Abstract

This article examines the non-textual communicative functions of mokkan µ£©ń░Ī (wooden inscribed documents) in early Korean writing culture, framing them not merely as textual carriers but as objects which material and aesthetic properties played a central role in meaning-making. While existing scholarship often prioritizes deciphering textual content, this study emphasizes the visual, tactile, and contextual dimensions of mokkanŌĆöincluding their shape, size, texture, inscription method, and spatial orientationŌĆöas active agents in the adaptation of Sinographic writing. It argues that woodŌĆÖs pliability enabled a culture of writing deeply intertwined with experimentation and sensory engagement. From notation tags and practice multi-surfaced rods to carved amulets, mokkan embodied social, religious, and administrative functions beyond the semantic meaning of the script. By situating mokkan within broader East Asian material traditions, the article lays out a preliminary groundwork that underscores the importance of medium-specific aesthetics and tactile interactions in the formation of early Korean literacy and textual culture, revealing how writing was experienced as both a visual and bodily practice.

-

Keywords: mokkan µ£©ń░Ī, material culture, Sinographic writing, early Korea

ą¦č鹊 ąĮą░ą┐ąĖčüą░ąĮąŠ ą┐ąĄčĆąŠą╝ ŌĆö ąĮąĄ ą▓čŗčĆčāą▒ąĖčéčī č鹊ą┐ąŠčĆąŠą╝

If itŌĆÖs written with a quill, it canŌĆÖt be cut out with an axe

Russian proverb

Introduction

The adoption of Sinographic writing in the Korean peninsula was a dynamic process characterized by continuous innovation, reinvention, and localized transformation. It was not a carbon copy of an existing writing system simply transplanted from one geographical region to another, but a complex phenomenon shaped by regional linguistic features and evolving cultural and social contexts. Wooden inscribed surfaces,

mokkan µ£©ń░Ī, as one of the textual mediums, acted as an active participant that afforded the adaptation of a new script in the Korean peninsula.

1 The physical shape of the

mokkan (e.g., narrow strips, broader planks, multi-sided surfaces), its size, texture, text organization and format as well as how the wood was physically manipulated (e.g., tied, carried, displayed) can all convey non-textual information. Likewise, the very act of choosing wood over other writing surfaces carried non-textual significance. The variability of shapes and visual characteristics of the medium conveyed the experimental aspect of the act of writing revealing the non-passive function surrounding the act of writing. By comparison with the use of other mediums, the paper establishes the role of wood, specifically as it was used in Korean context as a writing media.

To explore non-textual communication and the material dimensions of mokkan, this paper begins by reconsidering the fundamental functions of writing, foregrounding its role as a tool of notation, practical record-keeping, and in putting together binding agreements. It turns to the earliest discovered examples of the emergence of writing in China, particularly oracle bone inscriptions, which elevate writing beyond mere notation to a medium of ritualized promiseŌĆöimbued with authority and sacrality. In these early contexts, the act of inscribing served not only to record but to confer legitimacy, becoming a symbol of status and ritual competence. Building on this premise, the paper draws a comparison between Chinese and Korean developments, noting that while the script in China formed based on preexisting cultural aesthetic forms, the Korean case did not develop new forms but represented a more adaptive encounter. The Sinographic writing system, introduced from outside, was appropriated within distinct cultural and linguistic contexts, prompting a period of experimentation in both form and function. Mokkan served as a versatile medium not only for textual communication but also for non-textual expression and symbolic function. As a material form, wood allowed for significant variation, unlike the more rigid conventions of bamboo or stone. This paper explores how different shapes, sizes, and inscriptional strategies of mokkan were adapted to specific communicative, administrative, and even performative uses in early Korean contexts.

The paper argues that

mokkan in early Korea were active material agents that mediated meaning through their visual form, sensory properties, and ritual contexts, challenging text-centric views of early literacy. I examine an inscribed object not only from a visual perspective but also consider other sensory input/output, such as texture, as a source of a significant piece of information and meaning in inscribed objects for the readers of such objects.

2 How did

mokkan function not only as writing surfaces but as communicative objects with aesthetic, ritual, and tactile dimensions?

By exploring mokkan as both text and object, the article highlights how Korean adaptations of the Sinographic script were deeply entangled with local material culture and embodied practices. In doing so, it challenges conventional notions of writing media and underscores the integral role of the medium itself in the production, perception, and social life of early Korean texts.

Marking and Notation: Organization and Binding Power

As complicated as the topic of writing, let alone the origins of writing, could be one way to see the development of writing (especially at the initial stages) as arising out of need for a marking or a notation system. The organizational system that was purposedly introduced to make oneŌĆÖs life or work easier and has simple and visually identifiable features allowing for the ease of use. Notation systems seem to be rather common and vary from smaller to bigger scale based on the number of users and symbols involved. Below is an example of an illiterate man in Russian village of late nineteenth century who manages his business by developing his own notation system of the goods in his possession:

Ivan is illiterate, he does not know how to write, and yet he is in charge of a barn ŌĆ” Ivan noted all his accounts, he used to notch them out on tags, that is, four-sided sticks, which he had separately for each item, but now he writes with a pencil on narrow pieces of thick paper, using special letters, crosses, sticks, circles, dots, known to him alone. In the evening, when giving his report, Ivan takes out a piece of paper, examines it for a long time and, running his finger over it, and then begins: for the table, 2

pood of flour, 3

pood of barley, 1

pood of lard, 15

pood of corned beef, etc.

3

This is an example of two notation systems, showing a transition from one system to another as well as from one medium to another. It is worth noting that before tracking his goods by writing symbols on paper, Ivan used to organize his work by carving notches on multi-sided wood tags. Either of the systems he used does not have high endurance being highly personalized as it can be deciphered by only a single individual and the range of meanings being quite limited as it is very task specific.

