Abstract

This paper applies a stratigraphic analytical method to the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ ń║öŔíîň┐Ś chapter of the Han shu Š╝óŠŤŞ and uses the results of this analysis to argue that the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is a composite text. The contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ reflect three major moments of authorship: a catalogue composed by Western Han scholar Dong Zhongshu ŔĹúń╗▓Ŕłĺ (179-104 BCE) that summarizes anomalies and calamities recorded in the Chunqiu Šśąšžő ÔÇťSpring and Autumn AnnalsÔÇŁ; a catalogue composed by Western Han scholar Liu Xiang ňŐëňÉĹ (77-6 BCE) that expanded Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs list and applied the Hong fan Wuxing zhuan Š┤¬š»äń║öŔíîňé│ theoretical framework to it; and Ban GuÔÇÖs šĆşňŤ║ (32-92) fusion of these two catalogues and addition of a catalogue of Western Han anomalies to form the main part of the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ This view of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as a composite text breaks away from the traditional focus on whether it reflects a tendentious view of history and the extent to which its contents were fabricated, demanding that before such questions be asked, the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ must first be studied by its constituent layers. Indeed, stratigraphic analysis suggests that the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ reflect acts of rigorous historical study (not intentional deceipt or fabrication) carried out from the theoretical perspective of ÔÇťheaven-human sentient response theoryÔÇŁ ňĄęń║║ŠäčŠçëŔźľ at separate points in time) and thus revitalizes this text as a source of Han intellectual history.

-

Keywords: ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ ń║öŔíîň┐Ś, Han shu Š╝óŠŤŞ, stratigraphic textual analysis, heaven-human sentient response theory ňĄęń║║ŠäčŠçëŔźľ

Introduction: The ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ and Obstacles to Reading It

An Unfortunately Misrepresented Text

Few Sinographic texts that emerged in early imperial China have been more misunderstood (and more deeply misconstrued) than the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ ń║öŔíîň┐Ś (Five Elements Treatise) chapter of Eastern Han (25-220 BCE) scholar Ban GuÔÇÖs šĆşňŤ║ (ca. 32-92 CE) Han shu Š╝óŠŤŞ (Documents of the Han). Some of this has to do with the recondite and idiosyncratic view of the world that it presents: its view is not readily comprehensible without an understanding of early Chinese material philosophy; and even when comprehended, it is a view that is so distant from a modern scientific understanding of the physical world that recent observers have been led to dismiss it as being a kind of hocus pocus invented by disingenuous schemers of the Han court to deceive gullible wielders of political power. This has led to an unfortunate overlooking of this very important text of Han dynasty political philosophy.

Written as one of the zhi ň┐Ś ÔÇťtreatiseÔÇŁ chapters of the Han shu, the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is essentially a catalogue of anomalies that were recorded as having occurred in history across a range of time spanning from the earliest days of historiographical memory in the era of legendary kings Yao ňá», Shun Ŕłť, and Yu šŽ╣ to the late Western Han (202 BCE-9 CE). Most of these anomalies are events in nature; these include droughts, blizzards, fires, strange pandemics, birth deformities, and odd behavior in animals. A small number are freak incidents that happen within human society, like a bizarre incident involving an intruder in the Han palace, strange occurrences that were recorded as having happened when important rites were being carried out, and unusual fashion trends.

The ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ analyzes these incidents using a theoretical framework based on the idea that human action radiates out into the material world. This is not simply because humans, being physical beings, can interact directly with the physical world, but because, according to the view of this framework, human action, and particularly that of political rulersÔÇöthe

wang šÄő ÔÇťkingsÔÇŁ of Shang and Zhou dynasty history, the

zhu hou ŔźŞńż» ÔÇťmany vassalsÔÇŁ of the Zhou realm, the

jun zhu ňÉŤńŞ╗ ÔÇťnoble sovereignsÔÇŁ described in Warring States political theory, and the

huang di šÜçňŞŁ ÔÇťaugust thearchsÔÇŁ of the Han dynastyÔÇöhas a moral valence that influences the very fabric of the physical world. According to this framework, virtuous political action leads to harmony and balance in nature (expressed through the regular procession of the seasons and propitious conditions for agricultural production), whereas corrupt behavior creates disruption and imbalance (manifest in extreme, damaging weather and bizarre events). The material mechanism that links the material environment to human behavior is the properties of the

qi Š░ú ÔÇťvaporsÔÇŁ of the five elementsÔÇö

tu ňťč ÔÇťearth,ÔÇŁ

mu ŠťĘ ÔÇťwood,ÔÇŁ

huo šüź ÔÇťfire,ÔÇŁ

jin ÚçĹ ÔÇťmetal,ÔÇŁ and

shui Š░┤ ÔÇťwaterÔÇŁÔÇöand the behavior of

yin ÚÖ░ and

yang ÚÖŻ, which are described in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as being sensitive to the moral actions of human political leaders.

1

This theory is articulated in the pre-Han (possibly early Warring States period) text of the

Hong fan Š┤¬š»ä (Vast Pattern) and its (circa early Western Han) exegesis, the

Hong fan Wuxing zhuan Š┤¬š»äń║öŔíîňé│ (Five Elements Commentary to the Vast Pattern); the logical framework of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is taken directly from those two works.

2 While Ban Gu does not explicitly assert that this theory is an accurate description of physical reality, the

Han shu catalogue of historical anomalies presents strange events from recorded history and analyzes these using the theory, attributing their causes to corrupt political behavior. The

Han shu is thus the cataloguing of human history from the perspective of this theory in which the moral aspect of human behavior influences the material environment.

Barrier Number 1: Foreignness of Its Conceptual View

Needles to say, this theoretical viewÔÇöan integration of material and political philosophyÔÇöis foreign to both modern physical and political science and is thus difficult to analyze from the view of these disciplines. While it has been thoroughly observed and documented in academic literature in East Asian languages, where a particular vocabulary has developed to describe it, English language scholarship has not yet produced an apt terminology to describe the theoretical view presented in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ Terms like ÔÇťomenologyÔÇŁ (since the corruption that causes anomalies is often linked to later political downfall and social chaos) and ÔÇťcorrelative cosmologyÔÇŁ have been used; but the latter term does not occur as part of the discourse that expounded this view of anomalies in Han texts like the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ; and the term ÔÇťomenÔÇŁ only describes one aspect of this view and is not comprehensive. Analytical language used in East Asian scholarship does a better job of describing this way of thinking. In Chinese scholarship, one common term is

zaiyi lilun šüŻšĽ░šÉćŔźľ (theory of calamities and wondrously odd occurrences)

3; in Korean literature, there is the descriptive term

ch┼Ćnin kam┼şngnon ňĄęń║║ŠäčŠçëŔźľ (heaven-human sentient response theory);

4 and in Japanese, the term is

tenjin s┼Źkanron ňĄęń║║šŤŞÚľóŔźľ (heaven-human interrelation theory).

5 (In the latter two terms, ňĄę ÔÇťheavenÔÇŁ refers to a kind of sentience that is immanent in nature and responsive to the moral values of human action through the material mechanisms of nature: this concept informs the theory of historical anomalies expressed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ)

Barrier Number 2: Uncertainty of Authorship

Apart from the view expressed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ being so foreign to a modern view of material and political philosophy, discussion of the text itself has been complicated by uncertainty with regard to how it was compiled. Since the Yiwen

zhi ŔŚŁŠľçň┐Ś (Treatise on Arts and Letters) chapter of the

Han shu was based on Western Han scholar Liu XiangÔÇÖs ňŐëňÉĹ (77-6 BCE) inventory of manuscripts that had been collected as part of an imperial project to gather together the books of the realm (as Ban Gu himself tells in his preface to the

Yiwen zhi), some scholars have speculated that Liu Xiang similarly authored the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ (or at least some significant part of it); others have proposed that some other, indeterminable individual (or individuals) may have contributed to its contents in the Western or early Eastern Han period.

6 This uncertainty has meant that if the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is to be taken as a source of Han dynasty intellectual history, then it cannot be determined whose intellectual history it is representing. Is it that of Ban Gu writing in the Eastern Han? Or Liu Xiang writing in the late Western Han? Or some other author? Such uncertainty daunts attempts to analyze its contents and put them together with what we know of Han dynasty history and thought.

Barrier Number 3: The Possibility that Its Contents are a Fabrication

Added to these two challenges to reading the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ (the foreignness of its contents and the uncertainty of its authorship) is the skepticism that some have expressed with regard to the historical veracity of the events it records. German-American scholar Wolfram Eberhard (1909-1989) has perhaps been the most strident in his critique. Eberhard as a doctoral student at Berlin University observed in his 1933 doctoral dissertation, titled

Beitr├Ąge zur kosmologischen Spekulation der Chinesen der Han-Zeit (Contributions to Chinese Cosmological Speculation in the Han Period), that the dates of many (15) of the solar eclipses recorded in the

Han shuÔÇÖs ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ and

Ben ji ŠťČš┤Ç (Basic Annals) chapters as occurring in the Western Han period (54 in total) do not line up with the list of solar eclipses visible in the Western Han that can be derived by mathematical means.

7 Conversely, several eclipses (23) that are mathematically verifiable as having occurred in the Western Han and that would have been clearly visible at the time were not recorded in the

Han shu.

8 In order to interpret these discrepancies, Eberhard reasoned from the idea that in the Han period, eclipses (and other like anomalous events) were open to being used as the basis for political critique. On this premise, he proposed that recorders and historians who created and maintained records of the Western Han recorded only those eclipses that were needed to serve as ammunition for political critique of despised leaders. The same recorders and historians also (either contemporaneously or retrospectively) inserted false accounts of eclipses into the historical record in order to asperse emperors and officials whom they wished to criticize.

9

Who exactly it was Eberhard believed was in control of the writing of the history of anomaliesÔÇöomitting eclipses when irrelevant to political critique and inserting false records of eclipses into the historic record when neededÔÇöand in what time frame with regard to the events portrayed in the

Han shu is not clear from his dissertation. In other articles by Eberhard published the same year (1933), he called attention to Liu Xiang and his son, Liu Xin ňŐ늺ć (d. 23 CE), claiming that it could be proven that they had inserted records of eclipses that never happened into the classic texts that they had putatively edited (namely, the

ChunqiuŠśąšžő and its

Zuo zhuan ňĚŽňé│ and

Guliang zhuan šęÇŠóüňé│ commentaries).

10 In his dissertation, Eberhard also claimed that Liu Xin had edited the

Chunqiu record of eclipses.

11 Likely, when he wrote his dissertation, Eberhard suspected that similar intentional falsifications had been retrospectively inserted into historical records containing accounts of the Western Han by Liu Xiang and Liu Xin, and that historical records on anomalies for the Western Han period had in general been edited by them to reflect their political views. Eberhard certainly came to believe that the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ itself had been copied more or less

in toto from a text that had been compiled by Liu Xiang and Liu Xin.

12

EberhardÔÇÖs critique of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ has colored the views of scholars writing in English ever since. While some of anomalies catalogued in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ are obviously suspect (such as a small number of accounts of revenant dead), for the majority of events (such as earthquakes, fires, severe weather, strange behavior in animals, etc.), there is nothing in the events themselves (such as supernatural details) that makes them a priori impossible. However, if it could be shown by mathematical proof that the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ record of eclipses was a partially fabricated record created for contemporary political or historical critique, was it not then the case that the same judgment of inaccuracy and false tendentiousness should be applied to all of its contents? From this proposition, it follows that if the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is a false record of history meant to be used as a tool of political critique by Liu Xiang and Liu Xin, then it is an idiosyncratic view of history indeed, and becomes more of a curiosity than an important source of history (including intellectual history).

Admittedly, not all readers of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ have been as dismissive. In the critical material attached to his translation of the

Han shu (published in three volumes between 1938 and 1955), American sinologist Homer Dubs (1892-1969) made observations similar to those of Eberhard, but with critical differences in his interpretation of the data. Writing in 1938, Dubs described how he performed a similar comparison of actual, mathematically verifiable solar eclipses with those recorded in the

Han shu. Dubs found that ÔÇťthe Chinese accounts are predominatingly reliable, even for the beginning of the Han period.ÔÇŁ

13 Like Eberhard, Dubs also observed a number of discrepancies between the actual record of eclipses and the

Han shu record. Some eclipses that did occur were not recorded, and several eclipses that did not actually occur appear in the record.

