library edition of Sasukchaejip (first edition), Right: National Library of Korea edition of Chinsan sego (Sasukchaejip)

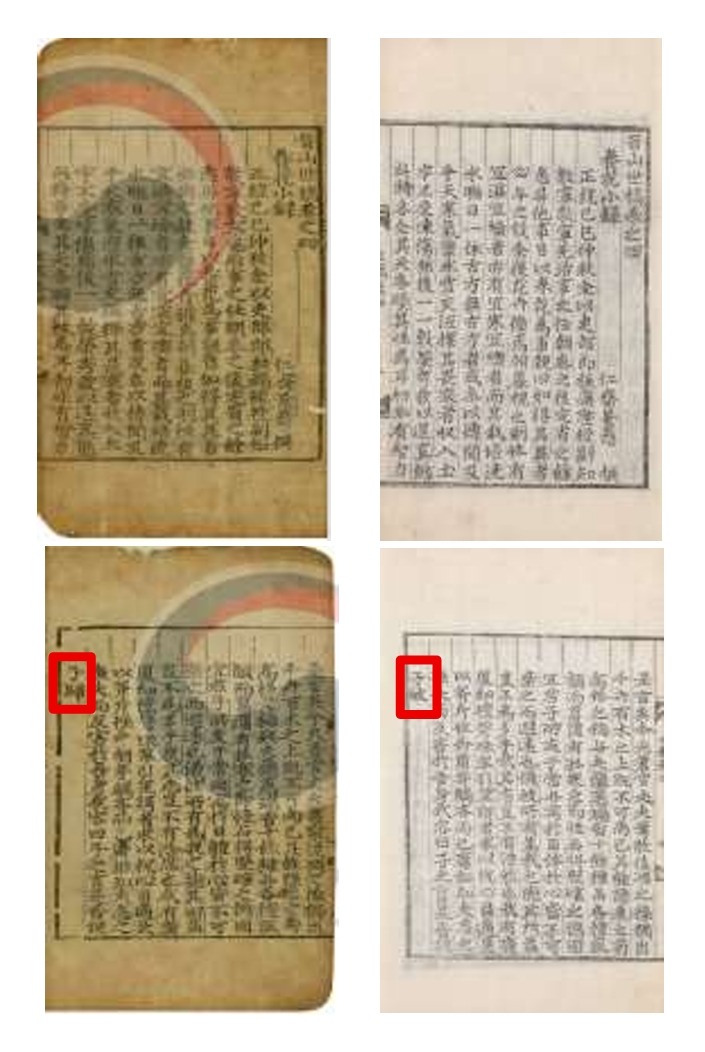

Figure:Postface of Chinsan sego (Sasukchaejip), Yonsei University edition

Figure:The HЕҚsa Library edition of Sasukchaejip (first edition, left) and the National Library of Korea edition of Chinsan sego (reprint of the first edition, right)

Figure:Kim ChongjikвҖҷs postscript in the Pak YЕҸngdon edition of Chinsan sego

|

Pak YЕҸngdon (1983) |

An IksЕҸng (2021) |

ChвҖҷoe KyЕҸnghun (2024) |

|

1474 (King SЕҸngjong 5) |

|

в—ҸWoodblock edition, 4 volumes in 1 fascicle. |

в—Ҹ Compiled by Kang HЕӯimaeng and Kim Chongjik (county magistrate) |

|

в—ҸChonвҖҷgyЕҸnggak (е°Ҡ經閣) Library edition at SЕҸnggyunвҖҷgwan University and National Library of Korea edition. |