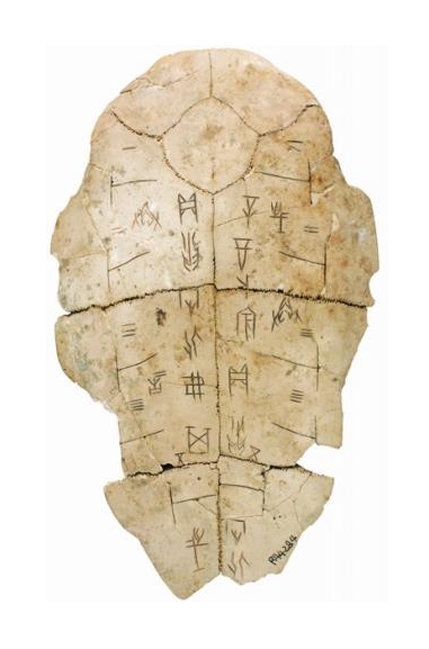

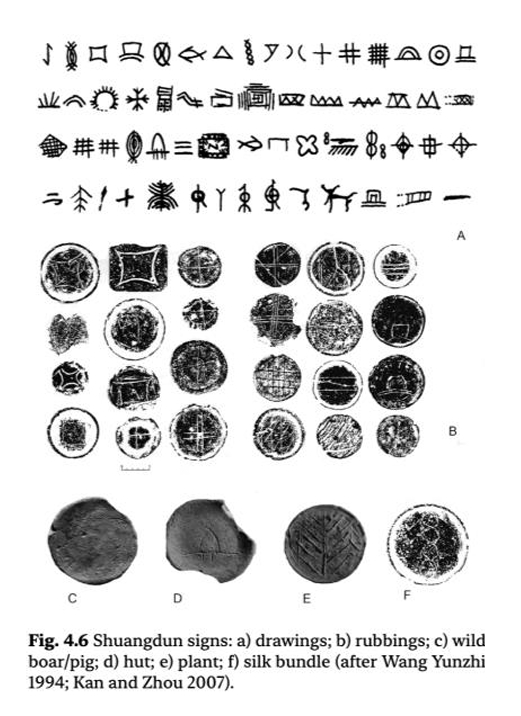

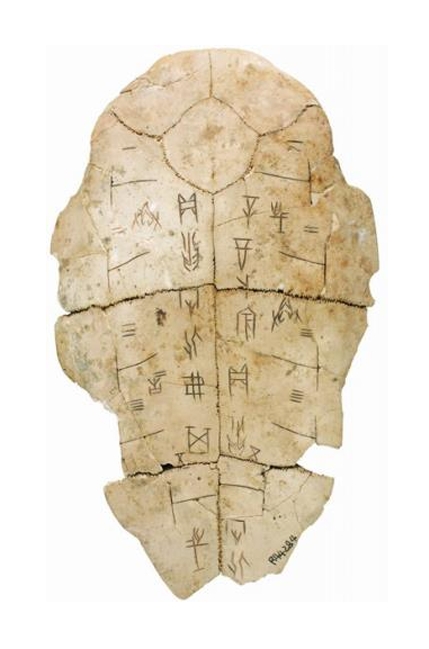

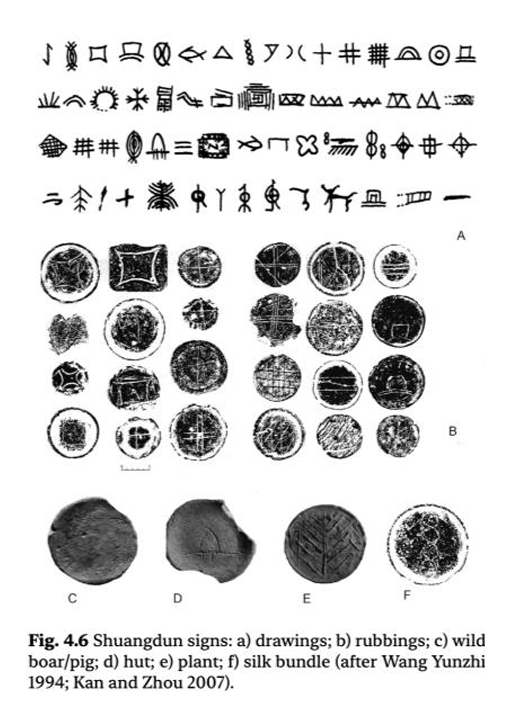

Markings, incisions or interactions with objects, such as wood or clay, seem to be a common preliminary step before application of text to the surface. There are similar examples of singular symbol markings on pottery from Neolithic sites in China near Huai river dated to 6000 BC (see

Figure 1). Since it is not clear what the symbols conveyed: for example, whether they were the indications of the contents of the pottery vessel or the maker of the vessel, it is another example of private interactions with the medium. All things equal it could also be a marking of no semiotic significance, like a doodle, that the type of material allows to create and have one to play and experiment with.

According to early Chinese sources on development of writing in China, prior to characters people made use of several notation systems, including rope knotting (

jiesheng ńĄÉń╣®) and trigrams system. There is not much archaeological evidence of rope knotting existence, but it is plausible that it might have been a simple notation system or mnemonic device based on different number and size of knots.

4

In high antiquity, [government] was regulated by tying knots. In subsequent ages, the sages changed it to written contracts/bonds. By means of these, the hundred officials were regulated, and the myriad people examined.

õĖŖÕÅżńĄÉń╣®ĶĆīµ▓╗, ÕŠīõĖ¢Ķü¢õ║║µśōõ╣ŗõ╗źµøĖÕźæ, ńÖŠÕ«śõ╗źµ▓╗, Ķɼµ░æõ╗źÕ»¤.

5

Like IvanŌĆÖs example above, albeit on a much larger scale, the passage describes two organizational or notation systems, with a shift being made to a more superior one (since it was done by sages). Starting point is once again a recording system which involved certain interactions and modifications of the medium and then replaced with the one that involves writing things down.

6 There are two important things to note: one is the idea of using a notation system as a binding agreement or to hold one to oneŌĆÖs word and the other is the hierarchical distinction between the systems with the one held in higher regard than the other. Such hierarchy was reflected in later ethnographic descriptions of foreign places from the Chinese historical sources emphasizing the superiority of Middle Kingdom that used the script versus the others who did not possess such technology. A passage from the

Sui shu ķÜŗµøĖ (History of Sui, comp. 636) on descriptions of customs of Japanese archipelago inhabitants notes that quite explicitly, describing the people making use of a lesser systems before the introduction of script through Buddhist scriptures from Korean kingdom of Paekche:

Wo people ŌĆ” They did not have written script, they only notched wood and tied knots.