14 Also like Eberhard, Dubs proposed that the political significance of actual eclipses had an influence on whether or not they were recorded: ÔÇťeclipses were considered as warnings to the ruler from Heaven, so that during an unpopular reign all visible eclipses were recorded, while during a decade in a ÔÇśgoodÔÇÖ reign no eclipses were recorded, not even a conspicuous comet.ÔÇŁ

15 However, when it comes to those eclipses that did not occur but that nevertheless appear in the historical record, rather than explaining these as being the result of intentional falsification of historical records for the purpose of political critique, Dubs imputes them to ÔÇťerrors of recording or transmission of the text [of the

Han shu]ÔÇŁ or of the records from which it was compiled.

16 DubÔÇÖs view was that Han records may have omitted eclipses, but eclipses were seldom falsely inserted into the record.

Like Eberhard and Dubs, Swedish-American scholar Hans Bielenstein (1920-2015) believed that the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ was a pattern of political opinion expressed through the recording and omitting of anomalous events. His well-known essay, ÔÇťAn Interpretation of the Portents in the TsÔÇÖien-Han-Shu,ÔÇŁ published in

Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in 1950 also analyzes the anomalies recorded in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ and

Ben ji as reflecting approbation or critique of the emperor. Bielenstein shared EberhardÔÇÖs and DubsÔÇÖ view that in the Western Han period, solar eclipses had the potential to be used as substance for the critique of political leadership. In BielensteinÔÇÖs view, this led to three practices: reporting actual eclipses as they happened in order to critique errant leaders, ÔÇťinventingÔÇŁ eclipses, and ÔÇťconcealingÔÇŁ actual eclipses in order to shield favored leaders from critique. According to his understanding, ÔÇť[c]oncealingÔÇŁ no eclipses ÔÇťwould certainly have indicated a very strong indirect criticism, while a recording of only some of them would have meant the contrary.ÔÇŁ

17 However, Bielenstein argued that inserting eclipses into historical records was severely punished, and so inventing eclipses happened only rarely; the omission of eclipses when no critique was necessary was a more frequent method of tailoring the record to oneÔÇÖs political opinion. His views on the

Han shu record of eclipses are thus similar to Dubs. Proceeding from the argument that there are few, if any, falsely inserted eclipses in the

Han shu, Bielenstein proposed a correlation between the pattern of recorded (or omitted) Western Han eclipses in the

Han shu and the pattern of all anomalies that were recorded in the

Han shu as having occurred in the Western Han; he asserted that this correlation represented the tendency toward approbation or disapproval toward each of the Han emperors among the class of scholar officials who controlled the making of the official records. In BielensteinÔÇÖs view, the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is thus an aggregate record of political opinion among this class over the course of the Western Han.

It can be seen therefore that there is a significant difference between DubsÔÇÖ and BielensteinÔÇÖs view, on the one hand, and EberhardÔÇÖs on the other, and that this difference has significant consequences for how the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is to be read. From EberhardÔÇÖs view, the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is rife with intentionally fabricated content. From the view of Dubs and Bielenstein, the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ may have omitted certain anomalies, but for the most part, those anomalies that did make it into the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ are accurate (or are at least all a faithful representation of history as it was recorded). (Dubs even went so far as to propose that the eclipses that were contained in the record but did not occur were just actual eclipses whose dates had been inaccurately recorded or transmitted.) EberhardÔÇÖs view wants to consign the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ to the rubbish bin of history; Dubs and BielensteinÔÇÖs view is more sympathetic.

These theories of interpreting the process by which the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ came to be point to the third problem in reading the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ which is that beyond the foreignness of its material-political philosophy and the uncertainty of its authorship (though this third problem relates to the problem of authorship), there has been uncertainty in terms of whether or not its contents were a compilation based on faithful, earnest historical records or are full of intentionally fabricated events that were part of an attempt to asperse political rulers with whom its Han historians disagreed. A skeptical view of the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ similar to EberhardÔÇÖs has persisted, and the status of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as an historical source has been left unsettled. A number of recent studies focus on the self-serving nature of anomaly interpretation in the Western Han as a weapon of factional infighting, suggesting a tendency to view the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as being a relic of partisan bickering.

18 The continued uncertainty in the status of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ has been a further obstacle to reading the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ and using it as a source of Han thought.

There is a way of analyzing the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that goes a long way in overcoming these obstacles. The main problem with the available theories of reading the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is that they do not integrate Ban GuÔÇÖs own account of how he compiled the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ in the preface to that chapter; nor do they utilize the contents in other chapters of the Han shu that are relevant to Ban GuÔÇÖs account of the compilation of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ Putting Ban GuÔÇÖs remarks together with certain clues in the formatting of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ reveals that is highly likely that the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ rather than being a copied text (as Eberhard and others have proposed), is in fact a composite text consisting of (at least) three different layers that were composed at three different points in time: two in the Western Han and one in the Eastern Han. Overall, far from being a tendentious presentation of history, it seems rather to reflect the attempt of the authors of its three different layers to merely demonstrate the connection between human action and natural anomaly through the presentation of historical examples. This paper attempts to demonstrate this by elucidating the discrete ÔÇťstratigraphic layersÔÇŁ of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ and applying quantitative reasoning to track and map them.

Stratigraphic Analysis of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ

Ban GuÔÇÖs Preface

In his preface to the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ Ban Gu describes an accretive process that formed the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ in which three different moments of authorship can be discerned

19:

1 Š╝óŔłł, Šë┐šžŽŠ╗ůňşŞń╣őňżî, ŠÖ»ŃÇüŠşŽń╣őńŞľ, ŔĹúń╗▓ŔłĺŠ▓╗ňůČšżŐŠśąšžő, ňžőŠÄĘÚÖ░ÚÖŻ, šé║ňäĺŔÇůň«Ś.

The Han arose, inheriting the aftertimes of the snuffing out of learning by the Qin. In the ages of [Thearch] Jing and [Thearch] Wu, Dong Zhongshu mastered the Springs and Autumns of Gongyang. He began promoting yin yang. He was the forebear of the Ruists.

2 ň«úŃÇüňůâń╣őňżî, ňŐëňÉĹŠ▓╗šęÇŠóüŠśąšžő, ŠĽŞňůŠŚĄšŽĆ, ňé│ń╗ąŠ┤¬š»ä, Ŕłçń╗▓ŔłĺÚî».

After [Thearch] Xuan and [Thearch] Yuan, Liu Xiang mastered the Springs and Autumns of Guliang, tabulated its calamities and fortunes, and transmitted it using the Hong fan. It [i.e., Liu XiangÔÇÖs scholarship on the Chunqiu] is different from [alt., interlocks with] Zhongshu.

3Ŕç│ňÉĹňşÉŠşćŠ▓╗ňĚŽŠ░Ćňé│, ňůŠśąšžőŠäĆňĚ▓ń╣ľščú. ŔĘÇń║öŔíîňé│, ňĆłÚáŚńŞŹňÉî.

By the time at which XiangÔÇÖs son Xin mastered Mister ZuoÔÇÖs Tradition, his understanding of the Springs and Autumns had already become distorted. Talk about the Five Elements Tradition was also exceedingly divergent.

4 Šś»ňĚ▓Ńęťń╗▓Ŕłĺ, ňłąňÉĹŃÇüŠşć, ňé│Ŕ╝ëšťşňşčŃÇüňĄĆńż»ňőŁŃÇüń║ČŠł┐ŃÇüŔ░ĚŠ░ŞŃÇüŠŁÄň░őń╣őňżĺŠëÇÚÖ│Ŕíî ń║ő, ŔĘľŠľ╝šÄőŔÄŻ, ŔłëňŹüń║îńŞľ, ń╗ąňé│Šśąšžő, ŔĹŚŠľ╝š»ç.

Therefore, I have embraced Zhongshu, made a distinction between Xiang and Xin, and transmitted and recorded the actions and affairs of Sui Meng, Xiahou Sheng, Jing Fang, Gu Yong, and Li Xun as they have been related by their disciples. Going up until Wang Mang, I proffer twelve generations, and thereby transmit the Springs and Autumns, compiling [all of this] into a chapter.

According to Ban Gu, the three moments at which the core contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ were compiled were: (1) the lifetime of early Western Han scholar Dong Zhongshu ŔĹúń╗▓Ŕłĺ (179-104 BCE), during the reigns of Han Thearch Jing Š╝óŠÖ»ňŞŁ (r. 157-141 BCE) and Thearch Wu Š╝󊺎ňŞŁ (r. 141-87 BCE); (2) the lifetime of late Western Han scholar Liu Xiang, at a point after the end of the reign of Han Thearch Yuan Š╝óňůâňŞŁ (48-33 BCE); and (3) Ban GuÔÇÖs own lifetime in the Eastern Han. (For the purpose of creating a stratigraphic model of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ I have omitted consideration of Liu XinÔÇÖs contribution. This is because compared to the contents derived from Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang, the content added by Liu Xin was relatively minor. However, an exhaustive mapping of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ must include the contents that can be attributed to Liu Xin.)

While the preface does not explicitly state that the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ reflects three different moments of authorship, when comparing this passage to the comments that are attached to the catalogue of anomalies listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ (as will be be done below), it becomes clear that Ban Gu was compiling the text primarily from two texts that resembled lists of comments: one was a list of comments that Dong Zhongshu had made about anomalous incidents described in the Gongyang zhuan ňůČšżŐňé│ (Gongyang Tradition) commentary to the Chunqiu; and the other was a similar list of comments that Liu Xiang had made about anomalous incidents described in the Guliang zhuan commentary. This is to say that both Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang were primarily interested in anomalies that were recorded as happening in the Spring and Autumn period.

Ban GuÔÇÖs preface also names the particular theoretical views used by Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang when they were making comments on Spring and Autumn anomalies. Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs was the material philosophy based on the concepts of yin ÚÖ░ and yang ÚÖŻ; Liu XiangÔÇÖs was the system outlined in the Hong fan (which included, as is evident from Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments cited in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ itÔÇÖs the Hong fanÔÇÖs Wuxing zhuan commentary). Ban Gu says that he then extended their analysis to the Western Han, expressed by him in the phrase shiÔÇÖer shi ňŹüń║îńŞľ ÔÇťtwelve generations,ÔÇŁ which makes up the third major moment of authorship.

Close reading of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ catalogue of anomalies and their comments reveals a text that closely resembles the process described by Ban Gu in his preface. The following section will present the structure of the comments to the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ catalogue of anomalies, with the goal of showing the consistency between Ban GuÔÇÖs description of the process by which the components of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ came into being and the structure of comments within the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ itself.

The Structure of Comments to the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ Catalogue of Anomalies

In the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ there are approximately 372 incidents of anomaly cited from historical sources. The sources from which these incidents of anomaly are culled are the Chunqiu (CQ), the Zuo zhuan (ZZ), the Guliang zhuan (GLZ), the Gongyang zhuan (GYZ), the Shu xu ŠŤŞň║Ć (Preface to the Documents, i.e. preface to the Shang shu: SS), a source referred to as Shi ji ňĆ▓ŔĘś (Records of the Scribe: SJ), which seems to be a generic term for a number of historical sources that originated in the late Warring States period, and sources of Qin and Western Han history (QHH) that Ban Gu does not name (but likely were imperial archival records available in the Eastern Han). A very small number of incidents listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ were recorded in the Chunqiu but appear to require some combination of the commentaries of the Zuo zhuan, the Guliang zhuan, or the Gongyang zhuan to render even a basic understanding of the account of anomaly that Ban Gu imputes to the Chunqiu.

The great majority (334, or 89.8%) of the anomalies listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ are cited from either the

Chunqiu or unnamed sources of Qin and Western Han history. The remainder (38, or 10.2%) are taken from those other sources listed above. The breakdown is as follows:

All but 1 of the 78 incidents for which Ban Gu quotes Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs remarks are brief passages from the

Chunqiu, the single exception (an account of a

zaišüŻ ÔÇťconflagrationÔÇŁ in the ancestral temple of Thearch Gao Úźś recorded as having occurred in 135 BCE, during the reign of Thearch Wu) being taken from the unnamed sources of Qin and Han history that Ban Gu used

20:

This is consistent with Ban GuÔÇÖs observation that Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs interest lay in the Chunqiu.

