Abstract

Wang Xizhi ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗ (ca. 303-ca. 361), the paragon calligrapher of the Eastern Jin dynasty, became a canonized figure in Chinese cultural history, particularly after Emperor Taizong of the Tang obsessively collected and reproduced his works. At that time, thus, one main criteria for ideal calligraphy was its resemblance to WangŌĆÖs style. In this context, stele inscriptions emerged that were composed by collecting, comparing, and imitating individual characters from WangŌĆÖs extant corpusŌĆöa practice known as ŌĆ£Collating CharactersŌĆØ ķøåÕŁŚ. One notable example in Korea is the Memorial Stele for Enshrining the Amit─übha Buddha Statue at Mujangsa Temple ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ķś┐ÕĮīķÖĆõĮøķĆĀµłÉĶ©śńóæ(801). Controversy has surrounded its calligraphic origins, however. In 1803, the prominent Qing scholar Weng Fanggang ń┐üµ¢╣ńČ▒ (1733ŌĆō1818) stated that the steleŌĆÖs calligraphy was modeled on the Dingwu edition (1041) of the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion. In contrast, his son Weng Shukun ń┐üµ©╣Õ┤æ (1786-1815) and the Korean antiquarian Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£ (1786ŌĆō1856) maintained the traditional view, i.e., the brushwork to Kim Yukchin ķćæķÖĖńÅŹ (fl. tenth century), a Silla calligrapher. This case study of the Mujangsa Stele examines how the same inscription was interpreted differently by scholars in China and Korea, revealing divergent frameworks of copying, authenticity, and cultural authority. It then turns to ongoing debates among modern scholars, proposing that the two seemingly opposing theoriesŌĆöcollation versus Korean inscriberŌĆömay in fact be complementary rather than contradictory.

-

Keywords: Wang Xizhi ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗ, Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, Preface to Sage Teachings, Mujangsa Stele, Weng Fanggang ń┐üµ¢╣ńČ▒, Weng Shukun ń┐üµ©╣Õ┤æ, Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£, Kim Yukchin ķćæķÖĖńÅŹ, Collating Characters ķøåÕŁŚ

Among Korean inscriptions praised in China, none has been held in higher esteem than this stele.

µØ▒µ¢╣µ¢ćńŹ╗õ╣ŗĶ”ŗń©▒µ¢╝õĖŁÕ£ŗ, ńäĪÕ”éµŁżńóæ.

Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi, 1817

Introduction*

Wang Xizhi ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗ (ca. 303ŌĆōca. 361) and his calligraphy were introduced to Korea through diplomatic exchanges during the formation of early SillaŌĆōTang relations.

1 In 648, during the mission of Kim ChŌĆÖunchŌĆÖu ķćæµśźń¦ŗ (602ŌĆō661) to the Tang courtŌĆöundertaken to secure a military alliance against Kogury┼Å (37? BCEŌĆō668 CE)ŌĆöEmperor Taizong (r. 626-649) bestowed upon him two calligraphic works of the

Hot Spring Stele µ║½µ╣»ńóæ (i.e. µ║½µ│ēķŖś) and the

Jin Shrine Stele µÖēńźĀńóæ, both composed and inscribed by the emperor himself in the style of Wang Xizhi. Roughly a century later, Wang XizhiŌĆÖs style gained a wide currency among Korean calligraphers. Kim Saeng ’żŖńö¤ (b. 711) was particularly celebrated for his mastery of Wang-style calligraphy. One anecdote illustrates the high technical and aesthetic regard in which KimŌĆÖs work was held and simultaneously, Chinese lack of that recognition.

During the Chongning era (1102ŌĆō1106), Academician Hong Kwan µ┤¬ńüī (d. 1126) traveled to the Song dynasty capital of Bianjing (modern Kaifeng, Henan) as part of a diplomatic mission. While residing at the Guest Hall, he was visited by Hanlin Academicians Yang Qiu µźŖńÉā and Li Ge µØÄķØ®, who had been dispatched by imperial order. As the two men took up their brushes to compose on a scroll, Hong presented them with hanging scrolls of cursive and semicursive calligraphy by Kim Saeng. Their dialogue began:

2

ŌĆ£We did not expect to behold original works by Wang Xizhi today,ŌĆØ the two exclaimed in astonishment. ŌĆ£These are not by Wang Xizhi,ŌĆØ Hong replied. ŌĆ£They are the work of Kim Saeng, a man of Silla.ŌĆØ The two laughed and said, ŌĆ£Apart from the works of Wang Xizhi, how could such marvelous calligraphy exist in this world?ŌĆØ Hong explained it several times, but they did not believe it to the end.

õ║īõ║║Õż¦ķ¦Łµø░: ŌĆ£’ź¦Õ£¢õ╗ŖµŚźÕŠŚĶ”ŗńÄŗÕÅ│Ķ╗ŹµēŗµøĖ.ŌĆØ µ┤¬ńüīµø░: ŌĆ£ķØ×µś», µŁżõ╣āµ¢░ńŠģõ║║’żŖńö¤µēƵøĖõ╣¤.ŌĆØ õ║īõ║║ń¼æµø░: ŌĆ£Õż®õĖŗķÖżÕÅ│Ķ╗Ź, ńäēµ£ēÕ”ÖńŁåÕ”éµŁżÕōē.ŌĆØ µ┤¬ńüīÕ▒óĶ©Ćõ╣ŗ, ńĄé’ź¦õ┐Ī.

This exchange occurred during the early reign of Emperor Huizong (r. 1100ŌĆō1125), a period marked by a revivalist zeal for antiquity and imperial enthusiasm for collecting paintings and calligraphy. Like Emperor Taizong of Tang, Huizong avidly sought works attributed to Wang Xizhi and made them copied. At a time when even the most accomplished Chinese calligrapher struggled to emulate WangŌĆÖs style convincingly, the two Chinese scholars could not accept the possibility that a non-Chinese calligrapher could have produced such work. This anecdote highlights not only the technical brilliance of Kim SaengŌĆÖs calligraphy, but also the deeply rooted Sinocentric view that artistic excellence was presumed to be coterminous with Chinese cultural identity.

However, it would be an overgeneralization to treat a single anecdote as definitive evidence of Chinese underestimation of Korean calligraphy. In fact, there were also voices of admiration for Kim Saeng. Zhao Mengfu ĶČÖÕŁ¤ķĀ½ (1254ŌĆō1322), a master calligrapher of the Yuan dynasty, offers high praise for the Korean master in his ŌĆ£Postface to the

ChŌĆÖangnimsa SteleŌĆØ µśīµ×ŚÕ»║ńóæĶĘŗ: ŌĆ£[In KimŌĆÖs calligraphy] the structure and brushwork of the characters are profoundly exemplary. Even renowned Tang inscriptions cannot easily surpass it. As the old saying goes, ŌĆśIs there any land that does not produce talent?ŌĆÖ Truly, it is so.ŌĆØ

3

ZhaoŌĆÖs parallel between KimŌĆÖs inscription and the masterpieces of Tang China is notable, as it places the Korean work within the highest ranks of the Chinese calligraphic canon. The adage he invokes encapsulates a cosmopolitan vision of artistic excellenceŌĆöone that transcends national boundaries and challenges the notion of Chinese cultural exclusivity. ZhaoŌĆÖs colophon thus functions not only as an aesthetic appraisal but also as a significant acknowledgment of non-Chinese contributions to the broader tradition of East Asian calligraphy. Unfortunately, most of KimŌĆÖs calligraphy, including the ChŌĆÖangnimsa Stele, no longer survives, making further in-depth study difficult.

More significant than Kim SaengŌĆÖs calligraphy in Sino-Korean calligraphic discourse is the

Memorial Stele for Enshrining the Amit─übha Buddha Statue at Mujang Temple ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ķś┐ÕĮīķÖĆõĮøķĆĀµłÉĶ©śńóæ (hereafter

Mujangsa Stele). Mujangsa Temple was situated north of AmgokchŌĆÖon µÜŚĶ░ʵØæ, in the northeastern region of Ky┼Ångju. Its remote location was a deliberate choice, intended to mark a clear boundary between the sacred Buddhist domain and the secular world. In 801, one year after the death of her husband, King Sos┼Ång (r. 799ŌĆō800), Queen Kyehwa commissioned a statue of Amit─übha Buddha in devotion, to ensure his rebirth in the Pure Land, and erected a commemorative stele to document its construction.

4

Chosŏn Neo-Confucian scholars turned little attention to the

Mujangsa Stele. Long forgotten and even broken into pieces, it was rediscovered in 1770 by Hong Yangho µ┤¬Ķē»µĄ® (1724ŌĆō1802). During his tenure as magistrate of Ky┼Ångju, he launched a determined search and ultimately recovered a major fragment near the temple site. The steleŌĆÖs reappearance drew significant attention due to its striking resemblance to the calligraphic style of Wang Xizhi, prompting fundamental questions about the reproduction and transmission of calligraphic models across cultural and national boundaries. The inscription had traditionally been attributed to Kim Yukchin ķćæķÖĖńÅŹ (fl. 10th century),

5 but Weng Fanggang ń┐üµ¢╣ńČ▒ (1733ŌĆō1818) offered a new and controversial theory: the stele was a case of

chipcha (Ch.

jizi ķøåÕŁŚ)ŌĆöthat is, the characters were collated directly from Wang XizhiŌĆÖs works.

The term collating characters refers to a uniquely Sinographic practice found primarily in China and Korea. Rooted in the reverence for proper script forms and refined calligraphic styles, this practice involved modeling oneŌĆÖs writing on the works of ancient mastersŌĆömost notably Wang Xizhi. Practitioners compiled individual characters from WangŌĆÖs extant corpus and reassembled them to transcribe an entirely new text. In instances where the desired character was missing, they would draw upon morphologically similar components from different characters, sometimes combining elements from various periods of WangŌĆÖs lifeŌĆöincluding presumed posthumous forgeries.