в—Ҹ Woodblock edition, 4 volumes in 1 fascicle |

|

в—Ҹ Hamyang |

|

в—Ҹ Pak YЕҸngdon edition (National Treasure), etc. |

|

1476 (King SЕҸngjong 7) |

в‘ Woodblock edition |

|

|

|

в—Ҹ Postface by SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸng (жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝи·Ӣ) |

|

в—Ҹ Postface by Kang HЕӯimaeng (жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ移жҷүзү§и·Ӣ) |

|

1478 (King SЕҸngjong 9) |

|

в‘Ў Woodblock edition |

|

|

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle |

|

в—Ҹ Kyujanggak еҘҺз« й–Ј Library edition |

|

1483 (King SЕҸngjong 14) |

|

в‘ў Woodblock edition |

|

|

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle |

|

в—Ҹ National Library of Korea edition |

|

1491 (King SЕҸngjong 22) |

|

в‘ў Woodblock edition |

в—Ҹ In Kapchinja type, 17 volumes in 4 fascicles |

|

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle |

в—Ҹ Hanyang (reprint of the original edition) |

|

в—Ҹ ChвҖҷungnam University edition |

в‘ў Woodblock edition |

|

в—Ҹ 17 volumes in 4 fascicles |

|

в—Ҹ Unknown |

|

в—Ҹ ChвҖҷungnam University and National Library of Korea editions. |

|

Unknown (King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign) |

в—Ҹ Reprint of the first edition |

|

|

|

в—Ҹ Mansong Collection edition at KoryЕҸ University |

|

1653 (King Hyojong 4) |

в‘Ј Compiled by Kang Yuhu |

|

|

|

в—Ҹ Original Collection and Supplementary Collection |

|

в—Ҹ Total 8 volumes in 2 fascicles |

|

1658 (King Sukchong 11) |

|

в‘Ј Compiled by Kang Yuhu |

в‘Ј Compiled by Kang Yuhu |

|

в—Ҹ Woodblock edition |

в—Ҹ Woodblock edition (reprint of the original edition) |

|

в—Ҹ 8 volumes in 2 fascicles |

в—Ҹ His great-grandfather Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, grandfather Kang ChonggyЕҸng and uncle Kang Chinhwi-the literary works of these three ancestors were added as the Chinsan sego sokchip жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝзәҢйӣҶin four volumes and reprinted. |

|

в—Ҹ Kyujanggak Library edition |

|

Unknown (King YЕҸngjoвҖҷs reign) |

в‘Ө Woodblock movable type edition (жңЁжҙ»еӯ—жң¬) |

|

|

|

1805 (King Sunjo 5) |

|

в—Ҹ Compiled by Kang Chuhan |

в—Ҹ Woodblock movable type edition, 2 volumes in 1 fascicle |

|

в—Ҹ Woodblock movable type edition |

в—Ҹ Upper volume: Original Collection |

|

в—Ҹ 2 parts (дёҠдёӢ) in 1 fascicle |

в—Ҹ Lower volume: Five persons: Kang HЕӯimaeng, Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, Kang ChonggyЕҸng, Kang Chinhwi, and Kang Hangе§ңжІҶ |

|

в—Ҹ KyemyЕҸng University edition |

в—Ҹ At the end of the volume: Postfaces (1805) by Sim Yunji жІҲе…Ғд№Ӣ and Yun Haengjikе°№иЎҢзӣҙ (Magistrate of YЕҸnggwang) |

|

1845 (King HЕҸnjong 11) |

|

в‘Ө Compiled by Kang Kyuhoeе§ңеҘҺжңғ |

|

|

в—Ҹ Woodblock movable type edition |

|

в—Ҹ 5 volumes in 2 fascicles |

|

в—Ҹ Kyujanggak Library edition |

|

Unknown |

|

в‘Ө Woodblock movable type edition |

|

|

в—Ҹ 3 volumes in 1 fascicle |

|

в—Ҹ National Library of Korea and ChangsЕҸgak и—Ҹжӣёй–Ј Library editions |

|

Unknown |

|

в—Ҹ Transcription edition |

|

|

в—Ҹ 1 fascicle (complete in 4 volumes in 1 fascicle) |

|

в—Ҹ National Library of Korea edition |

|

Unknown (19th century) |

|

|

в‘Ө Compiled by Kang Kyuhoe |

|

в—Ҹ Woodblock movable type edition |

|

в—Ҹ 5 volumes in 2 fascicles |

|

в—Ҹ Kyujanggak Library and National Library of Korea editions |

|

1959 |

в—Ҹ Lithographic edition (зҹізүҲжң¬) |

|

|

|

Category |

Edition Type |

Publication Details |

Features |

|

The first edition (1474 edition) |

Woodblock edition |

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle |

в—Ҹ Includes Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs вҖңChinsan sego i Chinmok palвҖқжҷүеұұдё–и—Ғ移жҷүзү§и·Ӣand SЕҸ KЕҸjЕҸngвҖҷs вҖңChinsan sego palвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝи·Ӣ |