As another point of consistency between Ban GuÔÇÖs preface and the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ Ban Gu in the preface states that Dong Zhongshu was interested in the

Gongyang Chunqiu. Of the comments of Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments that Ban Gu appends to the anomalous events taken from the

Chunqiu, it is clear that Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs remarks were indeed directed at the account of history given in the

Gongyang commentary to the

Chunqiu. This can be seen, for example, in Ban GuÔÇÖs citation of Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs commentary on an event that is recorded in the

Chunqiu of the

Gongyang tradition as

da yu bao ňĄžÚŤĘÚŤ╣ ÔÇťa great shower of hailÔÇŁ and is dated there as having happened in the winter of the tenth year (650 BCE) of the reign of Lord Xi ňâľňůČ of Lu ´Ą╣ (r. 659-627 BCE).

21 A similar event is described in the

Chunqiu of the

Zuo zhuan and Guliang traditions as

da yu xueňĄžÚŤĘÚŤ¬ ÔÇťa great shower of snow.ÔÇŁ

22 These two different descriptions presumably refer to the same event.

Ban Gu cites Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments on the hail shower recorded in the GongyangÔÇÖs version of the Chunqiu:

ŔĹúń╗▓Ŕłĺń╗ąšł▓ňůČŔäůŠľ╝ÚŻŐŠíôňůČ. šźőňŽżšé║ňĄźń║║ńŞŹŠĽóÚÇ▓šżĄňŽż. ŠĽůň░łňú╣ń╣őŔ▒íŔŽőŔźŞÚŤ╣. šÜćšé║ŠťëŠëÇŠ╝ŞŔäůń╣č. Ŕíîň░łňú╣ń╣őŠö┐ń║Ĺ.

23

Dong Zhongshu held that the Lord was coerced by Lord Huan of Qi. He installed a concubine as his wife and did not dare to enter [his] harem of concubines. Therefore, the image of preferential treatment of one [individual] appeared in the form of hail. In all cases, this means that there has been saturation by coercion. That is to say that governing marked by preferential treatment of one [individual] was being carried out.

Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs observation that Lord Xi of Lu had installed a concubine as his wife is a reference to the

Gongyang commentary to the

Chunqiu record two years before, in the eighth year (652 BCE) of Lord XiÔÇÖs reign. The

Chunqiu records that Lord Xi had that year ÔÇťperformed large-scale sacrifices in the great ancestral temple, and used [the occasion] to present [his] wifeÔÇŁ ŔĄůń║ÄňĄžň╗č. šöĘŔç┤ňĄźń║║.

24 The

Gongyang commentary proposes that the language of the

ChunqiuÔÇÖs record of this event indicates the impropriety of Lord XiÔÇÖs using the occasion of the

ti ŔĄů ÔÇťlarge-scale sacrificesÔÇŁ to announce his wife, Sheng Jiang Ŕü▓ňžť,

25 to the ancestral spirits: ÔÇťWhat does

yongšöĘ ÔÇśuseÔÇÖ mean?

yong means that it [i.e., the occasion] should not have been used [in this way]. What does

zhi Ŕç┤ ÔÇśpresentÔÇÖ mean?

zhi means that [a wife] should not have been presented [in this way]. Using the large-scale sacrifices to present oneÔÇÖs wife is not ritually properÔÇŁ šöĘŔÇůńŻĽšöĘŔÇůńŞŹň«ťšöĘń╣čŔç┤ŔÇůńŻĽŔç┤ŔÇůńŞŹň«ťŔç┤ń╣čŔĄůšöĘŔç┤ňĄźń║║ڣךŽ«ń╣č.

26

In addition to signaling ritual impropriety, according to the

Gongyang commentary for this passage of the

Chunqiu, it was an intentional omission that the language of the

Chunqiu record here does not refer to Sheng Jiang by the conventional construction that would be used for her as the wife of a duke, Jiang shi ňžťŠ░Ć ÔÇťthe one of the surname JiangÔÇŁÔÇöwhich would have referred to her by her surname, Jiangňžť.

27 According to the

Gongyang commentary, this omission shows that the compiler of the

Chunqiu (Kongzi was presumably understood as the compiler of the

Chunqiu by the Gongyang author) did not believe that Sheng Jiang should be given the full status and treatment that otherwise redounded to the wife of the Lu monarch. The Gongyang position is that by this omission, the

Chunqiu compiler in fact derided Lord Xi for installing a mere concubine as his wife: ÔÇťIt rebukes [him] for taking a concubine as [his] wifeÔÇŁ ŔşĆń╗ąňŽżšé║ňŽ╗.

28 The

Gongyang zhuan surmises that Lord Xi been coerced into installing Sheng Jiang as his wife: ÔÇťMost likely [he] had been coerced by [the circumstance that] the Qi maid[s] accompanying the bride arrived firstÔÇŁ ŔôőŔäůń║ÄÚŻŐň¬Áňą│ń╣őňůłŔç│ŔÇůń╣č.

29 The insinuation here appears to be that the monarch of Qi at the time, Lord Huan Šíô (d. 643 BCE), had for political reasons wanted Sheng Jiang, a woman of Qi, to become Lord XiÔÇÖs wife, and had forced Lord Xi to install Sheng Jiang as his wife by having her arrive first to Lu (as one of the bridal maids) before Lord Xi could initiate wedding rituals with the woman he intended to be his bride.

30

According to Dong Zhongshu, the large amount of hail recorded two years after Lord XiÔÇÖs presentation of Jiang Sheng at the large-scale sacrifices was the xiang Ŕ▒í ÔÇťimageÔÇŁ of the improperly preferential treatment Lord Xi gave to his wife, Sheng Jiang, whom he had been forced to marry by coercion. By Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs account, Lord Xi was partial to Sheng Jiang to the point that he did not install concubines in his harem. The hail was thus a manifestation of the imbalance that had been introduced into the Lu court by the harmful influence of the Qi monarch.

It is clear that Dong Zhongshu was working with the

Gongyang Chunqiu version of history in his analysis of this episode. Neither the

Chunqiu version of the

Guliang zhuan nor that of the

Zuo zhuan mention hail. (As mentioned above, both describe the unusual weather in Lu in the winter of that year, the tenth year of Lord XiÔÇÖs reign, as

da yu xueňĄžÚŤĘÚŤ¬ ÔÇťa great shower of snow.ÔÇŁ) Moreover, the language of Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs explanation of the cause of the hail follows the diction of the GongyangÔÇÖs interpretation of the

Chunqiu language relating Lord XiÔÇÖs presentation of his wife in the ancestral temple. For example, the phrase

gong xie yu Qi Huan gong ňůČŔäůŠľ╝ÚŻŐŠíôňůČ in Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs explanation mirrors the phrase

gai xie yu Qi yingn├╝ zhi xian zhi zhe ye ŔôőŔäůń║ÄÚŻŐň¬Áňą│ń╣őňůłŔç│ŔÇůń╣č of the

Gongyang commentary. In contrast, there is nothing about coercion on the part of Qi in either the

Zuo zhuan or the Guliang commentaries regarding the

Chunqiu record of the rites Lord Xi carried out in the ancestral temple in the eighth year of his reign.

31 In fact, according to the

Zuo zhuan account of the large-scale sacrificesŔĄů performed that year by Lord Xi, the fu ren ňĄźń║║ referred to in the

Chunqiu record was in fact not Sheng Jiang, but Ai Jiang ňôÇňžť, the dead wife of Lord XiÔÇÖs father, Lord Zhuang ŔÄŐ (r. 694-662 BCE).

32 The version of the

Chunqiu that Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comment in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is referring to is undoubtedly that of the Gongyang tradition.

All other comments by Dong Zhongshu that are appended to events that are recorded in the Chunqiu similarly can be found to be directed at the version of that text that appears in the Gongyang version. Likewise, in another point of consistency with the Ban GuÔÇÖs preface, none of the concepts from the systematic taxonomy of anomalies presented in the Hong fan ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ (yao ňŽľ ÔÇťeerie occurrences,ÔÇŁ nie ňşŻ ÔÇťabnormalities,ÔÇŁ huo ŠŚĄ ÔÇťstartling maladies,ÔÇŁ ke šŚż ÔÇťinfections,ÔÇŁ sheng šťÜ ÔÇťaberrant generations,ÔÇŁ and xiang šąą ÔÇťsalient deviationsÔÇŁ) appears in Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments about Chunqiu history. Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments as they appear in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ thus match with Ban GuÔÇÖs description. All appearances suggest that Dong Zhongshu had produced some kind of annotated catalogue of the anomalies that appeared in the Chunqiu Gongyang zhuan, that this catalogue had come down to Ban Gu (more on this below), and then Ban Gu used that text as foundational material to compile the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ

Contents by Liu Xiang (ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ Layer 2)

Like Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments, Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments appended to anomalous events catalogued in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ also demonstrate consistency with the observations that Ban Gu makes in his preface. Of the 372 incidents of anomaly catalogued in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ for 146 (or 39.2%) of these, Ban Gu cites Liu XiangÔÇÖs remarks about each of these incidents as they are described in the historical source from which Ban Gu cites them:

As can be seen in the above chart, Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ reflect a predominant interest in anomalies that occurred in the Chunqiu period, with 109 (or 74.7%) of Liu XiangÔÇÖs 146 comments corresponding to events that happened in or prior to Chunqiu times. This is consistent with Ban GuÔÇÖs comment in the preface that Liu Xiang was interested in cataloguing anomalies from the Chunqiu period (and with a particular interest in the commentary of the Chunqiu Guliang zhuan). (Since Liu Xiang also comments on incidents that occurredÔÇöor were recorded as occurringÔÇöin the late Warring States and Western Han period, to describe his comments, I have used the category of ÔÇťperiod of occurrenceÔÇŁ (referring to the historical events on which Liu Xiang commented) to classify his comments, dividing them into either the period recorded in the Chunqiu or the period between ca. 350 BCE and 8 C.E.)

Also as described in the preface to the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments integrate the theoretical view of the Hong fan Wuxing zhuan, which contains (as described above) a detailed taxonomy to support the theory that anomalies arise because of disturbances to the material ecosphere caused by human corruption and errant political rule. Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments apply the Wuxing zhuan taxonomy to the historical record. An example of this is Liu XiangÔÇÖs remarks about a series of events recorded in the Zuo zhuan. In the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ catalogue, Ban Gu summarizes the Zuo zhuan account and then appends Liu XiangÔÇÖs comment:

ňĚŽŠ░Ćňé│Úş»ŔąäňůČŠÖé. ň«őŠťëšöčňą│ňşÉŔÁĄŔÇŤ. Šúäń╣őÚÜäńŞő. ň«őň╣│ňůČŠ»Źňů▒ňžČń╣őňżíŔÇůŔŽőŔÇîňĆŚń╣ő. ňŤáňÉŹŠŤ░Šúä. ÚĽĚŔÇîšżÄňąŻ. š┤Źń╣őň╣│ňůČ. šöčňşÉŠŤ░ńŻÉ. ňÉÄň«őŔçúń╝ŐŠłżŔ«ĺňĄ¬ňşÉšŚĄŔÇ║ń╣őÔÇŽňŐëňÉĹń╗ąšł▓ŠÖéňëçšüźšüŻŔÁĄšťÜń╣őŠśÄŠçëń╣č.

33

According to Mister ZuoÔÇÖs Tradition, in the time of Lord Xiang of Lu, there was born in the state of Song ň«ő a female child who was ruddy and hairy. She was abandoned beneath an embankment. A servant of Gong Ji, the mother of Lord Ping of Song, saw her and brought her in. Accordingly, her name was Qi. She grew and was beautiful and pleasing. She was installed in the household of Lord Ping. She gave birth to a child named Zuo. Thereafter, Song vassal Yi Li slandered the grand heir Cuo and murdered himÔÇŽLiu Xiang held that this was [a case of the principle that] at times there will thus be manifestly evident responses in the form of fire disasters and red aberrant generations.