Interpreting calligraphic style often involves cultural implications. Previously, the

Mujangsa Stele had been considered a brushwork of Kim Yukchin or another Silla figure, and this ŌĆ£inscriber theoryŌĆØ (

s┼Åjas┼Ål µøĖÕŁŚĶ¬¬) suggests not only the adoption of WangŌĆÖs style but also its internalization and creative transformation by a Silla calligrapher. Though perhaps not equal to Wang XizhiŌĆöthe revered ŌĆ£Sage of CalligraphyŌĆØ µøĖĶü¢ŌĆöthis calligrapher demonstrated a level of mastery comparable to Tang dynasty copiers of WangŌĆÖs script. In contrast, Weng FanggangŌĆÖs ŌĆ£collating charactersŌĆØ theory may be read as affirming the enduring influence of Chinese cultural authority. Although collated inscriptions still reflect the individuality of the person assembling the characters,

6 the act of collation inevitably entails a higher degree of imitation than original composition. Thus, debates over the script of the

Mujangsa Stele have become a key issue in the history of Korean calligraphy, closely intertwined with questions of cultural agency and the legacy of Sinocentrism in East Asian exchange.

Against this background, the present study examines how the

Mujangsa SteleŌĆÖs calligraphic style was interpreted by Qing and Chos┼Ån literati, focusing on Weng Fanggang, Weng Shukun ń┐üµ©╣Õ┤æ (1786-1815), and Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£ (1786ŌĆō1856). While previous research has primarily discussed historical context and issues of cultural centrism,

7 this paper shifts the focus toward the theoretical and practical aspects of collating characters.

One major challenge in this discourse is that traditional scholars often fail to provide clear justifications for their interpretations. An exception is Weng Fanggang, who points to the presence of three dots as evidence for his theory; most others, however, make assertions without offering any substantial reasoning. In its final section, therefore, the paper offers a critical review of modern scholarly debates, centering on Lee Eun-Hyuk and Jung Hyun-sook. They respectively represent the conventional view of the inscriber and the new theory of collating characters. In conclusion, I propose a reconciliatory perspective, suggesting that a synthesis of the two approaches is not only possible, but also productive for understanding the calligraphic complexity and ramifications of the Mujangsa Stele.

New Approach: Weng Fanggang and the Character sung Õ┤ć

Weng Fanggang was an eminent scholar and collector of rare rubbings and stone inscriptions. In 1779, for example, he acquired the inscription from the Sarira Pagoda of Chan Master Yong ķéĢń”¬ÕĖ½ĶłŹÕł®ÕĪöķŖś, which was written by Li Boyao µØÄńÖŠĶŚź (565-648) and inscribed by Ouyang Xun µŁÉķÖĮĶ®ó (557-641) in 631. In celebration of this rubbing, Weng named his studio ŌĆ£the House of Stone and InkŌĆØ (

shimo shulou ń¤│Õó©µøĖµ©ō).

8 His antiquarian interests extended to Korea, as evidenced by his authorship of three postscripts to early Korean steles.

9 Among these, the

Mujangsa Stele attracted his greatest attention, owing to its perceived connection with the calligraphic style of Wang Xizhi. As a specialist in the

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion ĶśŁõ║ŁÕ║Å, Weng was able to identify traces of Wang XizhiŌĆÖs influence without difficulty. Furthermore, Weng offered the controversial theory of ŌĆ£collating characters.ŌĆØ

10

The [Mujangsa] steleŌĆÖs semicursive scripts come from a mixture of the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion and characters collated by the monks Huairen and Daya. Since the Xianheng (670-674) and Kaiyuan (713-741) reigns of Tang, source materials collated [by Huairen and Daya] had been influential so that people of foreign countries practiced them. The characters they used from the Preface all matched the Dingwu edition. Therefore, we know that the edition was truly carved at the time of the Tang and thereafter it spread abroad during the same period.

ńóæĶĪīµøĖ, ķø£ńö©ÕÅ│Ķ╗ŹĶśŁõ║ŁÕÅŖµćĘõ╗üÕż¦ķøģµēĆķøåÕŁŚ. ĶōŗĶć¬ÕÆĖõ║©ķ¢ŗÕģāõ╗źõŠå, ÕöÉõ║║ķøåÕÅ│Ķ╗ŹµøĖ, Õż¢Õ£ŗńÜåń¤źµ£Źń┐ÆĶĆīµēĆńö©ĶśŁõ║ŁÕŁŚ, ńÜåĶłćիܵŁ”µ£¼ÕÉł. õ╣āń¤źÕ«ÜµŁ”µ£¼Õ»”µś»ÕöɵÖéµēĆÕł╗, ÕøĀµĄüµÆŁµ¢╝ńĢȵÖéĶĆ│.

By the early Tang, Wang XizhiŌĆÖs original works were already scattered, prompting Emperor Taizong to obsessively collect and reproduce them. When the emperor composed the

Preface to the Sage Teaching of Tripiß╣Łaka of Great Tang Õż¦ÕöÉõĖēĶŚÅĶü¢µĢÄÕ║Å in celebration of XuanzangŌĆÖs ńÄäÕźś (602-664) translation of Buddhist Sutras, the monk Huairen (fl. seventh century) collated characters from Wang XizhiŌĆÖs works to produce the stele inscription at Hongfusi Temple Õ╝śń”ÅÕ»║ in 672. Roughly fifty years later, in 721 another monk Daya (fl. eighth century) employed the same method to erect a similar stele at Xingfusi Temple Ķłłń”ÅÕ»║

.

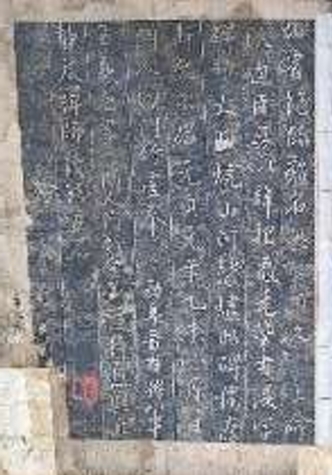

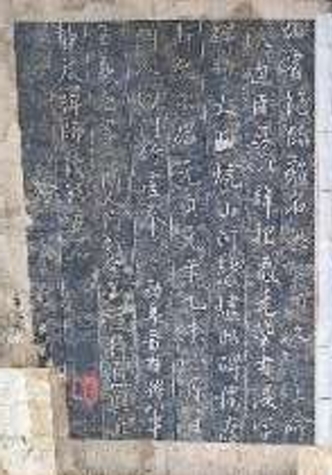

More importantly, the emperor ordered Ouyang Xun to engrave the inscription of the

Preface to the Orchid Pavillion on a stele, but it disappeared during the turbulent Tang-Song transitional period. Later, sometime between 1041 and 1048, Li Xuejiu µØÄÕŁĖń®Č found it at Dingwu իܵŁ” (modern Dingzhou Õ«ÜÕĘ×, Hebei province)ŌĆöthus it is called the Dingwu edition, but it was lost again after the fall of the Northern Song. The earliest extant rubbing of the Dingwu stele is a Song edition, now held in the National Palace Museum in Taipei (See

Figure 2). While rubbings of the Dingwu stele were initially regarded as authentic, their credibility came under scrutiny due to the proliferation of derivative copies in later periods. As such, Weng Fanggang drew attention to the

Mujangsa Stele for its stylistic resonance with the Dingwu edition and thus claimed the authenticity of the Dingwu edition through the Silla stele.

In 1803, Weng commented on the character

sung Õ┤ć, noting its stylistic affinity with the character

chong Õ┤ć in WangŌĆÖs works: ŌĆ£The three dots below the mountain radical (

shan Õ▒▒) in the character

chong are fully preserved.ŌĆØ

11 This statement is difficult to understand without background explanation. It is thus necessary to first examine, through visual comparison, the forms of the character as it appears in the

Mujangsa Stele and in WangŌĆÖs works.