|

в—Ҹ Single-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘Ёе–®йӮҠ) |

|

в—Ҹ 11 lines with 19 characters per line |

|

в—Ҹ Small black punctuation marks (е°Ҹй»‘еҸЈ) |

в—Ҹ Two editions exist: the Pak YЕҸngdon edition and the KoryЕҸ University edition (л§ҢмҶЎ иІҙ 408) |

|

в—Ҹ Inward-facing black fish-tail marks at the top and bottom (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

|

1491 edition |

Woodblock edition |

в—Ҹ 1 fascicle (complete in 17 volumes, 4 fascicles): |

в—Ҹ Consists of the first edition of Kang HЕӯimaengвҖҷs Sasukchaejip |

|

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

|

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

в—Ҹ Includes a preface by SЕҸng HyЕҸn жҲҗдҝ” |

|

в—Ҹ 12 lines with 19 characters per line |

|

в—Ҹ Black mouth marks at the top and bottom (дёҠдёӢй»‘еҸЈ) |

|

в—Ҹ Inward-facing black fish-tail marks at the top and bottom (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

|

1658 edition |

Woodblock edition |

в—Ҹ 8 volumes in 2 fascicles (original collection: 4 volumes; supplementary collection: 4 volumes): |

в—Ҹ The supplementary collection was published by Kang Yuhu е§ңиЈ•еҫҢ (1606-1666), great-grandson of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng е§ңе…ӢиӘ (1526-1576) |

|

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Includes the poetry and prose of three generationsвҖ”Kang KЕӯksЕҸng, Kang ChonggyЕҸng, and Kang Chinhwi |

|

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

в—Ҹ Includes prefaces by Yi KyЕҸngsЕҸk and ChЕҸng TugyЕҸng |

|

в—Ҹ 11 lines with 19 characters per line |

|

в—Ҹ Inward-facing floral fish-tail marks at top and bottom (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘иҠұзҙӢйӯҡе°ҫ) (varied) |

|

1845 edition |

Woodblock movable type edition |

в—Ҹ 3 volumes in 1 fascicle: |

в—Ҹ Published under the direction of Kang Kyuhoe е§ңеңӯжңғ, the thirteenth-generation descendant of Kang HЕӯimaeng. |

|

в—Ҹ Single-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘Ёе–®йӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Does not include Yanghwa sorok (Kim ChongjikвҖҷs postscript does not contain the phraseд»ҒйҪҠд№ӢйӨҠиҠұйҢ„еҜ«з¬¬еӣӣ) |

|

в—Ҹ 10 lines with 20 characters per line |

в—Ҹ Does not include the poetry and prose of Kang SЕҸktЕҸk |

|

в—Ҹ Inward-facing floral fish-tail marksвҖ”three at the top and two at the bottom (дёҠдёүи‘үдёӢдәҢи‘үе…§еҗ‘иҠұзҙӢйӯҡе°ҫ) |