Ban Gu here is summarizing an account given in the

Zuo zhuan commentary to

Chunqiu content for the 26th year (547 BCE) of the reign of Lord Xiang Ŕąä of Lu (r. 572-542 BCE). While the

Chunqiu records only that ÔÇťin the autumn, the Lord of Song put to death his heir apparent, CuoÔÇŁ šžőň«őňůČŠ«║ňůÂńŞľňşÉšŚĄ

34, the

Zuo zhuan commentary for this year provides a detailed account of events leading up to the execution of Cuo šŚĄ.

35

As Ban GuÔÇÖs summary of the Zuo zhuan account tells, the Zuo zhuan begins its explanation of CuoÔÇÖs death by describing details about the birth of CuoÔÇÖs younger half-brother, Zuo ńŻÉ, and about the unusual physical features of ZuoÔÇÖs mother, Qi Šúä, at birth and her childhood experience. The Zuo zhuan account explains that Qi was the biological daughter of Situ Rui ňĆŞňżĺŔŐ«, a dafu ňĄžňĄź ÔÇťgrand counselorÔÇŁ in the Song court, and that she had a strange physical appearance (apparently starting from when she was born), being chi er mao ŔÁĄŔÇŤ ÔÇťruddy and hairy.ÔÇŁ According to the Zuo zhuan account, Qi was abandoned as a young child under an embankment; she was discovered by a servant of Gong Ji ňů▒ňžČÔÇöthe wife of Lord Gong ňů▒ňůČ of Song (r. 588-576 BCE)ÔÇöand was raised in Gong JiÔÇÖs household. Qi grew into a beautiful woman, and Lord GongÔÇÖs successor, Lord Ping ň╣│ňůČ, was struck by her beauty and took her as his concubine. Qi bore a son, Zuo.

Song court. The Song vassal Yi Li ń╝ŐŠłż (d. 547 BCE), ÔÇťserves as the HeirÔÇÖs Court PreceptorÔÇŁ šé║ňĄžňşÉňćůňŞź but ÔÇťdoes not enjoy any favorÔÇŁ šäíň»Á, and therefore resents Cuo. Another Song courtier, He ňÉł, who serves at court as zuoshi ňĚŽňŞź ÔÇťthe Preceptor of the Left,ÔÇŁ also fears and resents the ducal heir for his severe demeanor. Yi Li fabricates evidence to support a false charge that Cuo is conspiring to overthrow Lord Ping. Lord Ping is taken in by Yi LiÔÇÖs ploy and imprisons hiss son. Cuo sends for his brother Zuo to exonerate him, but He Zuoshi intentionally delays Zuo. Cuo despairs and hangs himself. Lord Ping gradually realizes that he has been deceived and has Yi Li boiled alive.

Liu XiangÔÇÖs remarks on the

Zuo zhuan account, featuring the terms

ming ying ŠśÄŠçë ÔÇťmanifestly evident responsesÔÇŁ and

chi sheng ŔÁĄšťÜ ÔÇťred aberrant generationsÔÇŁ understands this series of events through the lens of the

Wuxing zhuan, which observes that ÔÇťat times there will thus be red aberrant generationsÔÇŁ ŠÖéňë犝ëŔÁĄšťÜ when the

shiŔŽľ ÔÇťseeingÔÇŁ of the head of state is

bu ming ńŞŹŠśÄ ÔÇťnot clear.ÔÇŁ

36 To construct Liu XiangÔÇÖs view based on the conceptual framework of the

Wuxing zhuan, Liu XiangÔÇÖs understanding is that Lord PingÔÇÖs clouded perception that leads him to view the actions of his son through the false aspersions of a scheming vassal was already exerting an influence at the time of QiÔÇÖs birth. Her ÔÇťruddy and hairyÔÇŁ physical features had been generated from the young Lord PingÔÇÖs faltering powers of perception.

While the

Zuo zhuan provides an extensive description of the circumstances surrounding the execution/suicide of Cuo, neither the

Gongyang zhuan nor the

Guliang zhuan provide any commentary to the

Chunqiu record of CuoÔÇÖs death.

37 It is unique to the

Zuo zhuan. In the preface to the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ Ban Gu stresses Liu XiangÔÇÖs interest in the

Guliang zhuan, observing that Liu Xiang

zhi Š▓╗ ÔÇťmasteredÔÇŁ it, but clearly Liu Xiang was reading the

Zuo zhuan as well and used it as a source for understanding the

Chunqiu.

Liu XiangÔÇÖs use of

Wuxing zhuan terms and logic in his remarks connecting QiÔÇÖs rubicund complexion to the death of Cuo is a pattern that runs through comments attributed to Liu Xiang in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ For the 146 anomalous incidents from historical records to which the comments of Liu Xiang are attached, Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments to 32 (or 21.9%) of these feature the distinct terminology of the

Wuxing zhuan. They are as follows:

Liu XiangÔÇÖs use of the Wuxing zhuan as a material theory to classify and delineate the cause of anomalies listed in the historical record is consistent with Ban GuÔÇÖs observation in his preface to the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that Liu Xiang made use of the Hong fan (a phrase that in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ refers to both the Hong fan and its commentary, the Wuxing zhuan) to explicate and transmit the history outlined in the Chunqiu. As Liu Xiang was reviewing the historical record, he was looking at it from a perspective heavily influenced by the political-material philosophy embodied in the Wuxing zhuan.

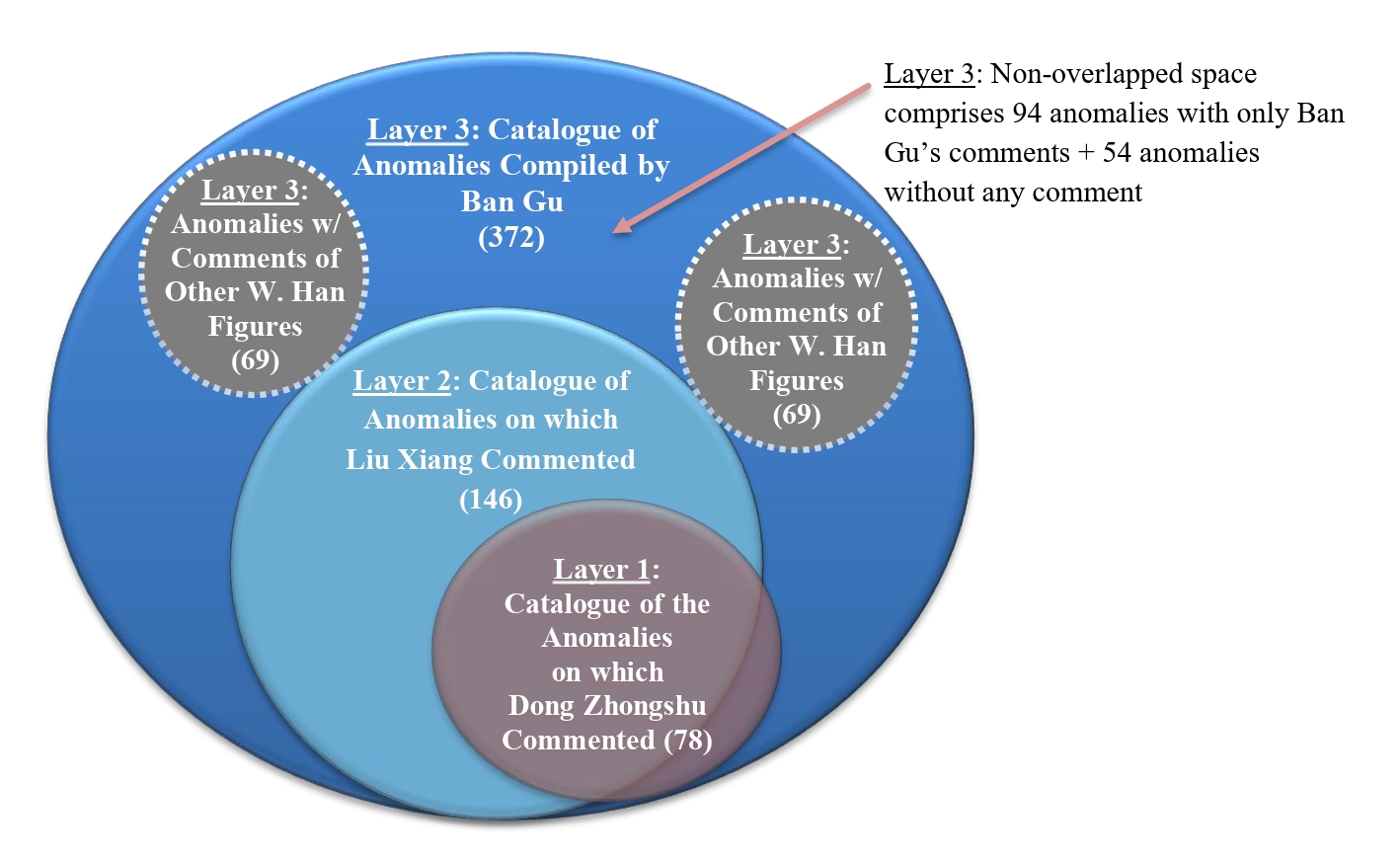

There is considerable overlap in the incidents to which the comments of Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang are attached. Of the 78 incidents to which Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments are appended, Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments are given for 69 of them, and all 69 of these accounts are taken from the Chunqiu. This suggests that Liu Xiang was basing his own catalogue of historical anomalies (with his comments attached) on some work that contained a record of Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments on anomalous incidents in the Chunqiu.

Contents by Ban Gu: Anomalies Without Comment or With Anonymous Comments (ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ Layer 3)

In addition to the accounts of anomaly to which the comments of Liu Xiang and Dong Zhongshu are attached (either together or separately), there are some 148 incidents of anomaly (or 39.8% of all the anomalies listed) that either do not contain comments or contain comments that are not attributed to Dong Zhongshu, Liu Xiang, or any other figure indicated by name. Among these, 54 accounts that do not have any specific comments attached to them; the other 94 are accompanied by comments for which no ascription is indicated, as if it were the voice of Ban Gu himself commenting on the account directly. These are tabulated in

Table 5 according to the source texts of the accounts listed in these entries. The following sections will argue that Ban Gu added this content to the catalogues of Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang, thus forming the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ

An example of an incident of anomaly listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that does not contain any comments is an account of an extraordinary sequence of events having to do with the birth of a baby recorded as having occurred in 3 BCE:

ňôÇňŞŁň╗║ň╣│ňŤŤň╣┤ňŤŤŠťł, ň▒▒ÚÖŻŠľ╣Ŕłçňą│ňşÉšö░šäíňŚçšöčňşÉ. ňůłŠť¬šöčń║ł, ňůĺňŚüŔů╣ńŞş, ňĆŐšöč, ńŞŹŔłë, ŔĹČń╣őÚÖîńŞŐ. ńŞëŠŚą, ń║║ÚüÄŔü×ňŚüŔü▓, Š»ŹŠÄśŠöÂÚĄŐ.

38

In the fourth month of the fourth year [3 BCE] of the Jianping ň╗║ň╣│era [6-3 BCE] of Thearch AiÔÇÖs reign [r. 7-1 BCE], Tian Wuse, a young woman of Fangyu [County] in Shanyang [Commandery], gave birth to a child. Two months before she gave birth, the baby had cried out from within her belly. And then, when it was born, the baby did not stir to life. It was buried on a small road among the fields. Three days later, a person passed by and heard the sound of something crying out. The mother dug the baby up, took it in, and raised it.

This account of a stillborn child that awakened to life days after having been buried is listed under the section of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that describes the consequences of a rulerÔÇÖs having failed to achieve

huang ji šÜ犹Á ÔÇťroyal/august perfectionÔÇŁÔÇöa concept taken from the

Hong fan Wuxing zhuan. An apparently dead newborn buried in the earth coming to life again in its basic logical structure (a child placed below the ground being lifted up again to the world of the living) follows the structure of ÔÇťinfections in which humans who are below attack those who are aboveÔÇŁ ŠťëńŞőń║║ń╝ÉńŞŐń╣őšŚż occurring when the value of royal/august perfection is not achieved by the head of the state.