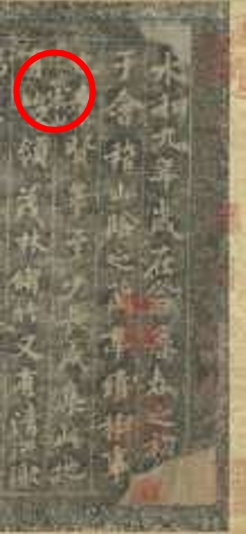

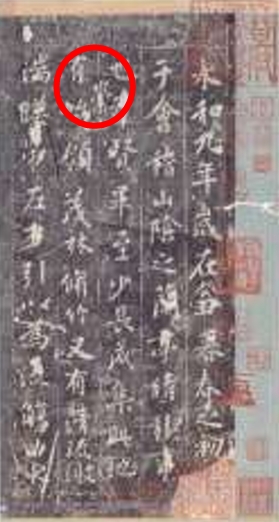

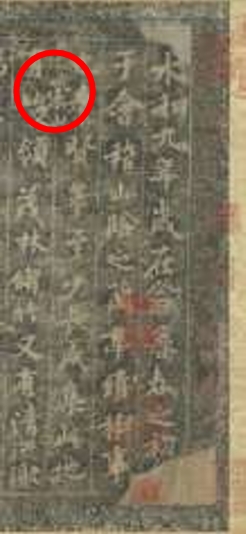

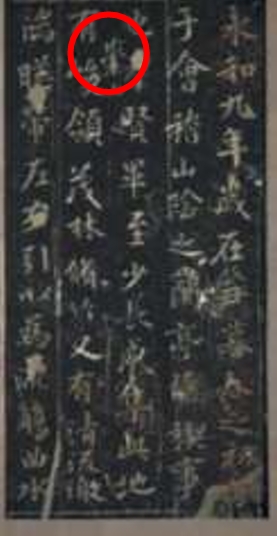

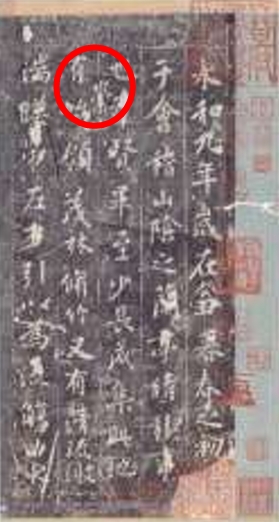

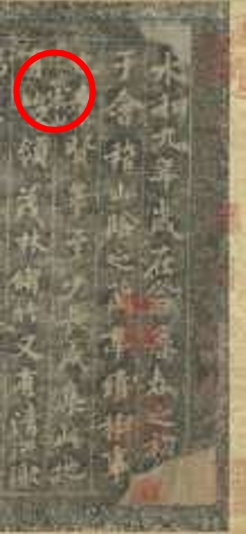

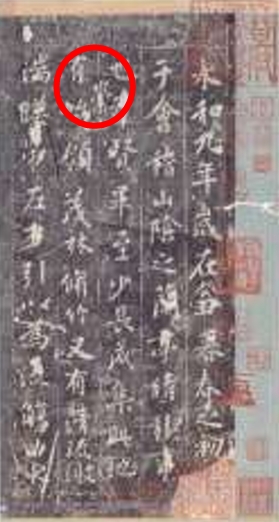

The character sung appears three times in the Mujangsa Stele, and each instance is rendered somewhat differently to avoid monotony, based on the calligraphic principle of ŌĆ£varied forms of the same characterŌĆØ ÕÉīÕŁŚńĢ░ÕĮó. Among the three variants, the one that Weng Fanggang noted for its ŌĆ£three dotsŌĆØ õĖēķ╗× appears in the second instance. The three dots are visible beneath the san Õ▒▒ radical.

In the inscription of the

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, the character

chong is relatively easy to identify; the word chongshan Õ┤ćÕ▒▒ appears as a later addition inserted into the upper section of the fourth column. Among the numerous extant reproductions of the

Preface, the character

chong with three dots is observed in two editions of Dingwu editions and more distinctly in the Yuquan ńÄēµ│ē edition (See

Figures 2,

3, and

4).

12 They likely informed WengŌĆÖs recognition of the

Mujangsa SteleŌĆöparticularly the character

chong and its Wang-style.

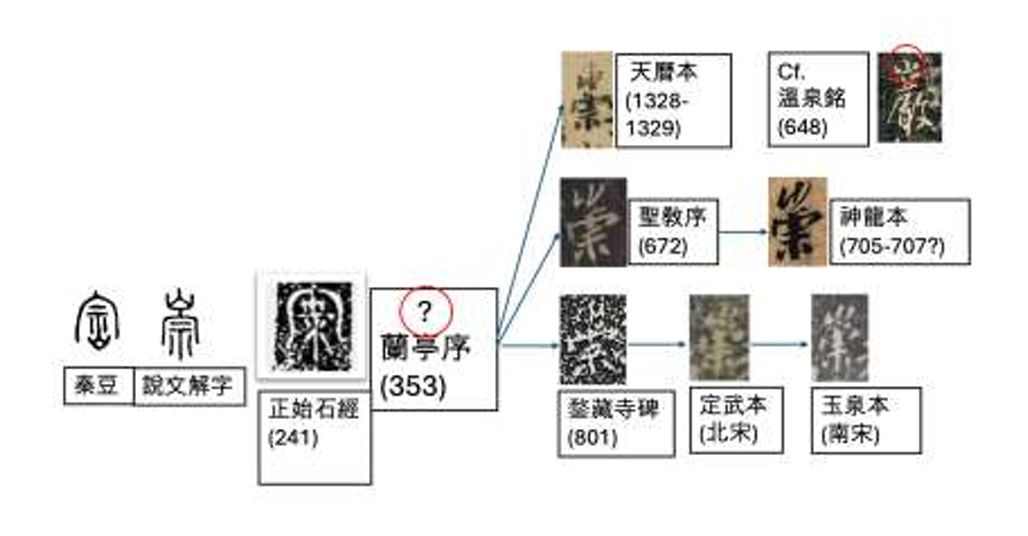

Since the original copy of the

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion already disappeared during the Tang period, it is ultimately impossible to know how Wang Xizhi actually wrote the character

chong. In his

Su-Mi zhai Lanting kao Ķśćń▒│ķĮŗĶśŁõ║ŁĶĆā, Weng Fanggang conducted a comprehensive examination of all available editions and documented the various forms of the character

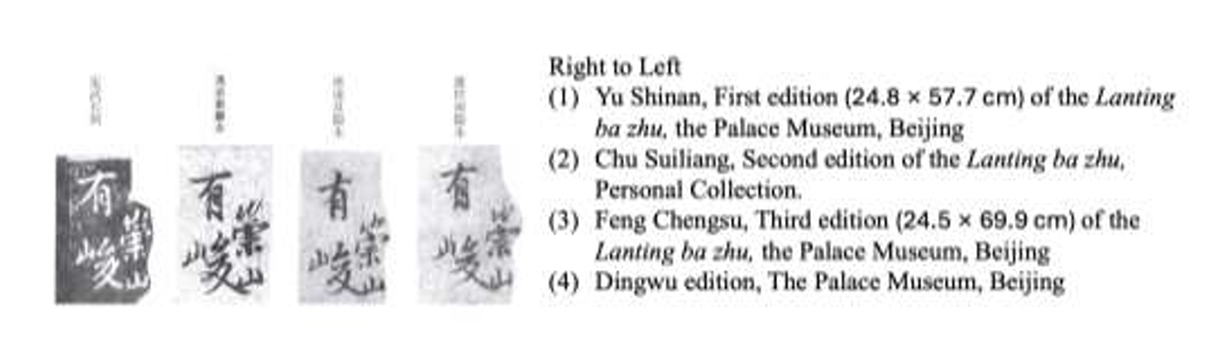

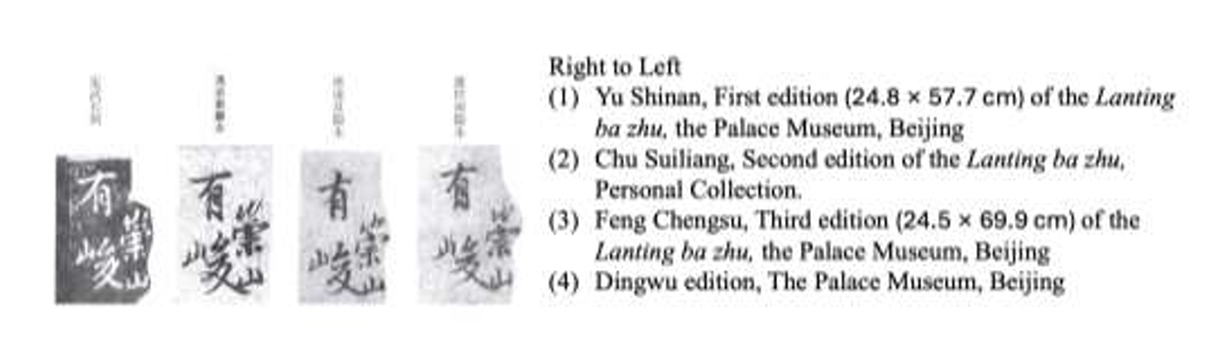

chong Õ«Ś. In the standard cursive script, the character has no dot beneath the mountain radical Õ▒▒. However, depending on the edition, a single central dot, a short horizontal stroke to the right, or a set of three dots may be added beneath the radical. The character variants are illustrated as follows

.

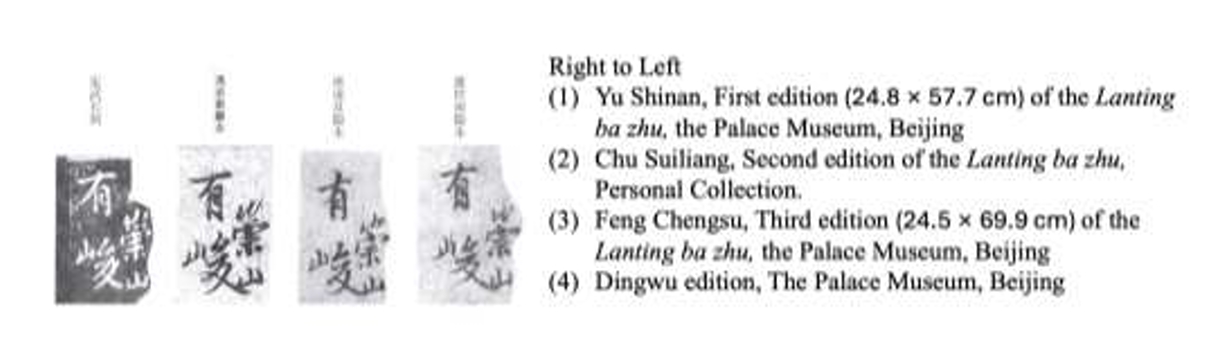

The first three rubbings are copies of works by Yu Shinan ĶÖ×õĖ¢ÕŹŚ (558ŌĆō638), Chu Suiliang ĶżÜķüéĶē» (597-658), and Feng Chengsu ķ”«µē┐ń┤Ā (617ŌĆō672), respectively, and were collected by Emperor Qianlong as the first, second, and third editions of the

Eight Pillars of the Lanting Preface (

Lanting bazhu ĶśŁõ║ŁÕģ½µ¤▒). The first, known as the Zhang Jinjie edition Õ╝ĄķćæńĢīÕź┤µ£¼, was copied during the Tianli Õż®µøå era (1328ŌĆō1329) and features an additional dot beneath the three strokes of the mountain radical. The second, regarded as the standard cursive form, consists of only the three original strokes. The third, the Shenlong edition ńź×ķŠŹµ£¼, contains a short horizontal stroke instead. The fourth and final example is the Dingwu edition, which features the distinctive three-dot form. Since our primary concern is with the three-dot variant, I will focus on the Dingwu edition in comparison with the others

.