в—Ҹ Includes the poetry and prose of Kang TЕҸkpu (a fifth-generation descendant of Kang KЕӯksЕҸng), Kang Chuje, Kang Chunam, and Kang ChЕҸnghwan. |

|

в—Ҹ Includes a postface by Kim Sangjik йҮ‘зӣёзЁ· (1779-1851) |

|

в—Ҹ Includes вҖңChinsan Kangssi sego puingnokвҖқ жҷүеұұе§ңж°Ҹдё–зЁҝйҷ„зӣҠйҢ„ [Supplementary Records to the Chinsan Kang ClanвҖҷs Family Anthologies] |

|

1959 edition |

Lithographic edition (зҹіеҚ°жң¬) |

в—Ҹ 3 volumes in 1 fascicle: |

в—Ҹ Published under the direction of Kang Taegon, a descendant of Kang SЕҸktЕҸk |

|

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Published together with Kang ChunghЕӯi (descendant of Kang ChongdЕҸk, the eldest son of Kang Hoebaek), Kang YЕҸwЕҸn (descendant of Kang UdЕҸk, the second son of Kang Hoebaek), and Kang Chun (descendant of Kang ChindЕҸk, the third son of Kang Hoebaek) |

|

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

|

в—Ҹ 10 lines with 20 characters per line |

в—Ҹ Includes a postface by Kang Taegon (intermediate edition) |

|

в—Ҹ Inward-facing black fish-tail marks at the top (дёҠе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

в—Ҹ Includes only the classical Chinese poems of Kang Hoebaek, Kang SЕҸktЕҸk, and Kang HЕӯian from the original collection (Does not include Yanghwa sorok) |

Table.Holdings of the Chinsan sego Kapchin Edition (woodblock reprint) in Korea

|

National Library of Korea Edition |

YЕҸnse University Edition |

ChвҖҷungnam University Edition |

|

Edition |

Woodblock print (reprint in the Kapchin type) |

|

Publication Information |

[Chinju] Kang Kwison е§ңйҫңеӯ«, [the 22nd year of King SЕҸngjongвҖҷs reign (1491)] |

|

Physical Description |

в—Ҹ 5 volumes in 1 fascicle (partial copy): |

в—Ҹ 2 volumes in 1 fascicle (70 leaves, partial copy) |

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle (partial copy) |

в—Ҹ 4 volumes in 1 fascicle (partial copy) |

|

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Single-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘Ёе–®йӮҠ) |

в—Ҹ Double-border frame on all four sides (еӣӣе‘ЁйӣҷйӮҠ) |

|

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

в—Ҹ Half-frame layout (еҚҠйғӯ) |

|

в—Ҹ 19.2 Г— 13.8 cm, ruled (жңүз•Ң) |

в—Ҹ 19.5 Г— 14.4 cm, ruled (жңүз•Ң) |

в—Ҹ 20.2Г—14.4 cm, ruled (жңүз•Ң) |

в—Ҹ 19.6Г—14.3 cm, ruled (жңүз•Ң) |

|

в—Ҹ 12 lines and 19 characters per line |

в—Ҹ 12 lines and 19 characters per line |

в—Ҹ 12 lines and 19 characters per line |

в—Ҹ 12 lines and 19 characters per line |

|

в—Ҹ Upper and lower black punctuation marks (дёҠдёӢй»‘еҸЈ) |

в—Ҹ Black punctuation marks (й»‘еҸЈ) |

в—Ҹ Large upper and lower black punctuation marks (дёҠдёӢеӨ§й»‘еҸЈ) |

в—Ҹ Small upper and lower black punctuation marks (дёҠдёӢе°Ҹй»‘еҸЈ) |

|

в—Ҹ Upper and lower inward-facing black fishtail marks (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

в—Ҹ Inward-facing black fishtail marks (е…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

в—Ҹ Upper and lower inward-facing black fishtail marks (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

в—Ҹ Upper and lower inward-facing black fishtail marks (дёҠдёӢе…§еҗ‘й»‘йӯҡе°ҫ) |

|

в—Ҹ Overall size 28.5Г—18.8 cm |

в—Ҹ Overall size 27.8Г—18.5cm |

в—Ҹ Overall size 30 cm |

в—Ҹ Overall size 29.3Г—18.6cm |

|

Notes |

вҒғ Title on the text block (зүҲеҝғйЎҢ): Sego (дё–зЁҝ) |

вҒғ Title (иЎЁйЎҢ): Chinsan sego (жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ) |