39

However, in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ there are no statements explicitly interpreting the event. Its significance is to be inferred from its place in the structure of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ Also, there is no information indicating that the miraculous revival of the stillborn child was an event that was viewed as having any omenological significance at the time it is reported to have happened. It appears to have come into the historical record as a report of a wondrous event that was circulating in Shanyang ň▒▒ÚÖŻ Commandery in 3 BCE. It is simply an account of an anomalous incident without comment, to be interpreted based on its location in rubric of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ.

Example of an Anonymous Comment

An example of an event in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that has a comment (but without attribution) is an account of the absence of ice formation in the winter of 117 BCE:

ŠşŽňŞŁňůâšőęňůşň╣┤ňćČ, ń║íňć░. ňůłŠś», Š»öň╣┤ÚüúňĄžň░çŔ╗ŹŔíŤÚŁĺŃÇüÚťŹňÄ╗šŚůŠö╗šąüÚÇú, šÁĽňĄžň╣Ľ, š¬«Ŕ┐Żňľ«ń║Ä, ŠľČÚŽľňŹüÚĄśŔÉČš┤Ü, Úéä, ňĄžŔíîŠůÂŔ│×. ń╣âÚľöŠÁĚňćůňőĄňő×, Šś»ňÁŚÚüúňŹÜňúźŔĄÜňĄžšşëňůşń║║Šîüš»ÇňĚíŔíîňĄęńŞő, ňşśŔ│ťÚ░ąň»í, ňüçŔłçń╣ĆňŤ░, ŔłëÚü║ÚÇŞšŹĘŔíîňÉŤňşÉŔęúŔíîňťĘŠëÇ. ÚâíňťőŠťëń╗ąšł▓ńż┐ň«ťŔÇů, ńŞŐńŞ×šŤŞŃÇüňżíňĆ▓ń╗ąŔü×. ňĄęńŞőňĺŞňľť.

40

In the winter of the sixth year [117 BCE] of the Yuanshou era [122-117 BCE] of the reign of Thearch Wu, there was no ice. Prior to this, the Great Generals Wei Qing and Huo Qubing year after year had been dispatched to attack [the] Qilian [Mountains]. They reached the ends of the Great Deserts, relentlessly pursued Chanyu, and cut off 100,000 heads, plus some tens of thousands more. When they returned, celebrations and commendations were conferred in great profusion. At the same time, out of concern that the realms within the seas had become exhausted with laborious toiling, that year the academician Chu Da and others (six people in all) were dispatched to carry the [ThearchÔÇÖs] credentials and make a circuit around the realms under heaven. They granted succoring relief to widowers and widows, provided aid and gave to the indigent and the impoverished, and lifted up those places to which noble masters of distinguished comportment, having been abandoned and scattered, had come. In the commanderies and kingdoms, there were those who took these as constructive and appropriate acts and sent reports up to the Chief Minister and Chief Prosecutor to inform them about it. There was universal rejoicing in the realms under heaven.

The description of the anomalous event itself (an absence of the formation of ice in the winter of 117 BCE) is accompanied by a long, unattributed comment that describes the surrounding historical circumstances. For several years prior to that winter, Thearch Wu had sent two of his most capable generals, Wei Qing ŔíŤÚŁĺ (d. 106 BCE) and Huo Qubing ÚťŹňÄ╗šŚů (140-117 BCE) to conduct raids against the Xiongnu ňîłňą┤ in the frontiers of the empire around the Qilian šąüÚÇú mountain range and beyond. According to the comment, during these raids, Wei Qing and Huo Qubing pursued the supreme Xiongnu leader (referred to in this passage by his surname Chanyu ňľ«ń║Ä) and brutally executed more than 100,000 Xiongnu individuals. When they returned to ChangÔÇÖan, they were celebrated and honored as heroes. The comment juxtaposes the brutality carried out against the Xiongnu by Thearch WuÔÇÖs lauded generals with the generous treatment that the emperorÔÇÖs relief mission, led by the scholar Chu Da ŔĄÜňĄž and five other deputies, afford to needy and disaffected subjects of the empire who resided in the territorial spaces that were the object of its control (i.e., hai nei ŠÁĚňćů ÔÇťthe realms within the seasÔÇŁ and tian xia ňĄęńŞő ÔÇťthe realms under heavenÔÇŁ).

This entryÔÇÖs placement in the structure of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ insinuates that the cause of the absence of ice was the radical difference in attitudes towards humanistic values among the deputies of Thearch WuÔÇÖs regime and off-kilter patterns in the rewarding of high-ranking state officers. Wei Qing and Huo QubingÔÇÖs brutal campaign was celebrated in the Han capital, but Chu DaÔÇÖs highly beneficial tour of the empire received only a modest commendation originating from local officials. This entry in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is listed under the section of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ that describes anomalies that occur when there is the condition of shi

zhi buming ŔŽľń╣őńŞŹŠśÄ ÔÇťseeing not being clearÔÇŁ, which includes heng ao Šüćňąž ÔÇťconstant heatÔÇŁÔÇöagain, an analytical category taken from the

Hong fan Wuxing zhuan.

41 In the unattributed comment in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ explicating the corresponding

Wuxing zhuan passage, the issues that grow out of ÔÇťseeing not being clearÔÇŁ are ÔÇťnot being able to perceive what is benevolent and what is maliciousÔÇŁ ńŞŹščąňľäŠâí, which leads to a practical consequence of ÔÇťthose who are without merit receive commendations, those who transgress are not executed, and the hundred officers fall into abandonment and recklessnessÔÇŁ ń║íňŐčŔÇůňĆŚŔ│׊ťëšŻ¬ŔÇůńŞŹŠ«║šÖżň«śň╗óń║é.

42 Huo Qubing in particular is an embodiment of this formulation, especially considering the critical attitude (expressed elsewhere in the

Han shu) towards Huo QubingÔÇÖs neglect and mistreatment of the soldiers under his command combined with the brutality of his actions in warfare described here in the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ

43

The unattributed commentary to this passage of the

Wuxing zhuan given in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ includes an analysis at the material level in which the physical effect of failure in seeing is disruption of

huo qišüźŠ░ú ÔÇťfire vaporsÔÇŁ: ÔÇťall injuries done to seeing bring illness to fire vaporsÔÇŁ ňçíŔŽľňéĚŔÇůšŚůšüźŠ░ú.

44 This effect causes cycles of heat to become unbalanced, resulting in harm to human society: ÔÇťheat consequently warms in the winter, spring and summer become disharmonious, and this injures and brings illness to the commonfolkÔÇŁ ňąžňëçňćČŠ║źŠśąňĄĆńŞŹňĺîňéĚšŚůŠ░Ĺń║║.

45 The analytical voice points out that failures in seeing are brought about by a lack of diligence in applying oneself to the accurate and discriminating perception of reality, and warmth is the material embodiment of laxness: ÔÇťthe remissness is in indolence and dilatoriness, and so its unfavorable state is indolenceÔÇŁ ňĄ▒ňťĘŔłĺšĚꊼůňůÂňĺÄŔłĺń╣č.

46 It is thus apparent that the gist of the comments about the absence of ice in this entry points to a failure in Thearch WuÔÇÖs powers of perception in his appointment and commendation of state officers.

This entry is thus a brief commentary describing the absence of ice in the winter of 117 BCE followed by a long unattributed comment that gives an account of historical events happening around the same time. Both Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang in theory could have been the author of the comment, but there is no indication of that. Rather, the critical view toward Thearch Wu suggested in the comment is completely consistent with Ban GuÔÇÖs views in the ÔÇťWei Qing Huo Qubing zhuanÔÇŁ ŔíŤÚŁĺÚťŹňÄ╗šŚůňé│ chapter containing Ban GuÔÇÖs account of Huo QubingÔÇÖs biography. (Even the language of the accounts is similar, with the nameless commentator praising Chu DaÔÇÖs ability to bring

xi ňľť ÔÇťrejoicingÔÇŁ to the realms under heaven using the same language as Ban GuÔÇÖs laudatory remarks about the ability of Huo QubingÔÇÖs peer and foil, Wei Qing, to

xi shiňľťňúź ÔÇťbring joy to the soldiers.ÔÇŁ

47)

The question thus arises as to who added the uncommented accounts and the accounts with unattributed comments into the catalogue. And, moreover, who authored the unattributed comments?

For many of these 148 accounts for which there are no comments appended or the appended comments are not attributed to anyone, it is not possible to positively ascertain if they had previously come to the attention of either Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang (or any other figure in the Western Han tradition of anomaly-centered political philosophy) and had been compiled into a catalogue analyzing the connection between anomalous event and human corruption. From all appearances, Ban Gu took these from general historical records that functioned to record the events themselves without comments or interpretation. Where Dong Zhongshu is concerned, a certain proportion of these (about half) would have occurred after his death, and the same would have been true of a smaller proportion (those that were recorded as happening after 6 BCE) in the case of Liu Xiang, so that it is impossible that a certain set of the 148 had previously come to the attention of either one or both of them. For those events that were recorded as having occurred before the respective deaths Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang, Ban GuÔÇÖs interest in the history of the tradition of anomaly-centered political philosophy would likely have prompted him to include their remarks (or those of any other figure) if there had been a record that they had made any comments about those events. Judging from his remarks in the preface to the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ Ban Gu was wary of the views of certain sources (such as Liu Xin and the figures of Liu XinÔÇÖs generation and thereafter) on anomalies in the historic record, so that Ban Gu likely would have indicated the origin of views and comments that he included in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ but that did not originate from him directly.

For those incidents in which there are only unattributed comments attached to accounts of anomalies, the absence of attribution suggests that Ban Gu himself in compiling ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ had appended his own comments to these anomalous events that had previously not been commented on (as far as the records that Ban Gu was using showed) or else had been commented on in a way he viewed as inaccurate, and that in such cases he removed any previous comments before attaching his own. It is also possible that certain events included in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ may have been listed in works compiled by Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang but were simply not commented on in those works. However, there is no way to demonstrate that anomalies that do not have a comment by Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ ever were compiled by them into a catalogue.

Quantitative analysis of this set of incidents (uncommented and un-attributively commented accounts) compared to those to which the comments of Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang are attached leads one to believe that these sets of accounts arose from different principles of selection. Dong Zhongshu, judging from the incidents to which his comments were attached, was almost purely (98.7%) focused on anomalies in

Chunqiu history. Liu Xiang, in turn, had a majority focus (74.7%) on

Chunqiu-era history with a much smaller secondary interest (25.3%) in anomalies in Qin and Western Han history. This is consistent with Ban GuÔÇÖs remark in the preface that Liu XiangÔÇÖs scholarship on anomalies in history was focused on

Chunqiu history.

48 In contrast, the majority (121 accounts of 148, or 81.8%) of the set of uncommented and un-attributively commented accounts are devoted to anomalies in Qin and Western Han history, while reflecting only a minor secondary interest (27 of 148, or 18.2%) in

Chunqiu-era history. Given that Ban Gu states in his preface that his contribution to this cataloguing of anomalies in history was to add content from the Western Han (in Ban GuÔÇÖs language, ÔÇťproffer the twelve generationsÔÇŁ) up until the time of Wang Mang šÄőŔÄŻ (9-23 CE), the most likely possibility for the person who added the uncommented accounts from the Western Han and the accounts that have only unattributed comments (and their comments) is Ban Gu.