ÕĆŁõ║║ ŌĆ” ńäĪµ¢ćÕŁŚ’╝ī

Õö»Õł╗µ£©ńĄÉń╣®7

Similar rhetoric is found in accounts on the other areas as well. But while explicitly the possession or absence of the Sinographic script technology did ascertain a higher status of the regions that had it, it was an important piece of information from the practical point of view. It was essential for the Chinese side to establish a reliable way of communication with the neighboring regions to ensure diplomatic and trade agreements are followed in the realm of international relations. For example, ethnographic notes on Korean kingdom of Silla from the

Liang shu µóüµøĖ (History of Liang, comp. 635)

8 also explicitly stated that due to the absence of the writing system, wood carving notation was used to make agreements

weixin ńé║õ┐Ī:

Silla ŌĆ” they do not have written script, and notch wood to serve as a guarantee. Their language is understood after relying on that of Paekche.

µ¢░ńŠģĶĆģ’╝īŌĆ” ńäĪµ¢ćÕŁŚŃĆü

Õł╗µ£©ńł▓õ┐ĪŃĆéĶ¬×Ķ©ĆÕŠģńÖŠµ┐¤ĶĆīÕŠīķĆÜńäēŃĆé

9

The marks in wood are described to function as a sort of covenant or binding agreement between the two parties. Simply put instead of signing oneŌĆÖs name (because there were no letters to do so), one would carve wood to fix the agreement. And instead of an unreliable agreement in words it would be fixated in a more permanent fashion. The use of notched wood as a marking system seemed to be a prevalent and universal choice to mutually confirm the agreements:

Huaguo is another branch of Jushi. ŌĆ” They do not have written script and use wood to make contracts. ŌĆ” Their spoken language is understood after relying on translations from Henan people.

µ╗æÕ£ŗĶĆģ’╝īĶ╗ŖÕĖ½õ╣ŗÕłźń©«õ╣¤ŃĆéŌĆ” ńäĪµ¢ćÕŁŚ’╝īõ╗źµ£©ńé║ÕźæŃĆéŌĆ” ÕģČĶ©ĆĶ¬×ÕŠģµ▓│ÕŹŚõ║║ĶŁ»ńäČÕŠīķĆÜŃĆé

The last example below provides a more extensive description of the practice and the use of notched wood agreements in governing of smaller areas. Therefore, such information on communication was crucial for the dealings with the neighbors that required agreements. In this case, carving wood, its manipulated texture becomes a source of information in addition to the visual and probably also auditory one as arrangements are initially made orally with the help of translators (therefore language information is also included in the description passages).

Wuhuan are Eastern Hu ŌĆ”. They always choose to recruit the ones who are brave and strong and can arbitrate disputes and mutual assaults as chieftains, with every encampment having a local leader [position], which is not passed by hereditary succession. Several hundred or thousand encampments make up one tribe. When the elder has something to announce/needs to call someone, he notches wood to use it a guarantee, which is circulated around the encampments. Despite not having a written script the members of tribe do not dare to go against it.

ńāÅõĖĖĶĆģ’╝īµØ▒ĶāĪõ╣¤ŃĆé ŌĆ” ÕĖĖµÄ©Õŗ¤ÕŗćÕüźĶāĮńÉåµ▒║ķ¼źĶ©¤ńøĖõŠĄńŖ»ĶĆģńł▓Õż¦õ║║’╝īķéæĶÉĮÕÉäµ£ēÕ░ÅÕĖź’╝īõĖŹõĖ¢ń╣╝õ╣¤ŃĆéµĢĖńÖŠÕŹāĶÉĮĶć¬ńł▓õĖĆķā©’╝īÕż¦õ║║µ£ēµēĆÕżÕæ╝’╝ī

Õł╗µ£©ńł▓õ┐Ī’╝īķéæĶÉĮÕé│ĶĪī’╝īńäĪµ¢ćÕŁŚ’╝īĶĆīķā©ĶĪåĶĽµĢóķüĢńŖ»ŃĆé

10

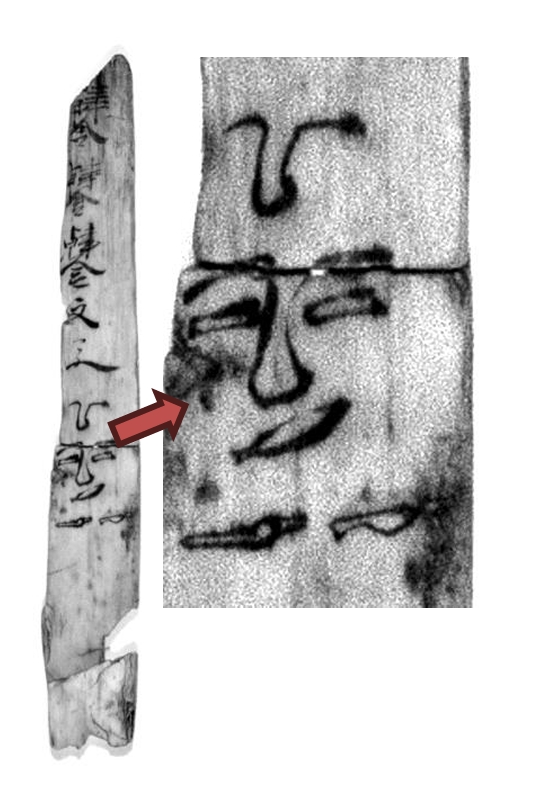

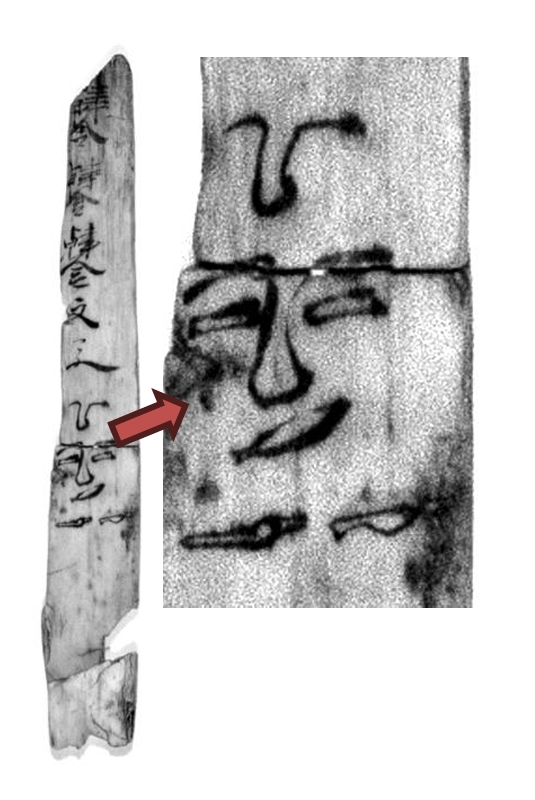

Figure 2 is an example of a carved

mokkan excavated in Paekche capital site of Sabi µ│Śµ▓ś (Kwanbung-ni Ļ┤ĆļČüļ”¼ 286

mokkan). The carving looks like a stamp or a signature of sort with the top writing yuyi ÕĄÄÕżĘ. While opinions differ on whether these two characters refer to a Tang military commanderŌĆÖs title derived from a place name or a Paekche place name from which the title was derived, it is commonly interpreted as a record related to the Tang. Such stamp potentially carried identification or verification purposes. Research suggests the tablet might have been used as a kind of access certification for local officials entering the Paekche palace.