The one dot in the Tianli edition is understood as the variation of the cursive script of the character. Nishikawa suggests that this is a distinctive trait of Wang XizhiŌĆÖs style. Influenced by Wang Xizhi, Emperor Taizong added one dot as a part of the mountain radical in the character

yan ÕĘ¢ in the

Inscription of Hot Spring. In the second linage of the Shenlong edition, a short horizontal stroke is not a variation of the upper dot in the character

zong Õ«ŚŌĆöwhich is already present as a prominent central vertical stroke. It is therefore understood as an additional and anomalous stroke of the mountain radical.

13 Nishikawa also explains that the dot is transformed into a small horizontal stroke, placed awkwardly and imbalancedŌĆöentirely detached from the three vertical lines, while the three vertical strokes forming the

shan Õ▒▒ radical appear unnatural in structure.

14

In my interpretation, however, the short horizontal stroke is understood as a transformed remnant of the three-dot form. This reading is supported by the character

chong in the

Preface to Sage Teachings, where a similar horizontal stroke appears. At the beginning of his postscript to the

Preface, L├╝ Haihuan Õæ鵥ĘÕ»░ (1843ŌĆō1927) remarks: ŌĆ£In this edition of the

Preface, the character

chong contains three faint small dots below the mountain radical.ŌĆØ

15 Contrary to his comment, the actual character form clearly exhibits a single short horizontal stroke, and it suggests that the three dots might have undergo transformation into other configurations, though at times stylized or obscured. In this vein, the horizontal stroke in the Shenlong edition is also construed as a vestige of the original three-dot form.

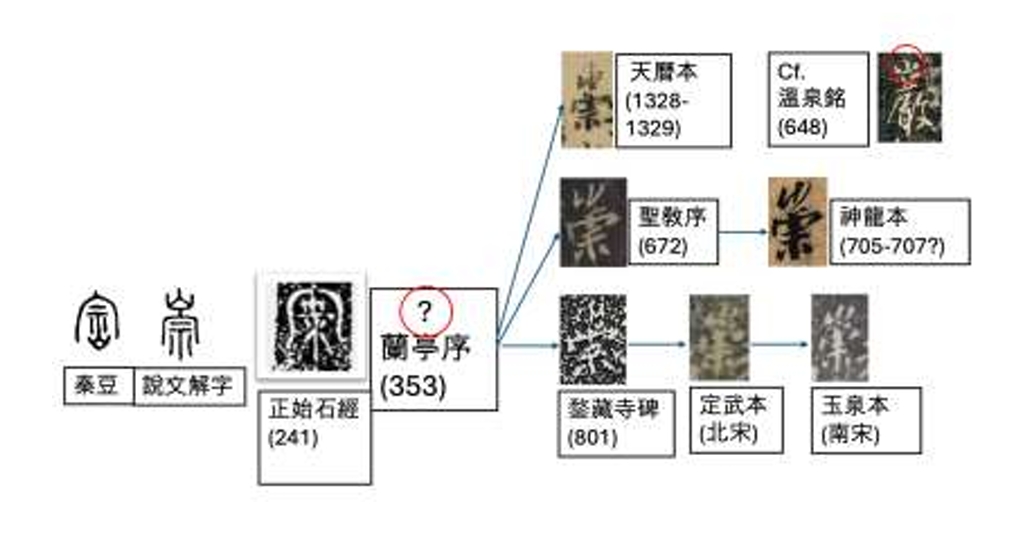

Most interesting is the third lineage of three-dot form in the Dingwu edition and the Mujangsa Stele. Weng Fanggang believed that the Dingwu edition is more faithful to the original than the Yuquan edition, based on the three dots as a point of reference. If his conjecture is correct, a new question arises: on what basis did Wang Xizhi add the three dots to the character? The chart above may provide a clue for the origin of the three dots.

Arguably, the earliest form of the three dots traces back to the character

chong on a Qin-dynasty bronze vessel ń¦”Ķ▒å, in which a mountain-like form appears in the lower part of the character. In the

Shuowen jiezi Ķ¬¬µ¢ćĶ¦ŻÕŁŚ, this component was repositioned to the upper part of the character. It seems to have transformed into three dots in the

Stone Classics of the Zhengshi Era µŁŻÕ¦ŗń¤│ńČō (240-248), also known as the

Three-Script Stone Classics õĖēķ½öń¤│ńČō for its inclusion of ancient script ÕÅżµ¢ć, clerical script ķÜĖµøĖ, and small seal script Õ░Åń»å. The three dots are inscribed inside the roof radical (

mian Õ«Ć) of the ancient script

chong. This placement differs from later editions in which the dots appear beneath the mountain radical (

shan Õ▒▒), but their presence remains discernable. Given that only about a century separates the

Stone Classics (241) and WangŌĆÖs

Preface (353), it is plausible that Wang may have drawn upon the three-dot form found in the

Stone Classics. Later, Weng FanggangŌĆÖs view was underpinned by Liu Xihai ÕŖēÕ¢£µĄĘ (1794-1852) and Ye Zhixian ĶæēÕ┐ŚĶ®Ą (1779-1862). Furthermore, Ye Changchi ĶæēµśīńåŠ (1849-1916) associated Korean calligraphic practice as a result of Tang militarism.

16 Unsurprisingly, WengŌĆÖs view was widespread among contemporary Korean scholars, such as Yi Sangch┼Åk µØÄÕ░ÖĶ┐¬ (1804-1865) and Yi Yuw┼Ån µØÄĶŻĢÕģā (1814-1888). It was a somewhat expected situation, given WengŌĆÖs prominent status in Chos┼Ån. Exceptionally, Weng Shukun and Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi did not concede to the mainstream view.

Weng Shukun was the sixth and youngest son of Weng Fanggang. He collected rubbings of Korean steles more extensively than his father through his connections with Korean scholars. Alongside the rubbings, the Korean scholars also provided relevant historical information, such as the authorŌĆÖs name and the year of inscription. This kind of information was common knowledge for Korean scholars but was needed for Chinese scholars. In return, Weng imparted epigraphical methodologies to Korean colleagues. For example, rubbings should include

piaek ńóæķĪŹ ŌĆ£the heading of the steleŌĆØ and the

chanŌĆÖgy┼Ål µ«śń╝║ ŌĆ£worn-out parts of the inscribed textsŌĆØ as well as the legible characters. Weng also emphasized the material form and format of steles, such as the number of characters in each line, the total number of lines of the entire inscription, and the margins around the inscription.

17 Subsequently, Korean scholars began to examine not only content but also materiality of steles. Weng ShukunŌĆÖs Korean colleagues included Hong Hy┼Ånju µ┤¬ķĪ»Õæ© (1793-1865), Sim Sanggyu µ▓łĶ▒ĪÕźÄ (1766-1838), and Sin Wi ńö│ńĘ» (1769-1845), while Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi remained his favorite friend. Weng and Kim happened to be of the same age. One token of their close friendship is WengŌĆÖs epithet, Xing-Qiu µś¤ń¦ŗ (K: S┼Ång-ChŌĆÖu); the two characters form a fusion of WengŌĆÖs courtesy name, Xingyuan µś¤ÕĤ, and KimŌĆÖs style name, ChŌĆÖusa ń¦ŗÕÅ▓.

In his

Su-Mi zhai Lanting kao, as previously discussed, Weng Fanggang argued that the

Mujangsa Stele was a case of collation, but Weng Shukun did not accept this theory. Instead, he upheld the traditional view that Kim Yukchin was both the author and the calligrapher of the stele. He appended a handwritten note to his fatherŌĆÖs book,

18 as if to correct his fatherŌĆÖs conclusion.

Weng Shukun expressed his view again in his

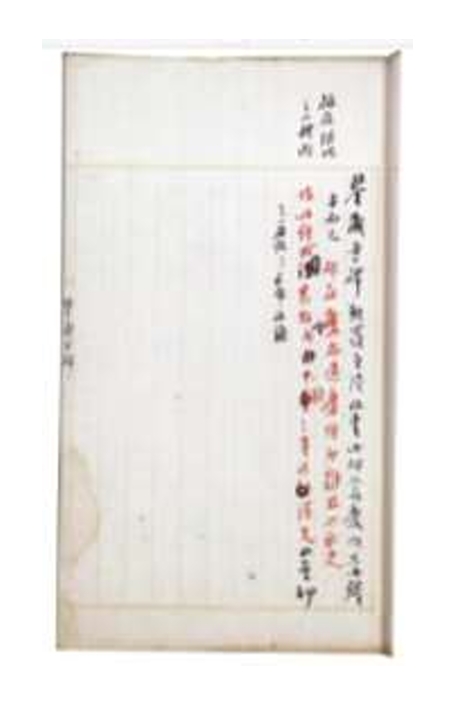

Haidong jinshi lingji µĄĘµØ▒ķćæń¤│ķøČĶ©ś (Miscellaneous Notes on Korean Epigraphy).

19 The entry on the

Mujangsa Stele reads (see

Figure 6).