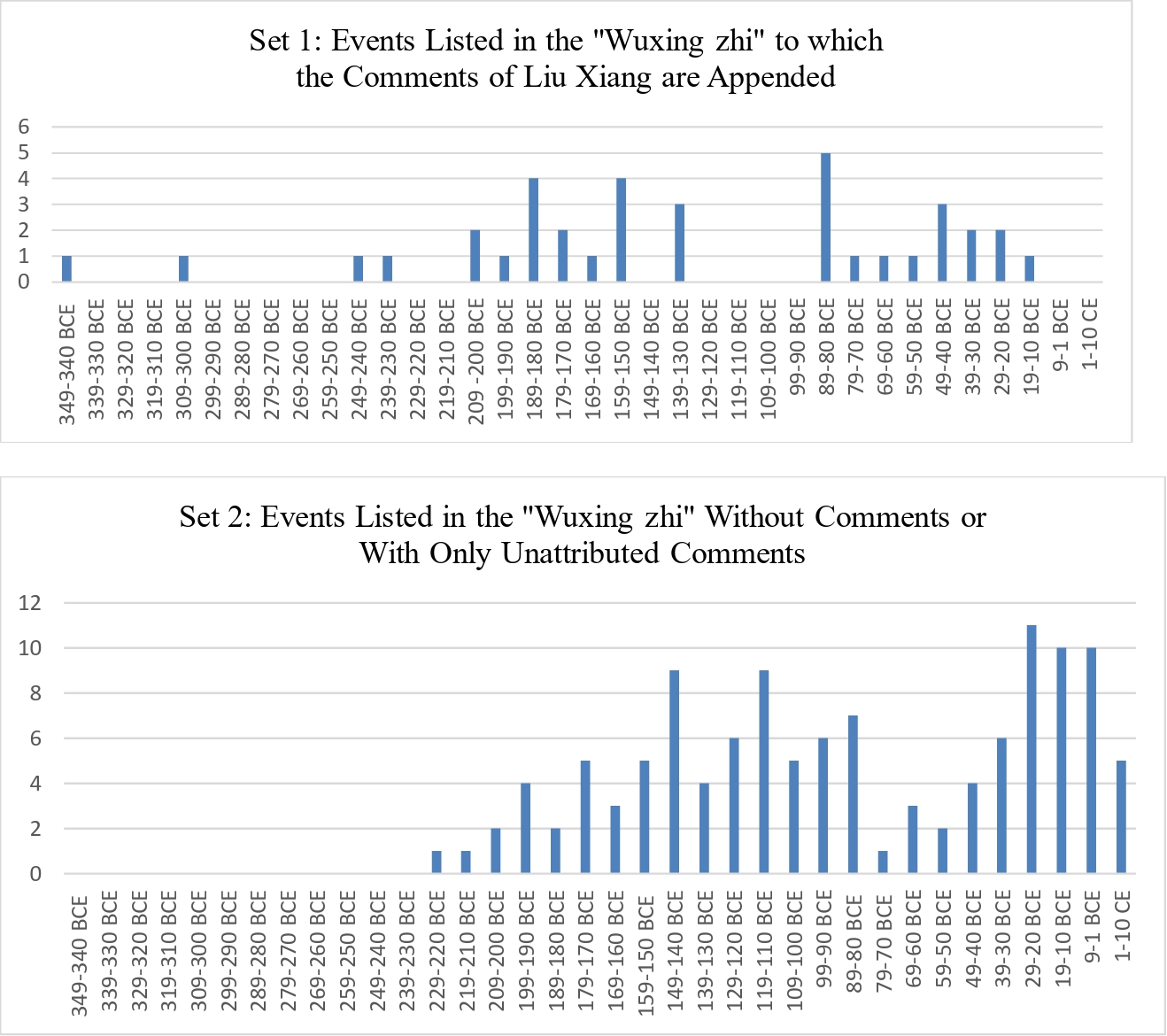

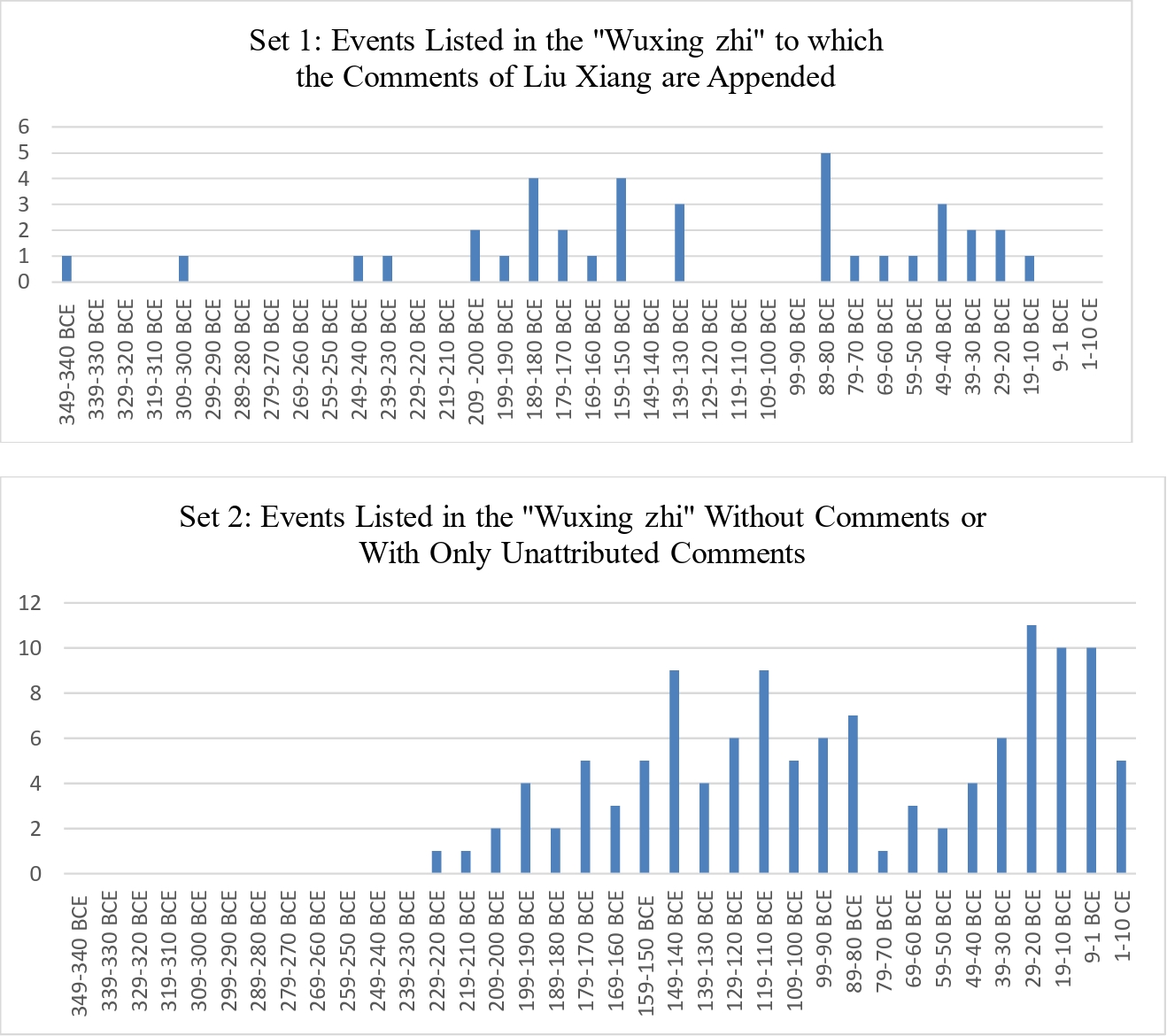

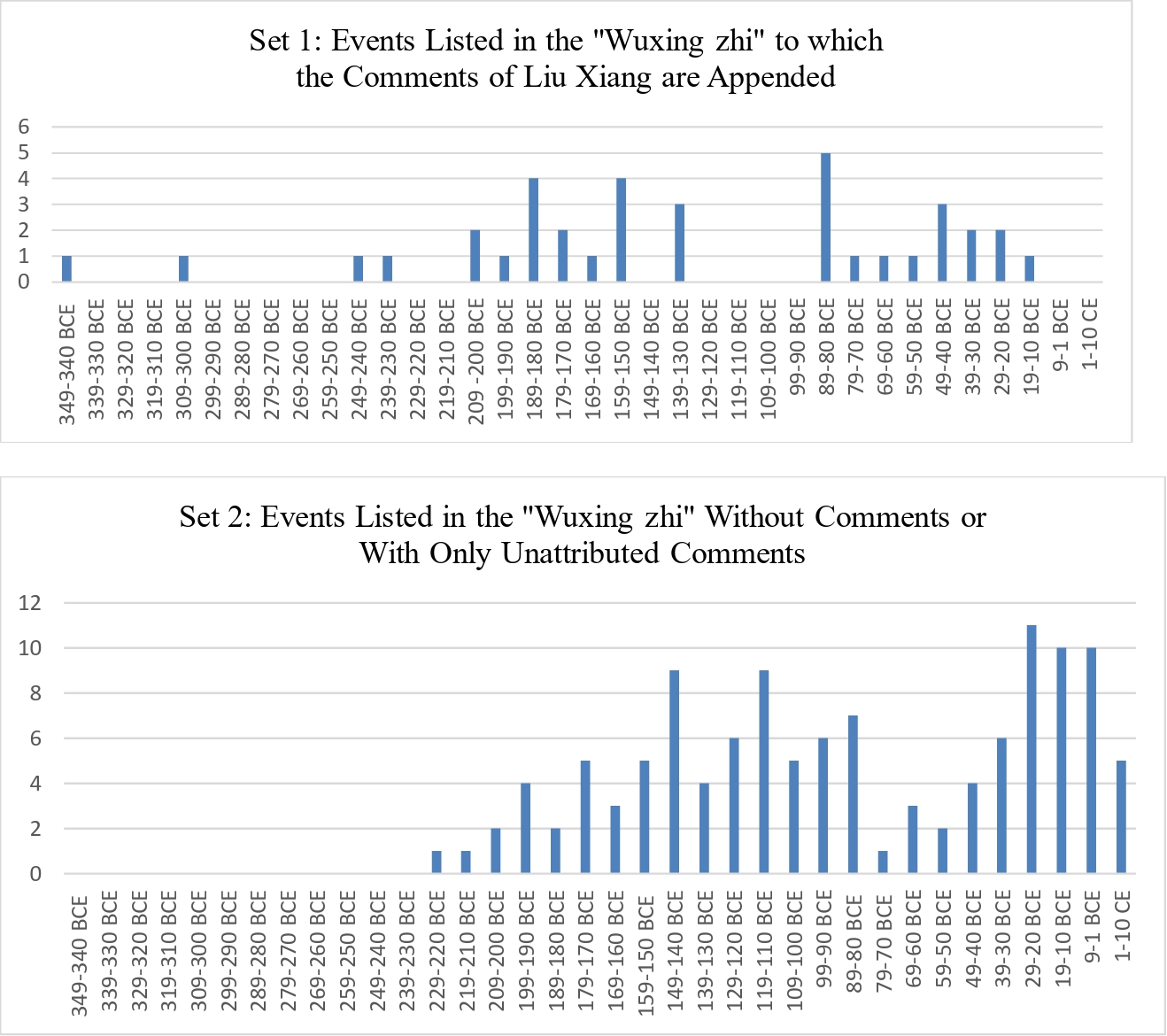

Comparing the time distribution of accounts Qin and Western Han anomalies to which the comments of Liu Xiang are appended (Set 1) with those accounts of Qin and Western Han anomalies that consist of uncommented or un-attributively commented accounts (Set 2) reveals obvious differences between the group of historical anomalies to which the comments of Liu Xiang are attached and the group of uncommented and un-attributively commented accounts:

As can be seen from the above charts, events from Set 1 are clustered around two periods: a period (from 209-130 BCE) between the establishment of the Han dynasty up until the beginning of the reign of Thearch Wu (141-87 BCE), and a period (84-10 BCE) that roughly corresponds to the lifetime of Liu Xiang himself (79-6 BCE). (The latest of the events on which Lu Xiang appears to have commented was a comet sighting recorded as having occurred in 12 BCE.

49) For the Qin-Western Han period, Liu Xiang shows some interest in anomalies happening in the period in which Qin rose to hegemonic status (starting ca. 350 BCE) prior to the establishment of the Han dynasty in 202 BCE. There is also a long period that corresponds to the reign of Thearch Wu (141-87 BCE) for which Liu Xiang is listed as having made comments on only three anomalies that are recorded as having occurred in this period. Based on the set of events for which it can be positively affirmed that Liu Xiang commented on, there is no evidence that Liu Xiang made a comprehensive catalogue of anomalies that were recorded as occurring in the whole of Western Han history.