11 Despite having written characters on the wooden tablet, the modification of the texture by carving into it seemed to be necessary for the object to be properly recognized by both sides and communicate that it was a valid entity.

This practice of permanently marking the material that is visually prominent and has a distinct texture, like carving of wood, to signify a mutual promise echoes similar developments in the use of oracle bones as earliest instances of writing in China. Despite the application of written script, it is the medium and how it was initially processed and used that served a primary function to fix a result or desired event. The interaction with the oracle bone as a medium, such as making and interpreting a crack, incising the message and the outcome served as a communication channel with the ancestors solidifying the oral aspect of the ritual in the body of the medium which constituted a promise.

Prestige and Permanence

While it is possible to manage a smaller community via oral communication and simple recording systems, the further development of the society, expansion of its size and technological advancement required a consistent tool to record a spoken language to ensure the reliability of transmission and consistency of the message contents. At some point the need to write something down (versus saying it directly) arose to pass information over a distance or time since the addressee was not readily available. That is a notation system that directly reflects the sounds of spoken message so it can precisely reproduce the auditory experience of hearing it being said. Writing indicated a social complexity where writing can be chosen as a stable communication method and was used as a consistent archival system.

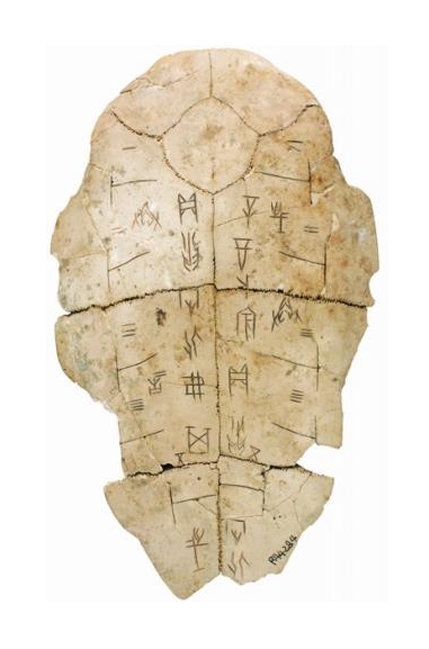

12 The earliest known body of writing in East Asia that has been preserved to the present day appears on animal bones (e.g. ox scapulae) and turtle plastrons, which were used as a writing medium in the state of the Late Shang dynasty (c. 1200-1050 B.C.) and are collectively known as oracle bones ńö▓ķ¬©µ¢ć. Oracle-bone inscriptions are regarded as the earliest writing system in China because it was a consistent, long-lasting system to record the spoken language recognized by a large-enough group of users (while still very limited to scribes, diviners, king and his closest associates and kin). Given the highly specialized nature of oracle bones use, it is likely that other writing mediums were also in use but simply did not survive the course of time

.

The oracle-bone inscriptions were divination records that were part of a complex religious ritual of ancestral communication which involved cracking the bone with an intense heat source

13 and using the cracks to interpret a specific situation or answer a question. Both the questions and/or interpretations were most of the time incised on the surface next to the crack made (and often filled with red or black ink, in some cases just written over with a brush). David Keightley argues that writing in this context was not merely a tool for recording language but a performative, materially anchored act which was closely tied to ancestor worship, ritual divination, political power, and the visual codes of elite art. The result of listening to and interpreting the voices of ancestors in a shape of cracks

14 were fixed in writing that recorded the interpretation validating the offerings to please the ancestors which in turn signified the ancestors validating the rulerŌĆÖs right course of action and legitimacy.

15 The act of producing cracks and carving inscriptions onto turtle plastrons and ox scapulae was bound to ritualized divination practices and to ŌĆ£fixŌĆØ divine will forming a covenant.

From the logistical challenges of acquiring the medium to the intricate demands of preparing the surface, the complex technical process of producing the crack, and carving esoteric graphs into rigid bones, every stage of the process was labor-intensive and highly specialized. Using oracle bones as a medium poses a paradox: while they served as a communication tool with the ancestors, every aspect of the production process rendered the final product visually inaccessible and impossible to interpret to the most. Aesthetic complexity and physically arduous act of modifying the object elevated the prestige of the object, the ritual act it was part of as well as the hierarchical standing of the ones who were part of it. Ability to interact with such objects or even just be present around them signified prestige, demarcating an exclusive and elitist circle with those of higher social status.

16 Likewise, the written script, even outside the religious context, deeply entangled with ancestor worship, aesthetics, and semiotic sophistication acquired a status of elitist and exclusive skill reinforcing social hierarchies.

The time and resources that goes into the medium preparation, the circumstances of its use (ritual practice) as well as the physical characteristics of the medium itself not only influenced the social perception of the written text as well as its form and shape.

17 Among the early media for writing in China, stone steles came the closest in conveying the sense of the ritualistic authority that was embedded in the oracle bones. Characteristics of production, such as intensive labor, high skill investment, and difficulty of the inscription process, contributed to the sense of authority. There were several differences, such as the obvious size discrepancy between the mediums and oracle bones being discarded after certain number of uses unlike stone that was intended to stay forever.

18 Most importantly, however, it was the visibility aspect ŌĆō the type of the material, its physical characteristics and the way it was processed and placed, stone steles were intended to have an audience to communicate its message both in explicit and implicit ways, running opposite to the exclusivist nature of oracle bones.

Stone steles conveyed a sense of authority and was one of the tools by Han 漢 dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) rule to establish its permanent presence in the new areas. Erected in high places upright standing stone steles with vertically written text provided higher visibility. The form, font shapes, and size conveyed ritual and political authority, possibly without requiring the text to be read or understood to grasp its significance.