20

The Mujangsa Stele was the brushwork of Kim Yukchin of Silla. This is also located in Ky┼Ångju, though only a fragmentary edition survives. The stele stands in Ky┼Ångju, which is none other than ancient Kyerim. Chusa [Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi]

ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæ µ¢░ńŠģķćæķÖĖńÅŹµøĖ. µŁżńóæõ║”Õ£©µģČÕĘ×, ÕŬµŁżµ«śµ£¼ĶĆīÕĘ▓. ńóæÕ£©µģČÕ░ÖķüōµģČÕĘ×, ÕŹĮķĘäµ×Śõ╣¤. ń¦ŗÕÅ▓

This style of rubbing technique is excellent. Did they perhaps use Chinese ink to achieve such luster? I request that you make rubbings again, and that send me around three to five copies.

µā¤ń©«µŗōµ│ĢńöÜÕźĮ, µŁżµł¢ńö©õĖŁÕ£ŗõ╣ŗÕó©, õ╣āÕŠŚÕģēÕ”éµś»ĶĆČ? õ╣×ÕåŹ’©éõĖēõ║öń┤Öńł▓ń”▒.

[Head Commentary] Postscript is in the Suoji, a single book.

21

[ķĀŁĶ©╗] ĶĘŗÕ£©ńæŻĶ©śõ╣ŗõĖĆÕåŖÕģ¦.

Weng Shukun, with the assistance of Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi, attributed the Mujangsa Stele to the calligraphy of Kim Yukchin. He also appended a note requesting additional copies of the rubbing from Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi for further research. However, by that time, the stele had disappeared, making it impossible to produce a new rubbing.

In addition, Weng Shukun produced a stele illustration (

pido ńóæÕ£¢) based on the inscription fragments, and noted before the first line of the text, ŌĆ£It seems there was an additional line hereŌĆØ µŁżĶÖĢõ╝╝Õ░Öµ£ēõĖĆĶĪī.

22 Amid this ongoing exchange of views, Weng Shukun suddenly passed away. Upon hearing the news, Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi was deeply grieved and, in memory of his late friend, traveled to Ky┼Ångju.

The site of Mujangsa Temple was overgrown by bushes when Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi reached on the twenty-ninth day of the fourth month of 1817. Kim searched through the bushes and found the right-side part of the stele, the major fragment that Hong Yangho first found. Kim explored further and discovered another fragment, this time the left-side of the stele, which surprisingly contained the line Weng had hypothesized. KimŌĆÖs discovery proved WengŌĆÖs speculation. Kim moved the two fragments to a safe place behind the temple. Then he inscribed his own remarks on the lateral side of each stone fragment. The one written on the major one is more detailed and comprehensive.

23

This stele was formerly known only by a single fragment. During my exhaustive search, I discovered an additional broken piece amidst the overgrowth. I was overwhelmed with joy and shouted aloud in amazement. I placed the two stones together, like linked pearls, and moved them to the rear corridor of the temple to protect them from the elements. The quality of the calligraphy on this stone surpasses even that of the Paengwŏl Stele. The character sung with three dots, as in the Orchid Pavilion, is fully preserved only on this stone. Master Weng Tanxi [Fanggang] used this stele as evidence [for his theory of collation]. Among Korean inscriptions praised in China, none has been held in higher esteem than this stele. I caressed the broken stele multiple times and regretted that Xingyuan [Shukun] could not view the lower portion [that he mentioned.]

Inscribed by Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi on the twenty-ninth day of the fourth month in the year of Ch┼ÅngchŌĆÖuk (1817)

µŁżńóæĶłŖÕŬõĖƵ«ĄĶĆīÕĘ▓, õĮÖõŠåµŁżń¬«µÉ£, ÕÅłÕŠŚµ¢Ęń¤│õĖƵ«Ąµ¢╝ĶŹÆĶÄĮõĖŁ, õĖŹÕŗØķ®ÜÕ¢£ńĄČÕŽõ╣¤. õ╗ŹõĮ┐Õģ®ń¤│, ÕÉłÕŻüńÅĀĶü», ń¦╗ńĮ«Õ»║õ╣ŗÕŠīÕ╗Ŗ, õ┐ŠÕģŹķó©ķø©. µŁżń¤│µøĖÕōü, ńĢČÕ£©ńÖĮµ£łńóæõĖŖ. ’ż¤õ║Łõ╣ŗÕ┤ćÕŁŚõĖēķ╗×, Õö»µŁżń¤│ńē╣Õģ©. ń┐üĶ”āµ║¬Õģłńö¤õ╗źµŁżńóæńł▓ĶŁē. µØ▒µ¢╣µ¢ćńŹ╗õ╣ŗĶ”ŗń©▒µ¢╝õĖŁÕ£ŗ, ńäĪÕ”éµŁżńóæ. õĮֵ段ī▓õĖēÕŠ®, µ£ēµä¤µ¢╝µś¤ÕĤõ╣ŗńäĪõ╗źĶ”ŗõĖŗµ«Ąõ╣¤. õĖüõĖæÕøøµ£łÕŹäõ╣صŚź, ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£ķĪīĶŁś.

Kim first explains how he discovered the two broken parts of the stele and proceeds to evaluate their calligraphic merit in comparison with the Paekw┼Åls┼Åun Pagoda Stele ńÖĮµ£łµĀ¢ķø▓ÕĪöńóæ, erected in 954 in memory of the Buddhist master Nanggong ’ż®ń®║ (832ŌĆō916). That inscription was engraved based on the calligraphy of Kim Saeng, the renowned Korean calligrapher introduced at the beginning of this article. Yet, in KimŌĆÖs assessment, the Mujangsa Stele still surpasses the Pagoda Stele in artistic valueŌĆönot only because it predates it, but also because it preserves authentic traces of Wang XizhiŌĆÖs brushwork, such as the distinctive three-dot form of the character sung Õ┤ć, a feature that had drawn the attention of Weng Fanggang. Notably, though, Kim does not refer to WengŌĆÖs theory of ŌĆ£collating characters.ŌĆØ This is another indirect evidence that Kim did not support his masterŌĆÖs view.

After about fifteen-day trip to Ky┼Ångju, Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi returned to Seoul and engaged more earnestly in epigraphic studies in collaboration with fellow scholars. In the course of this research, he once again expressed his views on the

Mujangsa Stele in a letter to Kim Ky┼Ångy┼Ån ķćæµĢ¼µĘĄ (1778ŌĆō1820). Although the precise date of the letter is not recorded, it is presumed to have been written around the autumn of 1817, a period when the two men were deeply immersed in the study of epigraphy.

24

The Mujangsa Stele is indeed written in the calligraphic style of the Hongboksa Stele, but it is not a collated inscription like the Ingaksa Stele. Kim Yukchin was a figure of the late Silla period. The date of the steleŌĆÖs erection cannot be verified at present.

ķŹ¬ĶŚÅńóæµ×£µś»Õ╝śń”ÅÕŁŚķ½ö, ķØ×ķøåÕŁŚÕ”éķ║¤Ķ¦Æńóæń¤Ż. ķćæķÖĖńÅŹµś»µ¢░ńŠģµ£½Ķæēõ╣ŗõ║║, ĶĆīńóæõ╣ŗÕ╣┤õ╗Ż, õ╗ŖõĖŹÕÅ»ĶĆāń¤Ż.

KimŌĆÖs remarks are terse and ambiguously phrased, making them difficult to understand with precision. He initially affirms Weng FanggangŌĆÖs view that the inscription was rendered in the style of the

Hongfusi Stele that engraved the Preface to the Sage Teachings Ķü¢µĢÖÕ║Å. What follows, however, is a problematic passage that lends itself to two possible interpretations. One possibility is that the stele is not a collated work, unlike the

Ingaksa Stele.

25 Alternatively, the stele is a collated work, akin to the

Hongfusi Stele, but of a different kind than the

Ingaksa Stele. In my view, Kim likely intended the first interpretation, especially given his remarks in the aforementioned book Miscellaneous Notes by Weng Shukun. In the next, Kim refers to Kim Yukchin, seemingly suggesting that he was the actual inscriber, though he does not elaborate on this point. It is possible that Kim was reluctant to openly contradict the position of his mentor, Weng Fanggang.

Debates Among Modern Scholars

To this day, scholarly consensus has not been reached regarding the calligraphic style of the

Mujangsa Stele.

26 Lee Jong-moon is the earliest scholar who suggested a Korean calligrapher.

27 Yi points out that about one-quarter of the characters on the stele are not found in any extant works by Wang Xizhi. Even some characters are too complicated to assemble parts from WangŌĆÖs corpus. Yet, they still achieve the uniformity in the size and stroke breath of the characters, the lively rhythm and continuity of brush energy, and the overall harmonious composition. Those features attest that the inscription of the stele could not be made through assembling pre-existing characters.

Choi Young-sung supported YiŌĆÖs position and proposed a new theory that the calligrapher was a monk from Hwangnyongsa Temple. He deciphered the character

sa Õ»║ after

Hwangryong ńÜćķŠŹ near the lower end of the first column on the stele, and suggested that it would have been followed by the name of the temple monk who wrote the inscription.