In contrast to Set 1, Set 2 demonstrates a continuous, relatively even interest in anomalous events throughout the Western Han that does not feature the pronounced clustering that is present in Set 1. Set 2 also demonstrates observation of anomalies occurring in the last decades of the Western Han period, and even what might be interpreted as a somewhat pronounced interest in those last decades. This is a feature absent from Set 1, which tapers off after 25 BCE and terminates altogether as of 12 BCE. Set 2 was clearly compiled by someone who had a knowledge of the last years of the Western Han. Within Set 2, there is also a continuous recording of anomalies in the period of time corresponding to the reign of Thearch Wu, another feature that makes Set 2 distinct from Set 1. Another distinguishing feature is that Set 2 shows scant interest in cataloguing anomalies occurring in the period of Qin hegemony that came after ca. 350 BCE or in the Qin imperial period. Set 2 reflects a compiler who had a view of the entirety of the Western Han period through its last years and looked on it with an apparent desire for exhaustive and comprehensive inclusion of accounts of events recorded as occurring in that periodÔÇöas opposed to omitting for whatever reason particular periods of the Western Han. All of these features point to Ban Gu as the compiler of Set 2.

Conclusions

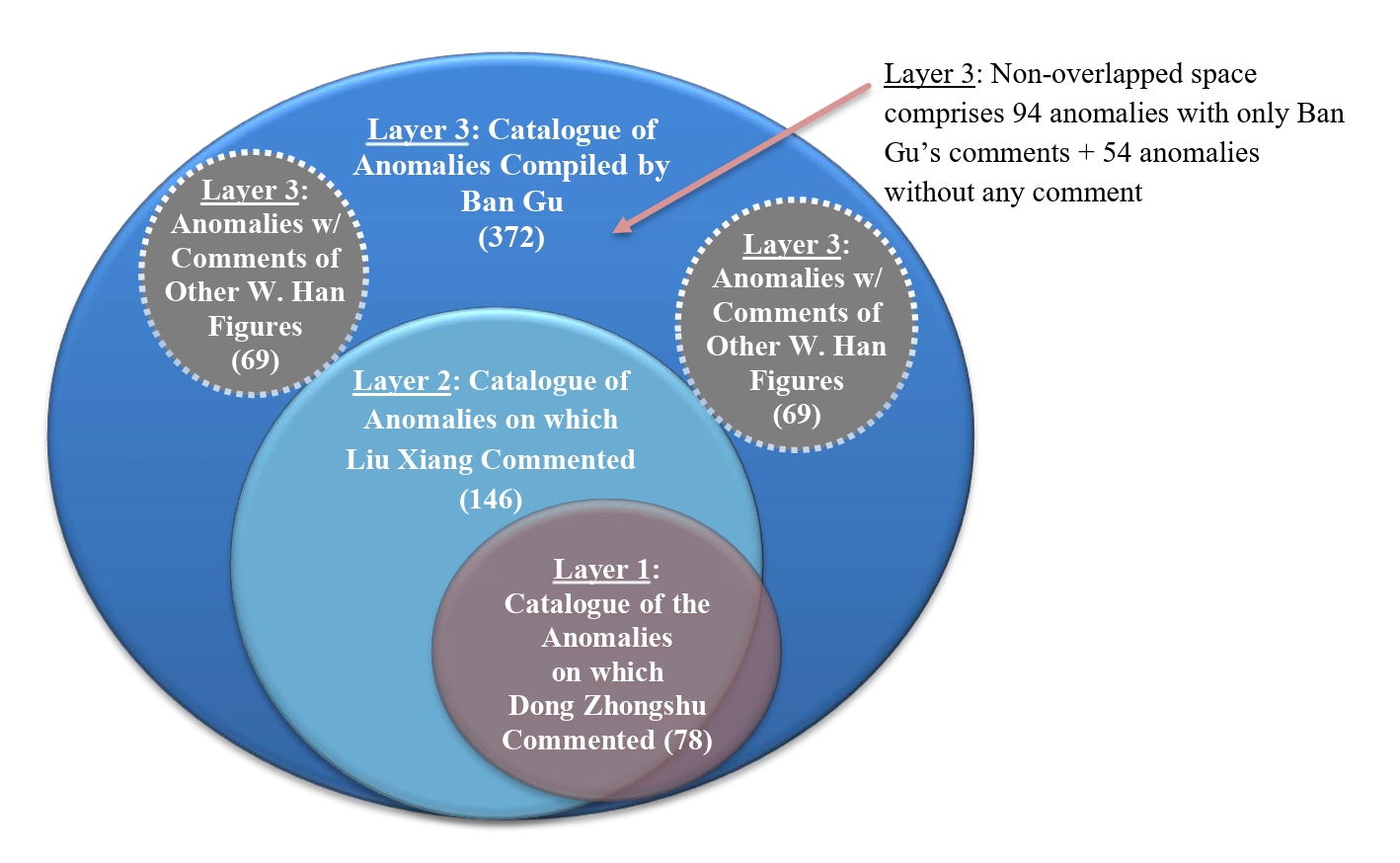

Based on the above analysis, it can be seen that while Ban Gu integrated into the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ a significant amount of content that was not originally authored by him, he also contributed a large amount of original content. Content originating from Dong Zhongshu comprised 78 accounts of anomalies (all but one of which were from the Chunqiu) with Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs comments on them. Content from Liu Xiang comprised approximately 146 accounts of anomalies (the majority of which were documented in the Chunqiu or its commentaries) and Liu XiangÔÇÖs comments on them. That a significant number (69) of the 146 anomalies that Liu Xiang commented on are among the 77 that Dong Zhongshu had commented on before him, suggests that the structure of Liu XiangÔÇÖs own catalogue seems to have originally been inspired and informed by Dong ZhongshuÔÇÖs own list. The basic idea of classifying anomalies from recorded history according to the theoretical and taxonomical schema of the Hong fan ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ also came from Liu Xiang (though Ban Gu likely was the first to present this way of viewing history in a systematic way with the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ). Ban GuÔÇÖs original contribution was to add another 148 accounts of anomalies (most of which were recorded as having occurred in the Western Han period) and give his own analysis of 94 of these based on Hong fan Wuxing zhuan theory. The contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ point to an accretive mode of textual production, whereby an author took an existing text and then expanded it by creatively added fresh content that was integrated into what already existed.

This stratigraphic reading of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is something of a simplified version of the structure made to demonstrate its basic, foundational framework. It would be remiss to overlook that a portion of the some 217 anomalies that Ban Gu added to the catalogues of Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang (and for which there is no record that Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang ever commented on) come with the comments of the other Western Han figures (Liu Xin ňŐëŠČú, Sui Meng šťşňşč, Xiahou ShengňĄĆńż»ňőŁ, Jing Fang ń║ČŠł┐, Gu Yong Ŕ░ĚŠ░Ş, and Li Xun ŠŁÄň░ő) whom Ban Gu names in the preface. Based on the difference between the 217 anomalies that Ban Gu added and the 148 that are uncommented or contain only Ban GuÔÇÖs comments, the number of such anomalies commented by other figures can be estimated as being about 69. This further demonstrates the composite nature of the text without lessening Ban GuÔÇÖs role as a compiler. The figure below (Figure 2) is a visualization of the three-layered structure of the ÔÇťWuxing zhi.ÔÇŁ Each successive layer encompasses (or largely encompasses) each layer before it. While this cannot be said to be an exhaustive view (Ban Gu in places may have appended the comments of those other Western Han figures to anomalies on which Dong Zhongshu or Liu Xiang had also commented), it at least offers an understanding of the basic framework of the text

.

Viewing the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ from this perspective deeply problematizes the view that the authors of its contents were intending their catalogue to be a critique of any particular ruler or number of rulers about whom they held prejudices. The logic followed by the three individuals who for the most part composed the contents of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ seems to have been to start from what anomalies were recorded in the historical record and then to try to make an argument for what corruption on the part of past political rulers had caused the anomalies. In the case of Liu Xiang, who commented on a number of anomalies that had happened in the space of his own lifetime, his a priori judgments about the behavior at the time may have spurred him to call attention to anomalies at the time, but for the most part, Liu Xiang was cataloguing anomalies that happened before (in many cases long before) his lifetime. Historical distance would likely in most cases have greatly reduced the urgency to call attention to past anomalies in order to criticize a particularly despised leader of the past. This is also certainly the case with Dong Zhongshu, who was preoccupied with the event of the Chunqiu and is recorded in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as commenting on only one anomaly that happened in his lifetime. Ban Gu, too, was for the most part (if not entirely) cataloguing anomalies that happened before his lifetime. The weight of the ÔÇťtendentious compiler of anomaliesÔÇŁ argument is greatly reduced by a stratigraphic view of the text.

Thinking of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as a record of dissatisfaction with Western Han rulers in the official class (as Bielenstein argues) becomes a more tenuous view as well. While contemporaneous act of recording individual anomalies in history may have been subject to certain tendencies (such as less intensive recording of anomalies in times of ÔÇťgood rulersÔÇŁ), there is no way of knowing for sure if the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ is an exhaustive representation of all anomalies that were entered into the Western Han historical record. Moreover, there are other reasons that anomalies might not have made it into the historical record, such as the possible repression of the recording of anomalies by rulers who monitored such things. In any event, stratigraphic analysis requires that one analyze each layer of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ separately.

Looking at the list of Western Han anomalies that Liu XiangÔÇÖs commented on, one notices a gap for the reign of Thearch Wu. This could mean a few different things: maybe in the lifetime of Liu Xiang, Thearch Wu was seen as such a successful ruler that it was not thought useful to point out anomalies that happened during his reign; or the cult of Thearch Wu was so great that it was taboo to engage in such critical analysis of his rule in the decades after his death when Liu Xiang was alive; or Liu Xiang was just not all that interested in the history of his reign. It is difficult to know for certain. For the Western Han anomalies that Ban Gu catalogued, the trend is different from BielensteinÔÇÖs analysis. There are two peaks in the number of recorded anomalies: one occupies the decades corresponding to the rule of Thearch Wu, and another the last decades of the Western Han. This may reflect the personal evaluation of Ban Gu, or dissatisfaction in Western Han societies in those periods, or else be a random trend that emerged in Ban GuÔÇÖs search through historical records for recorded anomalies. Again, it is difficult to know for certain. (Including the Western Han anomalies commented on by Liu Xiang also slightly levels the peaks in Ban GuÔÇÖs catalogue.) But for both Liu Xiang and Ban GuÔÇÖs catalogue, stratigraphic analysis must first be applied before proceeding.

Combined with this analysis, applying OccamÔÇÖs Razor to the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ suggests reading it with the view that Ban Gu describes in the preface, that is, that its contents were generated by authors who were looking through historical records in search of evidence to demonstrate the theory of ÔÇťheaven-human sentient response.ÔÇŁ Reading it in toto as a tendentious fabrication or as accretion of contemporaneous political opinion distracts from the idea that, based on all textual evidence within the ÔÇťWuxing zhi,ÔÇŁ its compilers, working at their separate points in time, were for the most part primarily interested in the idea that the material world has an inherent moral valence that punishes corrupt rulers and rewards virtuous ones. Stratigraphic analysis allows for a comprehensive analysis that takes into consideration what contents were generated at what time, and for each layer to be compared with what is known about the author of its contents. This approach, one that is steadily grounded in the substance of the text rather than unevidenced theories of the intentions of Western Han record keepers, reveals the text to be an embodiment of (and therefore an important source for) Han political and material philosophy, rather than deceptive hocus pocus.

Notes

Figure 1.

Comparison of Time Distribution of Defined Sets of Anomalous Events Listed in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as Having Occurred in the Qin-Western Han Period*

(Shown by Recorded Year of Occurrence)**

*Qin-Western Han period defined as Qin Hegemony / Imperial Period (ca. 350-202 BCE) and Western Han (202 BCE-8 C.E.)

**x-axes: recorded time of occurrence, shown in ten-year intervals; y-axes: number of anomalous occurrences recorded

Figure 2.Stratigraphic View of the Structure of the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ as 3 Layers

Table 1.No. of Anomalous Incidents Cited in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ (Tabulated by Source)

|

Source |

Number of Anomalous Incidents Cited |

|

CQ |

120 |

|

CQ/ZZ |

1 |

|

CQ/GLZ/GYZ |

1 |

|

ZZ |

18 |

|

SS |

2 |

|

SJ |

15 |

|

QHH |

214 |

|

Total

|

372

|

Table 2.No. of Anomalous Incidents Cited in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁto which Comments by Dong Zhongshu are Appended (Tabulated by Source)

|

Source |

Number of Anomalous Incidents Cited |

|

CQ |

77 |

|

QHH |

1 |

|

Total

|

78

|

Table 3.No. of Anomalous Incidents Cited in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ for which Comments by Liu Xiang are Appended (Tabulated by Source)

|

Period of Occurrence (as Based on Information Given in the Recorded Account) |

Source |

Number of Anomalous Incidents Cited |

|

Chunqiu Period (722-468 BCE) (including also events prior to the Chunqiu period) |

SS |

2 |

|

CQ |

93 |

|

ZZ |

9 |

|

SJ |

5 |

|

Qin Hegemony / Imperial Period (ca. 350-202 BCE) and Western Han (202 BCE-8 C.E.) |

SJ |

4 |

|

QHH |

33 |

|

Total

|

146

|

Table 4.