19 Due to the expensive nature of stone production and sheer size of the material, the ŌĆ£valueŌĆØ of incised stone was visible. Stone symbolized durability and strength, associated with long-lasting permanence, a concept applied to commemorative steles for the deceased, aiming for timelessness and immortality.

20 Based on the type of writing medium chosen, the medium based on its physical characteristics and the way it was displayed and interacted with provided a non-textual layer of meanings communicated without considering the written text at all. Wood, bone, bamboo, and stone while sharing some similarities were highly context-dependent and all differed in how they were perceived.

Writing in China developed in close connection with ritual and cultural code system that found reflection in the way writing system was formed. In the case of Korean peninsula, those characters were integrating with the spoken language as well as a local coded system of artistic expression and understanding of the world. The physical tangibility of wooden objects, its variegated texture and surfaces allowed for a sensory experience of the abstract text, the bodily nature of knowledge.

Ephemerality and Portability

The introduction of Sinographic script to the Korean peninsula began with the expansion of the Han dynasty into the northern part of the peninsula in 108 BC under Emperor Wu µ╝󵣔ÕĖØ (r. 141-87 BC). This led to the establishment of bureaucratic centers in the area, which were also centers of textual production, allowing for the gradual introduction of the script.

While on its own writing served a practical function of communication and bureaucratic organization in the newly formed areas, writing, especially in the form of Chinese classical texts, was a tool of influence and considered a prestige export product. It signified a higher social status for the local elite, as evidenced by the findings of the Analects Ķ½¢Ķ¬× chapters inscribed on bamboo strips dated around mid-first century BCE in Tomb 364 at Ch┼Ångbaek-tong Õ╣│ÕŻīĶ▓×µ¤Åµ┤×õĖēÕģŁÕøøÕÅĘÕó│ in Pyongyang, North Korea

21 as well as the depiction of scribes and paraphernalia associated with the act of writing in mural paintings of Anak tomb No.3 Õ«ēÕ▓│õĖēĶÖ¤Õó│, North Korea.

22 Thus, any means of possession of prime examples of written word via materials like bamboo acquired an association of prestige.

23 Bamboo strips that required much easier process of production compared to that of stone offered portability, allowing valuable items to be kept close and ŌĆ£transferŌĆØ its status to the owner. The visual outline of the writing medium or even its visual representation could suffice to convey this value, regardless of textual content, due to a formed visual association. As discussed above, erecting inscribed stone steles was an effective way to exert a solemn aura of invisible and overseeing permanent influence as well as to provide exposure to the new script. Prestige of the new writing technology and authority of the exotic and revered symbols were conveyed by the medium of stone and its preparation process. However, the same aspects of the material (sheer size and weight) that insured a permanent and long-lasting impression limited the moveability and exposure to the object. While stone steles conveyed lasting presence, authority, and the memory of those who commissioned and possessed them, it was not possible to possess the medium or easily interact with it, it lacked portability and personalization.

During the Han dynasty, bamboo and wood were standard materials used for writing short and long messages (predominantly bamboo, especially for longer texts). Longer documents, such as administrative documents, imperial edicts, and classical writings, were often inscribed with ink on narrow bamboo strips usually with one line of characters of uniform size and length. Multiple bamboo strips were bound together with cords and rolled in a bundle. Bamboo provided relative portability and easiness of storage; it was also not as expensive compared to silk, for example. After the first-second centuries CE, paper gradually replaced bamboo and wood in mainland China. However, local soft and pliable wooden surfaces

24 or

mokkan continued to be used as a writing medium in the Korean peninsula from around the fourth through the eight centuries, and even later, despite paper availability.

25 This suggests a specific role of wood in the Korean context of the adaption of Sinographic script.

While the portability aspect of

mokkan26 and the fact that it contained Sinographic script could imply by analogy that they carried on similar values of prestige and value, it was not the case. Furthermore, in many of the cases the text inscribed with ink never stayed the same and was scraped off completely combined with parts of separate texts or replaced entirely by another text, sometimes multiple times.

27 There seemed to be no intention to preserve the text on

mokkan for a long time or use

mokkan for archival purpose. The ability to easily carve off text and to keep writing and rewriting the content on wood meant that the lasting permanence of the text was not the focus. Overall, not a lot of time was required to prepare the medium surface for writing, in some cases resulting in rugged and uneven texture and shape which could be continuously altered during the interaction with the medium as the text was shaved off. Also, after

mokkan was not in use it was simply discarded. This contrasts with the durability and permanence associated with stone steles and perceived higher value of inscribed bamboo scrolls and later, paper.

Despite being produced and used as a writing medium it almost seemed like that the written word was treated to a point of contempt. This seemed counterintuitive considering that the written script was a new valued technology of which one would want to preserve every example to learn from, committing to memory every instance of precious writing examples. And as I emphasized above, it held an inherent prestige value as it was transferred from mainland to Korean peninsula. However, what differentiated

mokkan as a medium were its reusability and disposability features. The value of

mokkan came from the easiness to remove the text to rather than preserve it permanently which also removed the solemn and exalted treatment of the written text forever ossified in the medium. The interaction potential afforded by the pliability of the wooden material offered experimentation possibilities of different ways to work with the text. Both the writing medium and the excitement of the newly introduced technology of writing allowed to experience the physical act of writing itself rather than focusing on what the content was. Act of writing by engaging with the material, even by just repeatedly scribbling one symbol, contributed to memory retention and solidification of knowledge.

28

Interaction and Experimentation

Unlike bamboo, Korean mokkan exhibited a huge variability in shapes. The rigidity of narrow bamboo planks did not allow for many alternative spatial choices which was paralleled in the top-down vertical grid type of organization of text on paper. The rigid shape of mass-produced bamboo strips that were predominantly used as a writing medium focused on the practical delivery of the inscribed text. Places that did not have bamboo readily available, such as northwestern areas of China, which used local wood as a medium for writing but featured a much wider variety both in the medium shape and text format. Korean mokkan were produced on a smaller scale compared to mass-produced Chinese bamboo strips, possibly due to the availability of other media like paper. In the Korean peninsula in addition to wooden narrow strips, longer text was oftentimes fitted on multi-surfaced rods or wider wooden planks which allowed more columns of text of various sizes. It was also common to further process the wooden planks or rods by piercing, carving or sharpening them in order to carry, hang, or stick it into a surface. In a few examples, the text was carved out instead of being inscribed with ink. Korean mokkan had distinct visual aspects reflecting how much the material was interacted with which made it stand out from other mediums.