28

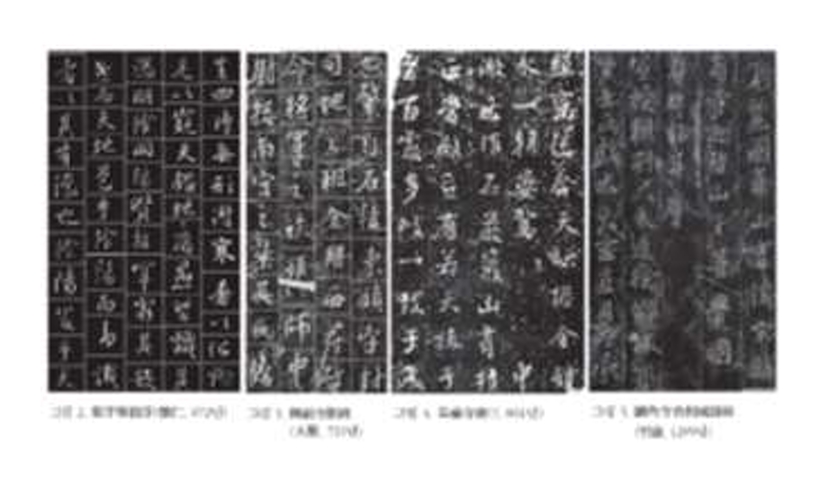

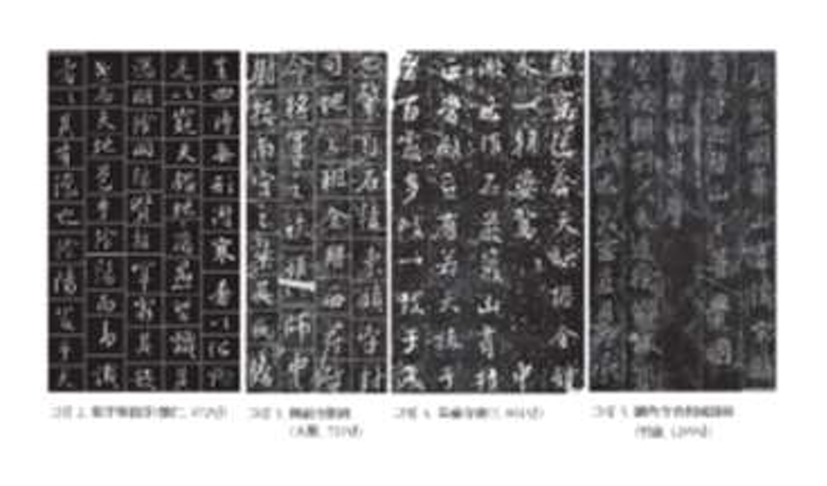

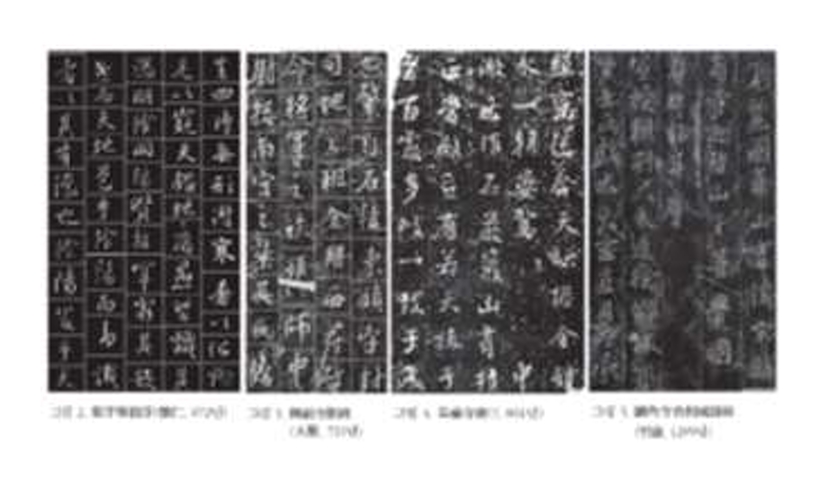

Building on the arguments of Lee Jong-moon and Choi Young-sung, Lee Eun-Hyuk further developed the debate by organizing his analysis around three aspects: character size, historical context, and calligraphic style. His main arguments can be summarized as follows. Lee first draws attention to the size of the characters on the

Mujangsa Stele in comparison to three other steles made through the collation method (see

Figure 7).

Lee Eun-Hyuk effectively illustrated the irregular distribution of character sizes in the two Chinese steles by overlaying horizontal and vertical lines on the inscriptions. The Hongfusi Stele, or Stele of the Preface to Sage Teachings, has slightly narrower spacing between characters than the Broken Stele of Xingfusi. Yet in both cases, variation in character size is clearly noticeable. In contrast, the Mujangsa Stele exhibits a high degree of formal consistency. Vertical guidelines were drawn on the stone surface to ensure even spacing between columns, and then characters were inscribed at regular intervals along these lines. The spacing between columns is orderly, and the characters are rendered in a uniform size throughout, intending a deliberate structural cohesion. Based on these observations, Yi concludes that the Mujangsa Stele was executed by a single calligrapher.

Yi further states that the Ingaksa Stele displays an uneven format, resembling the layout of the two Chinese steles. However, from my own observation, the Ingaksa Stele is still relatively consistent in character size and spacing, closely approximating the organization seen in the Mujangsa Stele. Thus, it seems reductive to interpret varying sizes solely through the lens of the collation process. A more plausible explanation would be regional stylistic conventions. Whereas Chinese steles have texts in open space, Korean ones employed vertical guidelines. The two different formats suggest disparate underlying aesthetics pertaining to spatial organization.

Meanwhile, one interpretative issue arises regarding character size. Lee Eun-Hyuk initially attributes the irregularity in character size to the inherent limitations of collation process. Because characters are collected from a variety of sources, their sizes naturally vary. Later, however, he interprets the same phenomenon as an embodiment of the so-called

canchaimei ÕÅāÕĘ«ńŠÄ (K.

chŌĆÖamchŌĆÖimi), a key aesthetic principle in Chinese calligraphy that esteems unevenness, asymmetry, and variation.

29 In other words, it remains unclear whether the variation in character size is regarded as a technical limitation resulting from the compilation process or as a deliberate aesthetic choice. If the former is the case, it rightly points to a structural weakness inherent in collated characters. But if it is the latter, it bears no direct relevance to the issue of ŌĆ£collation theory.ŌĆØ

The second point of discussion pertains to the historical circumstance regarding the construction of the Mujangsa Stele. As evidenced by the fact that the Stele of the Preface to Sage Teachings took twenty-five years to complete, the process of collating characters requires extensive source materials and a great deal of time. In the case of the Mujangsa Stele, however, it was created as part of a Buddhist ritual intended to pray for the repose of the deceased kingŌĆÖs soul. Given the urgency of such a task, the time frame must have been tightŌĆöindeed, the stele was completed within a year of the kingŌĆÖs passing. Under such time constraints, making new characters based on collation process is highly impractical.

The second argument is overall reasonable, but it still warrants further elaboration. LeeŌĆÖs argument relies solely on the example of the

Preface to Sage Teachings, making the comparison overly dependent on a single precedent. Incorporating a broader range of examples would strengthen his argument.

30 The

Preface to Sage Teachings was the first successfully executed collated stele, and thus its production likely required an exceptionally long period due to the novelty and complexity of the process. By contrast, when the

Mujangsa Stele was erected, the

Preface to Sage Teachings and other Chinese sources were available, potentially streamlining the production process and significantly reducing the time required. Moreover, the

Preface to Sage Teachings consists of 1,904 characters, considerably more than the estimated 1,400 characters of

the Mujangsa Stele.

Lastly and most importantly, Lee Eun-Hyuk classified all 431 deciphered characters from the

Mujangsa Stele into three categories based on their degree of resemblance to Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy.

31 The results of his classification are as follows:

(1) Characters identical to those in Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy: 156 characters

(2) Characters that appear in WangŌĆÖs corpus but differ in form: 161 characters

(3) Characters not found in WangŌĆÖs calligraphy: 114 characters

(4) Others: Characters that are undecipherable or require further clarification

LeeŌĆÖs study is grounded in direct visual comparison with Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy, and his systematic analysis provides a solid foundation for addressing the issue of collated characters. Categories (2) and (3)ŌĆöthat is, characters whose forms differ from those in Wang XizhiŌĆÖs works or are not found in his calligraphyŌĆötogether comprise approximately 270 characters, nearly twice the number of those matching WangŌĆÖs calligraphy in Category (1). Although Category Two may vary, depending on the viewerŌĆÖs judgment, the high number of characters either absent from or significantly different in WangŌĆÖs extant works supports the argument that the Mujangsa Stele is not a product of assembling characters from preexisting works. Taken as a whole, Lee Eun-HyukŌĆÖs reasoning and progression toward his conclusion are logically sound and convincing although the two minor issuesŌĆöcharacter size and historical circumstanceŌĆöneed further consideration.

Among scholars in support of a single inscriber, opinions remain divided regarding the identity of the calligrapher. While Choi Young-sung and Lee Eun-Hyuk suggest a Hwangnyongsa monk or a third party, Lee Jong-moon continues to regard Kim Yukchin as the calligrapher, based on textual evidence.

32 Since this study focuses primarily on the broader debate between the single-inscriber and collation theories, internal disagreements within the former camp will not be addressed in detail here.

Now let us turn to the arguments of scholars advocating the collation theory. In this group of scholars,

33 Kim Ŭnghyŏn is the first scholar to advance a scholarly argument of the collation theory. He explained that even collated inscriptions can reflect the individuality of the person assembling the characters.

34 Building upon his discussion, Jung Hyun-sook developed the theory further.

35 The script style of the

Mujangsa Stele differs from that of Wang Xizhi in the Chinese sources, but such a level of difference is not significant to assert a single inscriber on the ground of the process of collating characters. The process first involves locating the relevant characters, which are then manually copied one by one; as such, the final form may vary depending on the collatorŌĆÖs skill and stylistic choices. In her view, therefore, the scriptural differences between the

Mujangsa Stele and the works of Wang Xizhi do not necessarily support the theory of a single inscriber.

Moreover, Jung Hyun-sook draws attention to the formal aspects of the inscription. While she accepts Choi Young-sungŌĆÖs claim that the name of a monk was engraved at the bottom of the first line of the stele, she argues that this monk was not the inscriber but rather the monk in charge of collation. As evidence, she pointed to the fact that in both the

Preface to Sage Teachings and the

Broken Stele of Xingfusi Temple, the name of the collating monk follows the temple name at the beginning of the inscription.