вҒғ Title on the text block (зүҲеҝғйЎҢ): Sego (дё–и—Ғ) |

вҒғ Title on the text block (зүҲеҝғйЎҢ): Sego (дё–и—Ғ) |

|

вҒғ Preface: зҷёеҚҜйҮҚдёғ(1483.7.7.) йҒ”еҹҺеҫҗеұ…жӯЈеүӣдёӯжӣё |

вҒғ Title on the text block (зүҲеҝғйЎҢ): Sego (дё–и—Ғ) |

вҒғ Colophon at the end of the volume (еҚ·жң«): иҫӣдәҘ(1491)жҡ®жҳҘжңүж—Ҙй–ҖдәәеӨҸеұұзЈ¬еҸ”(жҲҗдҝ”)謹и·Ӣ |

вҒғ Colophon at the end of the volume (еҚ·жң«): иҫӣдәҘ(1491)жҡ®жҳҘжңүж—Ҙй–ҖдәәеӨҸеұұзЈ¬еҸ”(жҲҗдҝ”)謹и·Ӣ |

|

вҒғ Seals: зү©еҪўй»‘еҚ° 2 йЎҶ (еҚ°ж–ҮжңӘи©і) |

вҒғ Compilation order (з·Ёж¬Ў): Chinsan sego volumes 12-13 (corresponding to Sasukchaejip first edition, vols. 8-9; 14 leaves of вҖңNongguвҖқ иҫІи¬і are missing) |

вҒғ Seals: еҜүеұұзҸҚи—Ҹ(еҚ·йҰ–), е…Ёе·һп§Ўж°Ҹ(еҚ·жң«), ж·ёиҠ¬е®Ө(еҚ·жң«) |

вҒғ Missing leaves (пӨҳејө): 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b |

|

вҒғ Compilation order (з·Ёж¬Ў): Chinsan sego volumes 5-9 (corresponding to Sasukchaejip first edition, vols. 1-5) |

вҒғ Manuscript notes (еўЁжӣё): йҢҰе·қжңҙж°Ҹ(еҚ·йҰ–) |

вҒғ Compilation order (з·Ёж¬Ў): Sego volumes 18-21 (corresponding to Sasukchaejip first edition, vols. 14-17) |

|

вҒғ Compilation order (з·Ёж¬Ў): Sego volumes 18-21 (corresponding to Sasukchaejip first edition, vols. 14-17) |

|

Call Number |

еҸӨ3648-00-104 |

еҸӨ3648-00-106 |

кі м„ң(к·Җ) 233 0 |

йӣҶ.зёҪйӣҶйЎһ-йҹ“еңӢ-221 |

Reference List

- An IksЕҸng м•Ҳмқөм„ұ. вҖңChosЕҸn sidae sego Еӯi kanhaengyangsang kwa tвҖҷЕӯkchingвҖқ мЎ°м„ мӢңлҢҖ дё–зЁҝмқҳ еҲҠиЎҢм–‘мғҒкіј нҠ№м§•. MA thesis., The Academy of Korean Studies, 2021.

- ChвҖҷoe KyЕҸnghun мөңкІҪнӣҲ. вҖңChosЕҸn chЕҸnвҖҷgi sego Еӯi kanhaeng kwa pвҖҷanbonвҖқ мЎ°м„ м „кё° дё–зЁҝмқҳ к°„н–үкіј нҢҗліё. SЕҸjihak yЕҸnвҖҷgu жӣёиӘҢеӯёзЎҸ究 97 (2024): 83-106.

- Kang HЕӯimaeng е§ңеёҢеӯҹ. Sasukchaejip з§Ғж·‘йҪӢйӣҶ (йҮҚеҲҠжң¬). Manuscript held at Hangukhak chungang yЕҸnвҖҷguwon ChangsЕҸgak, shelfmark K4-6092.

- Kang SЕҸngchвҖҷang к°•м„ұм°Ҫed. Chinsan sego жҷӢеұұдё–зЁҝ (еҪұеҚ°жң¬). Seoul: SinyЕҸngsa, 2011a.