Shape and Function

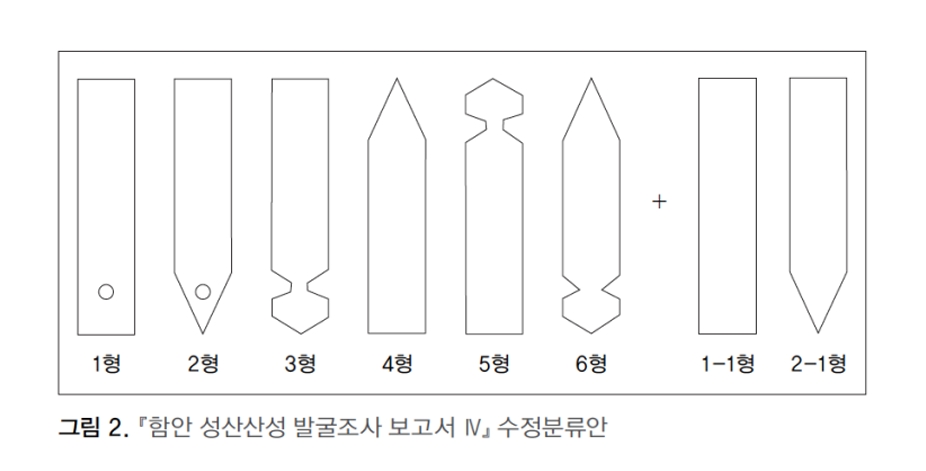

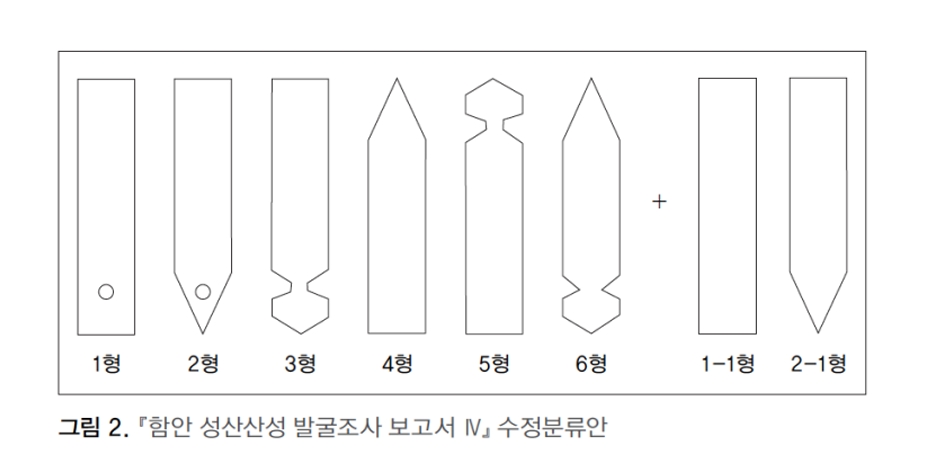

Mokkan allowed for much freedom in regards to spatial organization of the text, rewriting of the text as well as its content. The material itself, its shape, and physical modifications actively contributed to the type of message conveyed. This went beyond mere textual content, revealing insights into the social role of writing and the circumstances surrounding its production and use. Tags and labels (Kor.

kkoripŌĆÖyo mokkan) used for shipments, tax purposes or supply management which could be considered as a type of a notation system, had a distinct visual presence. While some were as simple as compact rectangular tags, majority featured a range of modification options to the material to indicate the purpose: v-shaped grooves carved out at the right and left sides at the top or bottom; single hole piercings for attachment with rope or string as well as sharpening at one of the ends to stick into a surface for display. The shape directly supported or reflected the purpose of the object. Such tags were a combination of two notation systems: notched wood to roughly indicate a category of

mokkan use and characters inscriptions for cataloguing. For a good example of such a variety of shapes refer to

Figure 4 below which shows Kaya region Haman Seongsan Mountain FortressŌĆÖs ÕÆĖÕ«ē Õ¤ÄÕ▒▒Õ▒▒Õ¤Ä wooden slips understood to be the tags of food records consumed by the people who were mobilized to build the fortress.

Wider wood was used to allow two columns of characters to fit more text, for example, for document drafting. Some of them also include small holes pierced at one side.

29 Lee Sangil suggests that after

mokkan had completed their administrative functions they were pierced with holes as one of the ways to mark the wood prior to disposal. It is presumed that pierced holes were used to tie

mokkan together either to temporary store them for management or recycling purposes prior to disposal. This indicates that the wood modifications, such as pierced hole, did not necessary communicate one single meaning and depended on the point of life cycle of the

mokkan. The reason to discard

mokkan was to prevent misuse as they included sensitive or important information. It was common to cut the used

mokkan marked for disposal into two or more pieces. This practice was also observed with Japanese

mokkan.

30

In addition to narrow strips and wider planks, longer text was fitted on wider wooden planks or multi-surface three-dimensional rods (Kor.

tagangmy┼Ån mokkan ÕżÜĶ¦ÆķØ󵣩ń░Ī, referred to as

gu Ķ¦Üin Chinese context) which allowed more columns of characters of various sizes. While multi-surface precedents existed in China for student copying and official documents, this variability was unique to Korea and not seen much in Japanese counterparts.

31

The multisurface rods in Chinese context were mainly used for memorization of the text. Usually, the rod was made in such a way that it could be placed independently on a flat surface to exhibit one side with the text while obscuring the content of the other sides in order to recite it and potentially practice writing it (also for calligraphy practice). It was rotated when needed. Several of them could be tied together to accommodate longer text by piercing a hole at the top and stringing them together.

32 The standing aspect or at least the intention to display the text horizontally reminds us of the visibility qualities of the stone steles which conveyed the prestigious nature and thus authority of the text. But the material and shape of the medium (wooden rod) reminds us of the fact that it was not an edition of the classical texts (written on one side of bamboo and laid flatly on surface or held in hands) but an aid in learning despite having a venerable text inscribed.

There are very few

mokkan that have inscribed quotations from Confucian canonical texts, one of the examples include a relatively recently excavated Ssangbung-ni ķøÖÕīŚķćī 56

mokkan no. 1 from Paekche. It has a short excerpt from Analects written on a multi-surface rod.