Wuxing zhuan Terms Used by Liu Xiang

|

Term(s) |

Citation |

|

ÔÇťeerie occurrence in plantsÔÇŁ ŔŹëňŽľ |

HS, 1409. |

|

ÔÇťeerie occurrence in clothingÔÇŁ ŠťŹňŽľ (x2) |

HS, 1366; 1366. |

|

ÔÇťsounded eerie occurrenceÔÇŁ Ú╝ôňŽľ |

HS, 1428. |

|

ÔÇťeerie occurrence in dartsÔÇŁ ň░äňŽľ |

HS, 1463. |

|

ÔÇťeerie occurrence in dartsÔÇŁ ň░äňŽľ / ÔÇťblack salient deviationÔÇŁ Ú╗Ĺšąą |

HS, 1463 |

|

ÔÇťabnormality in fishÔÇŁ ÚşÜňşŻ |

HS, 1430. |

|

ÔÇťabnormality in dragons and snakesÔÇŁ ÚżŹŔŤçňşŻ |

HS, 1465. |

|

ÔÇťabnormality in creatures that have a hard shellÔÇŁ ń╗őŔč▓ń╣őňşŻ |

HS, 1431. |

|

ÔÇťabnormality in dragonsÔÇŁ ÚżŹňşŻ |

HS, 1466. |

|

ÔÇťabnormality in snakesÔÇŁ ŔŤçňşŻ (x2) |

HS, 1467; 1468. |

|

ÔÇťstartling malady in horsesÔÇŁ ÚŽČšŽŹ(ŠŚĄ) |

HS, 1469. |

|

ÔÇťstartling malady in chickensÔÇŁ ÚĚ䚎Ź(ŠŚĄ) |

HS, 1369. |

|

ÔÇťstartling malady in pigsÔÇŁ Ŕ▒ĽšŽŹ(ŠŚĄ) |

HS, 1436. |

|

ÔÇťstartling malady in cowsÔÇŁ šëŤšŽŹ(ŠŚĄ) (x3) |

HS, 1447; 1447; 1448. |

|

ÔÇťstartling malady in cowsÔÇŁ šëŤšŽŹ(ŠŚĄ) / ÔÇťgreen salient deviationÔÇŁ ÚŁĺšąą |

HS, 1373. |

|

Table 4 (Continued):

|

Table 4 (Continued):

|

|

ÔÇťgreen aberrant generationÔÇŁ ÚŁĺšťÜ |

HS, 1431-32. |

|

ÔÇťgreen aberrant generationÔÇŁ ŔÁĄšťÜ (x2) |

HS, 1420; 1420. |

|

ÔÇťstartling maladyÔÇŁ šťÜ / ÔÇťsalient deviationÔÇŁ šąą |

HS, 1414. |

|

ÔÇťwhite salient deviationÔÇŁ šÖŻšąą |

HS, 1340. |

|

ÔÇťgreen salient deviationÔÇŁ ÚŁĺšąą (x2) |

HS, 1396; 1417. |

|

ÔÇťwhite and black salient deviationÔÇŁ šÖŻÚ╗Ĺšąą |

HS, 1415. |

|

ÔÇťmetal disrupting woodÔÇŁ ÚçĹŠ▓┤ŠťĘ |

HS, 1375. |

|

ÔÇťfire disrupting waterÔÇŁ šüźŠ▓┤Š░┤ (x2) |

HS, 1437; 1438. |

|

ÔÇťwater disrupting earthÔÇŁ Š░┤Š▓┤ňťč |

HS, 1457. |

|

ÔÇťmetal, wood, water, and fire disrupting earthÔÇŁ ÚçĹŠťĘŠ░┤šüźŠ▓┤ňťč |

HS, 1451. |

Table 5.No. of Anomalous Incidents Cited in the ÔÇťWuxing zhiÔÇŁ That Contain Either No Comments or Only Comments Without Attribution (Tabulated by Source)

|

Period of Occurrence (as Based on Information Given in the Recorded Account) |

Source |

Number of Anomalous Incidents Cited |

|

Chunqiu Period (722-468 BCE) |

CQ |

19 |

|

ZZ |

6 |

|

SJ |

2 |

|

Qin Hegemony / Imperial Period (ca. 350-202 BCE) and Western Han (202 BCE-8 C.E.) |

SJ |

2 |

|

QHH |

119 |

|

Total

|

148

|

|

(Of total, uncommented) |

54 |

|

(Of total, with only unattributed comments) |

94 |

- Ban Gu šĆşňŤ║et al. Han shu Š╝óŠŤŞ. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962 [22nd printing, 2019].

- Bielenstein, Hans. ÔÇťAn Interpretation of the Portents in the TsÔÇÖien-Han-Shu.ÔÇŁ Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 22 (1950): 127-43.

- Cai, Liang. ÔÇťThe Hermeneutics of Omens: The Bankruptcy of Moral Cosmology in Western Han China (206 BCE-8 CE).ÔÇŁ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 25, no.3 JulýŤö (2015): 439-459.

- Chen Kanli ÚÖ│ńżâšÉć. Zaiyi de zhengzhi wenhua shi: Ruxue shushu yu zhengzhi šüŻšĽ░šÜäŠö┐Š▓╗ŠľçňîľňĆ▓:ňäĺňşŞŠĽŞŔíôŔłçŠö┐Š▓╗. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2015.

- Cheng Sudong šĘőŔśçŠŁ▒. Han dai ÔÇťHong fanÔÇŁ Wuxing xue Š╝óń╗úŠ┤¬š»äń║öŔíîňşŞ. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2023.

- Durrant, Stephen, Wai-yee Li, and David Schaberg, eds., and trans. Zuo Tradition. 3 Vols. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.

- Eberhard, Wolfram. Beitr├Ąge zur kosmologischen Spekulation der Chinesen der Han-Zeit. Ph.D. diss., University of Berlin, 1933.

- ____. ÔÇťBeitr├Ąge zur Astronomie der Han-Zeit II.ÔÇŁ Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische Klasse (1933): 937-79.

- ____. ÔÇťNeuere Chinesische und Japanische Arbeiten zur altchinesischen Astronomie.ÔÇŁ Asia Major 9 (1933): n.p.

- ____. ÔÇťPolitical Function of Astronomy and Astronomers in Han China.ÔÇŁ In John K. Fairbank, Robert Redfield, and Milton B. Singer, eds., Chinese Thought and Institutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957, pp. 33-70.

- Graham, A.C. Disputers of the Tao. Chicago and Lasalle, Illinois: Open Court Press, 2003.

- Homer H. Dubs., trans. and ed. The History of the Former Han Dynasty, Vol. 1. Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1938.

- Ikeda Tomohisa Š▒ášö░ščąń╣ů. ÔÇťCh┼źgoku godai no tenjin s┼Źkan non: T┼Ź Ch┼źjyo no b─üiÔÇŁ ńŞşňŤŻňĆĄń╗úŃü«ňĄęń║║šŤŞÚľóŔźľÔÇöŔĹúń╗▓ŔłĺŃü«ňá┤ňÉł. In Mizoguchi Y┼źs┼Ź Š▓čňĆúÚŤäńŞë, Hamashita Takeshi Š┐▒ńŞőŠşŽň┐Ś, Hiraishi Naoaki ň╣│šč│šŤ┤Šśş, and Hiroshi Miyajima ň««ňÂőňŹÜňĆ▓, eds., Ajia kara kangaeru sekaiz┼Ź no keisei ŃéóŃéŞŃéóŃüőŃéëŔÇâŃüłŃéőńŞľšĽîňâĆŃü«ňŻóŠłÉ. Tokyo: T┼Źkyo daigaku shuppanshya, 1994, pp. 9-75.

- Kim Dongmin ŕ╣ÇŰĆÖŰ»╝. ÔÇťTong Chungso ChÔÇÖunÔÇÖgyuhak ┼şi chÔÇÖ┼Ćnin kam┼şngnon e taehan kochÔÇÖalÔÇösangso chayi s┼Ćr ┼şl chungsim ┼şroÔÇŁ ŔĹúń╗▓Ŕłĺ ŠśąšžőňşŞýŁś ňĄęń║║ŠäčŠçëŔźľýŚÉ ŰîÇÝĽť ŕ│áý░░ÔÇöšąąšĹךüŻšĽ░Ŕ¬¬ýŁä ýĄĹýőČýť╝Űíť. Tongyang Ch'┼Ćrhak Y┼Ćn'gu ŠŁ▒Š┤őňô▓ňşŞšáöšęÂ, 36 (2004): 313-48.

- Nylan, Michael. ÔÇťA Modest Proposal, Illustrated by the Original ÔÇśGreat PlanÔÇÖ and Han Readings.ÔÇŁ Cina No 21 (1988): 251-264.

- ____. The Shifting Center: The Original ÔÇťGreat PlanÔÇŁ and Later Readings. Institut Monumenta Serica in Sankt Augustin and Nettetal in Steyler Verlag, 1992.

- ____. ÔÇťOn Hanshu ÔÇśWuxing zhiÔÇÖ ń║öŔíîň┐Ś and Ban GuÔÇÖs Project.ÔÇŁ In Mark Csikszentmihalyi and Michael Nylan, eds. Technical Arts in the Han Histories: Tables and Treatises in the Shiji and Hanshu. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2021, pp. 213-79.

- Puett, Michael. ÔÇťViolent Misreadings: The Hermeneutics of Cosmology in the Huainanzi.ÔÇŁ Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 72 (2000): 29-47.

- Ruan Yuan Úś«ňůâ, ed. Chong kan Song ben Gongyang zhushu fu jiaokan ji ÚçŹňłŐň«őŠťČňůČšżŐŠ│ĘšľĆÚÖäŠáíňőśŔĘś. Nanchang: Nanchang fu xue ňŹŚŠśîň║ťňşŞ, Jiaqing ershi nian ňśëŠůÂń║îňŹüň╣┤ [1815]. Rpt. in Ruan ke Chunqiu Gongyang zhuan zhushu Úś«ňůâňł╗ŠśąšžőňůČšżŐňé│Š│ĘšľĆ. Hangzhou: Zhejiang daxue chubanshe, 2020.

- ____. Chong kan Song ben Guliang zhushu fu jiaokan ji ÚçŹňłŐň«őŠťČšęÇŠóüŠ│ĘšľĆÚÖäŠáíňőśŔĘś. Nanchang: Nanchang fu xue ňŹŚŠśîň║ťňşŞ, Jiaqing ershi nian ňśëŠůÂń║îňŹüň╣┤ [1815]. Rpt. in Ruan ke Chunqiu Guliang zhuan zhushu Úś«ňůâňł╗ŠśąšžőšęÇŠóüňé│Š│ĘšľĆ. Hangzhou: Zhejiang daxue chubanshe, 2020.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. ÔÇťShang shu ň░ÜŠŤŞ (Shu ching ŠŤŞšÂô).ÔÇŁ In Michael Loewe, ed. Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 1993, pp. 376-89.

- Wang Aihe šÄőŠäŤňĺî. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Yang Bojun ŠąŐń╝»ň│╗. Chunqiu Zuo zhuan zhu ŠśąšžőňĚŽňé│Š│Ę. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1981 [21st printing: 2020].

- Yang Shao-yun. ÔÇťThe Politics of Omenology in ChengdiÔÇÖs Reign.ÔÇŁ In Michael Nylan and Greit Vankeerberghen, eds. ChangÔÇÖan 26 BCE: An Augustan Age in China. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2015, pp. 323-46.