36

The format of the Preface to Sage Teachings is particularly noteworthy; a large blank space is between the phrase ŌĆ£Composed by Emperor TaizongŌĆØ Õż¬Õ«Śµ¢ćńÜćÕĖØĶŻĮ and ŌĆ£Hongfusi TempleŌĆØ Õ╝śń”ÅÕ»║. This format aligns with that of the Mujangsa Stele, where ŌĆ£Taenaema Minister Kim Yukjin, in obedience to the requestŌĆØ Õż¦Õźłķ║╗ĶćŻķćæķÖĖńÅŹÕźēµĢÄ is followed by a blank of more than four characters before ŌĆ£HwangnyongsaŌĆØ ńÜćķŠŹÕ»║ is written. Based on such a similar format, Jung infers that the full inscription of the Mujangsa Stele likely reads: ŌĆ£Hwangnyongsa [ŌĆśa name of monkŌĆÖ collated writings of General Wang Xizhi of Jin]ŌĆØ ńÜćķŠŹÕ»║ [Ō¢ĪŌ¢Ī ķøåµÖēÕÅ│Õ░ćĶ╗ŹńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗµøĖ].

Jung Hyun-sook further notes that when a monk serves as an inscriber, there is no precedent for his name to appear at the beginning of an inscription. By contrast, in the case of collated works, the collatorŌĆÖs name is typically placed at the beginning, as seen in the two aforementioned Chinese steles and in SillaŌĆÖs

Master Honggak Stele (886). On this basis, Jung concludes that the Hwangnyongsa monk in question should be regarded not as an inscriber, but as a collating monk. On the whole, Jung articulates a well-reasoned argument, grounding her analysis in the concept of collation and formal comparisons with other compiled steles. However, we need to re-consider her claim that the name of the collating monk appears at the beginning of the inscription. One counter example is the

Ingaksa Stele, whose inscription ends with:

Disciple-monk Jukh┼Å, having received the imperial edict, collated the characters of General Wang Xizhi of Jin. Disciple ChŌĆÖ┼Ångbun, Abbot of Palace Temple and Ingaksa Temple, TŌĆÖongŌĆÖo Chinj┼Ång Grand S┼Ån Master erected the stele.

ķ¢Ćõ║║µ▓Öķ¢Ćń½╣ĶÖøÕźē ÕŗģķøåµÖēÕÅ│Õ░ćĶ╗ŹńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗµøĖ. ķ¢Ćõ║║Õģ¦ķĪśÕĀéÕģ╝õĮŵīüķĆÜÕź¦ń£×ķØ£Õż¬ń”¬ÕĖ½µĘĖńÄóń½ŗń¤│.

As shown above, the name of the collating monk appears at the very end of the inscription. It suggests that a more comprehensive investigation is necessary for validating Ch┼ÅngŌĆÖs argument.

Concluding Remarks

I have reviewed modern scholarly works with a main focus on Lee Eun-Hyuk and Jung Hyun-sook, followed by my own view. First, Lee and Jung stand at the opposite sides, but they have shared views at times. Both scholars noted that the script of the Mujangsa Stele most closely resembles that of the Hongfusi Stele, i.e., the Stele of the Preface to Sage Teachings. This observation aligns well with the historical context. At the time the Mujangsa Stele was erected, the Preface to the Orchid Gathering was already an extremely rare text and difficult to obtain, while the Broken Stele of Xingfusi had not yet been discovered. Thus, the Hongfusi Stele would have been the most accessible and useful source for reproducing the calligraphic style of Wang Xizhi.

As for the script style of the Mujangsa Stele, both Lee and Jung exhibit some points of convergence in their analysis, but they differ in interpretation and emphasis. Attention to these differences reveals the core of the debate and may offer insights toward its resolution. Lee remarks that the strokes are uniform and sharp. Similarly, Jung observes that, compared to the two Tang-dynasty steles, the strokes are thinner and exhibit characteristics of regular script, producing a ŌĆ£lean and rigidŌĆØ (sugy┼Ång ńś”ńĪ¼) feature. As such, their descriptive accounts largely coincide, but their interpretations diverge. Lee argues that the evenness of the brushwork and the regular spacing between characters point to a single calligrapherŌĆÖs hand. In contrast, Jung maintains that since collation involves a manual process of copying at the end, such a consistent script style happens naturally.

Now I would like to offer my own view. While both Lee and Jung make valid points on their own, each appears to have limitations when it comes to evaluating the script of the

Mujangsa Stele in its entirety. Lee notes that 156 out of the 431 deciphered characters in the stele match Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy. Although this number does not account for half, it still represents a significant portion. These characters were likely compiled based on extant materials such as the

Preface to Sage Teachings. Jung Hyun-sook, on the other hand, argues that for characters not found in WangŌĆÖs corpus, the collating monk would have had no choice but to write them in the style of Wang Xizhi.

37 This statement effectively acknowledges the role of the inscriber to a certain degree. Given that a substantial number of characters in the stele are not attested in WangŌĆÖs model calligraphy, they cannot be dismissed as negligible.

Considering that both theories have some limitations, it seems most reasonable to adopt a hybrid view: characters traceable to WangŌĆÖs models were collated, while those absent were written directly by the inscriber. Song Mingxin previously proposed such a view that both collation and freehand copy are evident in the inscription. He concluded that the script of the

Mujangsa Stele represents a creative adaptation of Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy.

38

The most contentious issue concerns a group of Chinese characters that appear in Wang XizhiŌĆÖs calligraphy but take different forms in the Mujangsa Stele. Lee identifies a total of 161 such characters and, based on this observation, concludes that the inscription reflects one individualŌĆÖs creative handwriting. In contrast, Jung attributes the variations to the collating monkŌĆÖs level of skill and personal style. The two opposite interpretations may involve subjective judgment, and the issue exceeds the present authorŌĆÖs capacity for definitive resolution. Thus, rather than pursue the issue further here, I leave it open to future research.

Lastly, let us return to the varied forms of the character

sung Õ┤ć. Thus far, scholarly discussions have focused on the presence of the three dots. However, equal attention should be given to the lower component Õ«Ś (K.

chong, Ch.

zong). In the

Mujangsa Stele, this component appears in its standard form, whereas in the Dingwu editions, the thick central stroke of the character pierces straight through the entire

zong component, as Weng Fanggang mentioned (see the chart above).

39 In other words, the Korean inscriber adopted the three-dot form but did not replicate the penetrating stroke, which is also characteristic of the Dingwu editions. This divergence highlights the creative agency of the Korean calligrapher, whose approach reflects a selective and interpretive engagement with the model rather than mechanical reproduction.

Notes

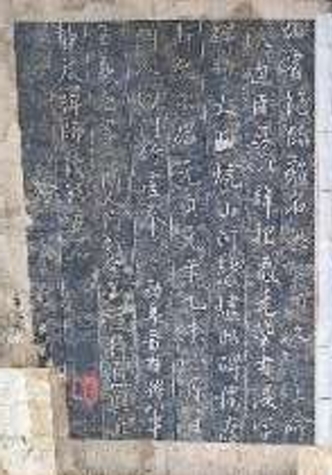

Figure 1.Details of rubbings of the Mujangsa Stele. Dimensions unknown. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

Figure 2.Beginning section of the Dingwu edition. Handscroll, dimensions unknown. National Palace Museum in Taipei. Image number: K2D000001N000000000PAC.

Figure 3.Beginning section of the Dingwu edition. Handscroll, Height 24 cm, Width 9.5 cm. Image number: Õ«ŗµŗōիܵŁ”Õģ░õ║ŁÕ║Å µ¢░00135367. The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Figure 4.Beginning section of the Yuquan edition. Dimensions: Height 25.2 cm, Width 11.1 cm, Kyoto National Museum, Japan. After ┼ī Kishi to Ranteisho ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗŃü©ĶśŁõ║ŁÕ║Å, 27.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Haidong jinshi lingji µĄĘµØ▒ķćæń¤│ķøČĶ©ś, Entry. Mujangsa Stele

Figure 7.From left to right: (a) Huairen, Hongfusi Stele (672), (b) Daya, Broken Stele of Xingfusi (721), (c) Kim Yukjin (arguably), Mujangsa Stele (801), and (d) Chukh┼Å, Ingaksa Stele (1295). From Lee Eun-Hyuk, ŌĆ£Mujangsa pi wa Wang H┼Łiji chŌĆÖe ┼Łi taebi kochŌĆÖal,ŌĆØ 186.

Figure 8.Rubbing of the Ingaksa Stele Inscription, 1295. Accordion-fold Album (12 Folds), 39.2 ├Ś 27 cm. Jangseogak no. B14B 29

Chart: The Graphical Development and Variants of the Character Chong

- Choi, Young-sung. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Silla Mujangsa pi ┼Łi s┼Åja y┼ÅnguŌĆØ µ¢░ńŠģ ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæņØś µøĖĶĆģ ńĪÅń®Č [A Study on the Calligrapher of the Mujangsa Stele of Silla)].ŌĆØ Sillasa hakpo 20 (2010): 179-218.

- De Laurentis, Pietro. Protecting the Dharma through Calligraphy in Tang China: A Study of the Ji Wang Shengjiao Xu: The Preface to the Buddhist Scriptures Engraved on Stone in Wang XizhiŌĆÖs Collated Characters. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

- Fujitsuka Chikashi ĶŚżÕĪÜķä░. Shincho╠ä bunka to╠äden no kenkyu╠ä: Kakai Do╠äko╠ä gakudan to Richo╠ä no Kin Gendo╠ä µĖģµ£Øµ¢ćÕī¢µØ▒Õé│Ńü«ńĀöń®Č: ÕśēµģČŃā╗ķüōÕģēÕŁĖÕŻćŃü©µØĵ£ØŃü«ķćæķś«ÕĀé [A Study of the Culture of Qing and its Reception in the East: Schools of Jiaqing and Daoguang Reigns and Kim Wandang of Chos┼Ån]. To╠äkyo╠ä: Kokusho kanko╠äkai ÕøĮµøĖÕłŗĶĪīõ╝Ü, 1975.