33 There are many more examples of multi-sided

mokkan that did not include any reference to the Classics but were used for the compositional practice ŌĆō there was much more freedom in spatial organization and rewriting. Sturdy but malleable wood allowed to easily carve off the text over and over again, revealing a clean surface ready to be used. The modification process and such close involvement with the media made the experience memorable on a tactile level that was paralleled in inscribing the material with text. It facilitated reuse and contributed to easiness of continuous practice and memorization. Once the content or skill was committed to memory the medium enabled entirely new content. Examples include the Kungnamji Pond Õ««ÕŹŚµ▒Ā

mokkan No. II-1 from Paekche (see

Figure 5). Judging from the shape of the material and the content of the text (one side features only the repetition of character wen µ¢ć) it was used purely for compositional practice without valuable content. Wood as a material is quick to adjust when the inscribed text is not of such high value. Likewise the text is inscribed following the natural bend of the wood. In case of Kungnamji Pond

mokkan, the wood is crooked and is barely processed in any way ŌĆō providing a bare minimum to be practiced with. Unlike the Chinese example above, since it is not straight it was not possible to place it on a flat surface and can only be held by hand. It is also worth pointing out that the quality of calligraphy on this and majority of other

mokkan examples are not outstanding in any way and actually lack any aesthetic value that visual characteristics of the text were not the prime target.

At the same time, just like with the shape of

mokkan, the spatial organization, arrangement and form of the text can visually bring attention, communicating more efficiently the purpose of the object. As one can alternate the size of the letters and divide the columns with ink on paper to make the content more straightforward, similar visual effects could be achieved in

mokkan. Spacing between the characters, visual distinction from front and back, size of the letters, and use of certain expressions (or marks, like checkmarks) are some of the organizational devices found on some of the

mokkan that were used to divide the content.

34 The format of the text coordinated with the shape of the material reflected the interactivity purpose. Due to the flexibility in its structural adjustments that could be done,

mokkan were utilized for a variety of purposes visually communicating the practical aspect of experience with the script.

Opposite to the image of solemn and rigid nature of prestigious elite script, wood by the characteristics of its material and circumstances of its use introduced a playful aspect of interacting with and exploring the new technology. It was relatively accessible and cheap; it was user friendly and did not require to be fully literate or advanced skills in writing. As Marjorie Burge convincingly argued, the value of some

mokkan came from the ability to remove the text and reuse the material, emphasizing the interactive aspect of working with the text and the act of writing itself, rather than the preservation of the specific content.

35

In China, the development of writing was closely aligned with a broader system of religious aesthetics and ancestral worship and communication. Likewise, in the Korean context, the engagement with the new script could also be conceived in the similar way ŌĆō blending with the local traditions and aesthetic values with the text contributing an efficacious function in the local belief system.

A phallus-shaped multisided rod Neungsang-ri ķÖĄÕ▒▒ķćī 295 found at Paekche temple site (

Figure 6) shows the dynamic nature of text-medium adaptability to the social circumstances as expressed in the material which afforded that dynamics. It is not part of the bureaucratic housekeeping but provides a glimpse in a ritual aspect of the daily life. The shaping of the top wedge looks similar to the structural decision of shipment tags that have v-shaped groves on the sides used to tie a rope around it. Hole at the bottom shares similarity with holes pierced in

mokkan used to tie several

mokkan together or marked for disposal. Some scholars conjectured that the hole indicated that the

mokkan was part of a structure with a wood peg and pedestal that allowed the object to stand straight.

36 It also has a sharpening at the bottom usually used was for sticking into something for display, as pointed out above. Potentially, such sharpening could be used as a handle for the easiness of holding when writing something down. In the case of this

mokkan, we see an imaginative transformation or morphing of several different structural decisions to create a desired function that would be reflected in the shape, form as well as textual content.

The script likewise becomes in tune with the medium. It could move around the surface to match the woodŌĆÖs changes in shape, enhancing the textŌĆÖs function and merging it more tightly with its medium. On one side we have both carved and inscribed text with the latter: ŌĆ£Road contribution erect erect erectŌĆØķüō ńĘŻ ń½ŗń½ŗń½ŗ. The action of erecting or placing up

li ń½ŗ the

mokkan directly correlated with the text that was calling for propping up the medium

li ń½ŗ and establishing the ritual road offering, Tohy─üngche ķüōķźŚńźŁ. The orientation of the text is also significant. For example, on the other side there are three carved characters with the character for ŌĆ£HeavenŌĆØ tian Õż® written ŌĆ£upside-downŌĆØ if the

mokkan was placed up. One of the possible implications is that it was addressed to Heaven and thus was rotated so it can be read from the sky above while ń½ŗ was written to indicate that it was ŌĆ£placedŌĆØ on the spot.

37 Therefore, the spatial orientation of the text was not random and contributed to the ritual intent. Lastly, it is significant that parts of the text are carved in versus being inscribed with ink replicating the stone steles format as well as amplifying the idea of sealing the ritual promise and binding agreement to fulfill the ritual intention (similar to oracle bones as well) that can be displayed as it is standing upright. We get a compacted mini version of a number of meanings that is portable and can be carried around. Meaning of authority embodied by stone is now executed in the wood in order to boost the ritual aspect and function that the

mokkan carries. The ritual itself possibly refers to the road deity ritual which was done for safe travel or to guard from spirits entering specific locations. The road deities are common practice in Japan,

dosojin ķüōńź¢ńź×, where many are made of stone.

38

The playfulness embedded in the experimentation with the material could also be found in the experimentation with the inscribed text. An example from SillaŌĆÖs Ky┼Ångju Anapchi ķøüķ┤©µ▒Ā 184

mokkan (

Figure 7), a

mokkan inscribed on both sides and used for compositional practice, features repetitive inscriptions of the same characters just like in the example of the compositional multisurface rod discussed above. While the wider surface allows to have two columns of text on one side, on the other side the repetition culminates in a smiley face doodle at the bottom of the

mokkan. Just like with the Neolithic scribbles described at the very beginning of the article, there is no linguistic value in the abstract image but a reflection of enjoyment of interacting with the material while experimenting with the application of the new notation technology. The tiny gesture reveals probing the extent of the abstract borders the new technology can be implemented to afforded by the flexibility of the material.