- _____. (ChЕӯngbogugyЕҸk) Chinsan sego (мҰқліҙкөӯм—ӯ) 진мӮ°м„ёкі . Seoul: SinyЕҸngsa, 2011b.

- Kang SЕҸnggyu к°•м„ұк·ң. вҖңSasukchae Kang HЕӯimaeng sanmun yЕҸnвҖҷguвҖқ з§Ғж·‘йҪӢ е§ңеёҢеӯҹ ж•Јж–Ү зЎҸ究. Ph.D. thesis., Korea University, 2024.

- Ku Chahun кө¬мһҗнӣҲ. вҖңChosЕҸnjo Еӯi changsЕҸin В· changsЕҸga yЕҸnвҖҷgu: KoryЕҸ taehakkyo sojangbon Еӯl taesang ЕӯroвҖқ жңқй®®жңқмқҳ и—ҸжӣёеҚ°гҶҚи—Ҹжӣёе®¶ зЎҸ究: кі л ӨлҢҖн•ҷкөҗ мҶҢмһҘліёмқ„ лҢҖмғҒмңјлЎң. Ph.D. diss., Korea University, 2011.

- Pak YЕҸngdon л°•мҳҒлҸҲ. вҖңChisan sego chвҖҷopвҖҷanbon kuip chЕҸnmalвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝеҲқзүҲжң¬иіје…ҘйЎҡжң«. SangsЕҸ е°ҷжӣё 5 (1983): 9-11.

- Sim Ujun мӢ¬мҡ°мӨҖ. вҖңChinsan sego sagwЕҸnhappon Еӯi chemunjeвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ еӣӣеҚ·еҗҲжң¬мқҳ и«ёе•ҸйЎҢ. SЕҸjihak yЕҸnвҖҷgu жӣёиӘҢеӯёзЎҸ究 18 (1999): 103-114.

- Sin SЕӯngun мӢ мҠ№мҡҙ. вҖңSЕҸngjongjo munsayangsЕҸng kwa munjippвҖҷyЕҸnвҖҷganвҖқ жҲҗе®—жңқ ж–ҮеЈ«йӨҠжҲҗкіј ж–ҮйӣҶз·ЁеҲҠ. HanвҖҷguk munhЕҸn chЕҸngbo hakhoeji н•ңкөӯл¬ён—Ңм •ліҙн•ҷнҡҢм§Җ 28 (1995): 301-390.

- Yi Chongmuk мқҙмў…л¬ө. Chinsan sego haeje 진мӮ°м„ёкі н•ҙм ң.

- Yi InyЕҸng жқҺд»ҒжҰ®. ChвҖҷЕҸngbunsil sЕҸmok ж·ёиҠ¬е®Өжӣёзӣ®. Seoul: PoyЕҸnвҖҷgak, 1968.

- Yi UsЕҸng мқҙмҡ°м„ұ ed. Sasukchaejip з§Ғж·‘йҪӢйӣҶ (мҙҲк°„ліё м„ңлІҪмҷёмӮ¬ н•ҙмҷёмҲҳмқјліё) vol.3. SЕҸngnam: Asea munhwasa, 1992.

- Yu PвҖҷungyЕҸn мң н’Қм—°. вҖңChinsan sego sogoвҖқ жҷүеұұдё–зЁҝ е°ҸиҖғ. Hancha Hanmun kyoyuk жјўеӯ—жјўж–Үж•ҺиӮІ 9 (2002): 253-286.

- _____. вҖңChisan sego haejeвҖқ 진мӮ°м„ёкі н•ҙм ң. In (ChЕӯngbogugyЕҸk) Chinsan sego (мҰқліҙкөӯм—ӯ) 진мӮ°м„ёкі . Seoul: SinyЕҸngsa, 2010.

- Yun Hojin мңӨнҳём§„. HabЕҸdЕӯ YenchвҖҷing tosЕҸgwan sojang sego haejejip н•ҳлІ„л“ңмҳҢм№ӯлҸ„м„ңкҙҖ мҶҢмһҘ дё–зЁҝ н•ҙм ң집. Seoul: MinsogwЕҸn, 2021.