- Hong Yangho µ┤¬Ķē»µĄ® (1724-1802). Igye chip ĶĆ│µ║¬ķøå [Collected Works of Hong Yangho]. HanŌĆÖguk munjip chŌĆÖonggan ķ¤ōÕ£ŗµ¢ćķøåÕÅóÕłŖ. Vol. 241. Seoul: Ky┼Ångin munhwasa, 2000.

- Iry┼Ån õĖĆńäČ (1206-1289). Samguk yusa õĖēÕ£ŗķü║õ║ŗ [Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms], Kyujanggak edition (1512).

- Jung Hyun-sook. TŌĆÖongil Silla ┼Łi s┼Åye ĒåĄņØ╝ņŗĀļØ╝ņØś ņä£ņśł [The Calligraphy of Unified Silla]. Seoul: Daunsaem, 2022.

- Jung, Hyun-sook. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£HanŌĆÖguk s┼Åyesa es┼Å Wang Huiji chipchabi ┼Łi ch'urhy┼Ån gwa ch┼ÅnŌĆÖgaeŌĆØ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ņä£ņśłņé¼ņŚÉņä£ ņÖĢĒؼņ¦Ć ņ¦æņ×Éļ╣äņØś ņČ£ĒśäĻ│╝ ņĀäĻ░£ [The Appearance and Development of the Stelae Written in Wang XizhiŌĆÖs Characters in the History of Korean Calligraphy].ŌĆØ S┼Åyehak y┼ÅnŌĆÖgu 44 (2024): 5-36.

- Kim Pusik ķćæÕ»īĶ╗Š (1075-1151), comp. Samguk sagi õĖēÕ£ŗÕÅ▓Ķ©ś [History of Three States]. Ch┼Ångd┼Åk edition (1512).

- Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£ (1786-1856). Wandang chip ķś«ÕĀéķøå [Collected Works of Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi]. HanŌĆÖguk munjip chŌĆÖonggan ķ¤ōÕ£ŗµ¢ćķøåÕÅóÕłŖ. Vol. 283-4. Seoul: Ky┼Ångin munhwasa, 1988.

- Kim ┼¼nghy┼Ån. S┼Å y┼Å ki in µøĖÕ”éÕģČõ║║ [Writing Mirrors the Man]. Seoul: Tongbang y┼Åns┼Åhoe, 1995.

- Ledderose, Lothar. Mi Fu and the Classical Tradition of Chinese Calligraphy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Lee, Eun-Hyuk. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Mujangsa pi wa Wang HŪöiji chŌĆÖe Ūöi taebi kochŌĆÖalŌĆØ ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæņÖĆ ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗķ½öņØś Õ░Źµ»öĶĆāÕ»¤ [A Comparative Study of the Mujangsa Stele and Wang XizhiŌĆÖs Style].ŌĆØ Hanguk chŪÆtŌĆÖong munhwa yŪÆnŌĆÖgu 12 (2013): 171-212.

- Lee, Jong-moon. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Mujangsabi r┼Łl ss┼Łn s┼Åyega e kwanhan han koch'alŌĆØ ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæļź╝ ņō┤ µøĖĶŚØÕ«ČņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ĒĢ£ ĶĆāÕ»¤ [A Study on the Calligrapher of the Mujangsa Stele].ŌĆØ Nammyeonghak y┼ÅnŌĆÖgu 13 (2002): 223-54.

- Lee, Jong-moon. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Mujangsabi r┼Łl ss┼Łn s┼Åyega e taehan chae k┼ÅmtŌĆÖoŌĆØ ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæļź╝ ņō┤ µøĖĶŚØÕ«ČņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ÕåŹµ¬óĶ©Ä [A Reexamination of the Calligrapher of the Mujangsa Stele].ŌĆØ Taedong Hanmunhak 41 (2014): 271-302.

- Little, Stephen and Virginia Moon, eds. Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing. California: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2019.

- Liu Xu ÕŖēµś½ (888-947), comp. Jiu Tangshu ĶłŖÕöɵøĖ [Old History of Tang]. Beijing, Zhonghua shuju, 1975.

- Nishikawa Yasushi Ķź┐ÕĘØÕ»¦. ŌĆ£Cho╠ä Kinkai do hon ni tsuiteŌĆØ Õ╝ĄķćæńĢīÕź┤µ£¼Ńü½ŃüżŃüäŃü” [Regarding the Zhang Jinjie edition]. In Sho╠äwa Rantei kinen ten µśŁÕÆīĶśŁõ║ŁĶ©śÕ┐ĄÕ▒Ģ [Sho╠äwa Exhibition Catalogue of Rantei]. To╠äkyo╠ä: Nigensha, 1973, 227-238.

- Pak Chulsang [Pak ChŌĆÖ┼Ålsang]. Na n┼Łn yetk┼Åt i choa ttaeron kkaejin pittol ┼Łl ch'aja tany┼Åtta: Ch'usa Kim Ch┼Ång-h┼Łi ┼Łi k┼Łms┼Åkhak ļéśļŖö ņśøĻ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗņĢä ļĢīļĪĀ Ļ╣©ņ¦ä ļ╣ŚļÅīņØä ņ░ŠņĢäļŗżļģöļŗż: ń¦ŗÕÅ▓ ķćæµŁŻÕ¢£ņØś ’żŖń¤│ÕŁĖ [I am Fond of the Ancient, And So I Searched for Broken Steles: Epigraphy of ChŌĆÖusa Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi]. Seoul: N┼Åm┼Å puks┼Ł, 2015.

- Park, Hyun-Kyu. ŌĆ£[Pak Hy┼ÅnŌĆÖgyu]. ŌĆ£Haidong jinshi lingji ┼Łi s┼Åja wa shilsang,ŌĆØ µĄĘµØ▒ķćæń¤│ķøČĶ©śņØś ĶæŚĶĆģņÖĆ Õ»”ńŗĆ [The Authorship and Nature of Haidong jinshi lingji].ŌĆØ Taedong Hanmunhak 35 (2011): 385-413.

- Shin, Jeongsoo. ŌĆ£Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi and His Epigraphic Studies: Two Silla Steles and Their Rubbings.ŌĆØ Journal of Korean Studies 27, no.2 Octoberņøö (2022): 199-223.

- Song Mingxin Õ«ŗµśÄõ┐Ī. ŌĆ£Moucangsi bei de shuxie zhe yu shuti fenxiŌĆØ ķŹ¬ĶŚÅÕ»║ńóæńÜäµøĖÕ»½ĶĆģĶłćµøĖķ½öÕłåµ×ÉŌĆØ [An Analysis of the Inscriber and Script Style of the Mujangsa Stele]. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Mujangsa Stele of Silla, 2010, pp. 227-231.

- Taito╠ä Kuritsu. ┼ī Kishi to Ranteisho ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗŃü©ĶśŁõ║ŁÕ║Å. Shodo╠ä HakubutsukanÕÅ░µØ▒Õī║ń½ŗµøĖķüōÕŹÜńē®ķż© Tokyo: Taito╠äku gakujutsu bunka zaidan ÕÅ░µØ▒Õī║ÕŁĖĶĪōµ¢ćÕī¢Ķ▓ĪÕ£ś, 2023.

- Weng Fanggang ń┐üµ¢╣ńČ▒. Su-Mi zhai Lanting kao Ķśćń▒│ķĮŗĶśŁõ║ŁĶĆā [Investigation on the Orchid Pavilion at the Studio of Su-Mi]. In Wu Chongyao õ╝ŹÕ┤ćµø£ et al. Yueyatang congshu ń▓ĄķøģÕĀéÕÅóµøĖvol. 15. Taipei: Huawen shuju, 1965.

- ____. Fuchuzhai wen ji ÕŠ®ÕłØķĮŗµ¢ćķøå. Beijing: Beijing University, 2023.

- Weng Shukun ń┐üµ©╣Õ┤æ. Haidong jinshi lingji µĄĘµØ▒ķćæń¤│ķøČĶ©ś [Miscellaneous Notes on Korean Epigraphy]. KwachŌĆÖ┼Ån: Weng Gwacheon Cultural Center, 2010.

- Ye Changchi ĶæēµśīńåŠ. Yu shi Ķ¬×ń¤│. Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan Ķć║ńüŻÕĢåÕŗÖÕŹ░µøĖķż©, 1968.

- Yi Haeng ’¦ĪĶŹć (1478-1534). Sinj┼Łng Tongguk y┼Åji s┼Łngnam µ¢░Õó×µØ▒Õ£ŗĶ╝┐Õ£░ÕŗØĶ”¦ [Revised and Expanded Edition of Survey of the Geography of Chos┼Ån], Kyujanggak edition.

- Yi, PŌĆÖungmo. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£A Study of the Writings of Weng FanggangŌĆØ ń┐üµ¢╣ńČ▒ĶæŚĶ┐░ĶĆā.ŌĆØ Bibliography Quarterly µøĖńø«ÕŁŻÕłŖ 8, no.3 (1974): 39-45.

- Yi U µØÄõ┐ü. Taedong k┼Łms┼Åks┼Å Õż¦µØ▒ķćæń¤│µøĖ [Sourcebook of Metal and Stone in the Great East]. 1668.

- Comparison of transcriptions of Mujangsa Stele at the National Institute of Korean History database. https://db.history.go.kr/ancient/level.do.

- Comparison of the Four Copies of the Lanting Preface. https://patricksiu.org/four-imitation-copies-of-lanting-xu-ĶśŁõ║ŁÕ║ŵæ╣µ£¼Õøøń©«’╝ē/.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by