39

The flexibility in shaping the material led to a distinctive visual manifestation of the medium that connected with and enhanced the textŌĆÖs meaning. It demonstrates how the woodŌĆÖs shape and format reflected cultural practices beyond just the function of writing. Wood as a medium (vs paper, for example) functioned as a practice material for integration of Sinographic writing and establishment of writing culture in the Korean peninsula. The low cost, reusability and inherent properties of wood (e.g. its pliability) afforded the relative easiness of writing application allowing to not only practice writing as a new technology (transmit oral message in written form) but also experiment with its visual manifestations and styles. The object never seemed to be in the final state and kept being modified.

Conclusion

The introduction and adaptation of Sinographic writing in the Korean peninsula during the fourth through eighth centuries CE involved a complex interaction between script, culture, society, and the material medium. Unlike areas where bamboo or paper predominated, Korean contexts saw the sustained and unique use of wood, or mokkan. The pliability of wood allowed for an unprecedented variability in shapes and sizes, including the distinctive multi-surface mokkan unique to Korea.

This flexibility afforded by the medium facilitated a dynamic writing practice. Wood served not only practical functions like administrative records and shipment tags but also as a primary material for compositional practice and calligraphy, allowing for spatial freedom and the easy removal and rewriting of text. The value of mokkan, in some contexts, lay precisely in its reusability and practicality, challenging the traditional association of value with permanence seen in stone or venerated texts on bamboo.

Moreover, the medium actively participated in creating and enhancing meaning. The shapes, the spatial organization of text on the surface, the choice between carving and inscription, and the incorporation of drawings or figurative forms all conveyed non-textual information deeply intertwined with the objectŌĆÖs purpose, whether bureaucratic, educational, or ritualistic. Mokkan reveal a process where the incoming Sinographic script and writing practices were actively blended with existing local cultural meanings and material sensibilities. The material and its modifications were not just carriers of information but integral components of the message and the act of communication itself.

Korean mokkan, through their diverse forms and functions, underscore how a writing medium can be an active and significant participant in the adaptation of a new script, reflecting and shaping social and cultural environments and contributing fundamentally to the creation and amplification of textual meaning. They broke free from some established norms associated with Sinographic writing media elsewhere, demonstrating a unique local development.

In summary, Korean mokkan were not merely passive carriers of Sinographic text. Their material properties, diverse shapes, physical modifications, and contextual use acted as active participants in the communication process, conveying meaning related to ritual, social status, functionality, and the dynamic process of adapting a foreign writing system.

Notes

Figure 1.From Paola Dematt├©, The Origins of Chinese Writing, p. 125.

Figure 2.Kwanbung-ni No. 286 mokkan. National Cultural Heritage Research Institute ĻĄŁļ”Įļ¼ĖĒÖöņ£Āņé░ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņøÉ

Figure 3.Inscribed Plastron Ping 0069. Museum of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica

Figure 4.

Ancient Wooden Tablet with Inscription in Korea ŌģĪ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņØś Ļ│ĀļīĆļ¬®Ļ░äŌģĪ, p. 14

Figure 5.Kungnamji Pond mokkan No. II-1, History Passwords in Wood, Wooden Tablets ļéśļ¼┤ ņåŹ ņĢöĒśĖ ļ¬®Ļ░ä, p. 70

Figure 6.Neungsang-ri 295 mokkan, History Passwords in Wood, Wooden Tablets, p. 15

Figure 7.Kyŏngju Anapchi 184 mokkan, History Passwords in Wood, Wooden Tablets, p. 141

- Allan, Sarah. The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China. Albany: SUNY Press, 1991.

- Burge, Marjorie. ŌĆ£Inscriptive Practice and Sinographic Literary Culture in Early Historic Korea and Japan.ŌĆØ PhD Thesis, 2018.

- Burge, Marjorie. ŌĆ£Wooden Inscriptions and the Culture of Writing in Sabi Paekche.ŌĆØ Asian Perspectives 58, no.1 (2019): 47-73.

- Choi Jang-mi ņĄ£ņןļ»Ė et al. Ancient Wooden Tablet with Inscription in Korea ķ¤ōÕ£ŗņØś ÕÅżõ╗Żµ£©ń░ĪŌģĪ. Gaya National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage ĻĄŁļ”ĮĻ░ĆņĢ╝ļ¼ĖĒÖöņ×¼ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņåī, 2017.

- Copp, Paul. The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

- Dematt├©, Paola. The Origins of Chinese Writing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Engelhardt, A. N. (ąŁąĮą│ąĄą╗čīą│ą░čĆą┤čé ąÉ. ąØ.). From the village. 12 letters. 1872-1887 (ąśąĘ ą┤ąĄčĆąĄą▓ąĮąĖ. 12 ą┐ąĖčüąĄą╝. 1872-1887). St. Petersburg: Nauka, 1999.

- Gentz, Joachim. ŌĆ£The Ritual Meaning of Textual Form Evidence from Early Commentaries of the Historiographic and Ritual Traditions.ŌĆØ In Text and Ritual in Early China, edited by Martin Kern. University of Washington Press, 2005, pp. 124-148.

- HanŌĆÖguk Mokkan Hakhoe ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ļ¬®Ļ░ä ĒĢÖĒÜī. Munja wa godae Hanguk 1 ļ¼Ėņ×ÉņÖĆ Ļ│ĀļīĆ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ 1. Seoul: Juryuseong Chulpansa, 2019.

- Hatch, Michael J. Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790-1840. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2024.

- Hong, Sueng Woo. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Haman Seongsansanseong mokgan-ui mulpum gijaebangsik-gwa Seonghamokgan-ui seosik.ŌĆØ ĒĢ©ņĢł ņä▒ņé░ņé░ņä▒ ļ¬®Ļ░äņØś ļ¼╝ĒÆł ĻĖ░ņ×¼ļ░®ņŗØĻ│╝ ņä▒ĒĢśļ¬®Ļ░äņØś ņä£ņŗØ.ŌĆØ Mokkan kwa munja µ£©ń░ĪĻ│╝ µ¢ćÕŁŚ 21 (2018): 77-98.

- Hong, Sueng Woo. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Hanguk godae munseo mokgan-ui seosik-gwa seosa jaeryoŌĆØ ķ¤ōÕ£ŗ ÕÅżõ╗Ż µ¢ćµøĖµ£©ń░ĪņØś µøĖÕ╝ÅĻ│╝ ņä£ņé¼ņ×¼ļŻī.ŌĆØ Journal of East-West Humanities ļÅÖņä£ņØĖļ¼Ė 19 (2022): 117-152.

- Keightley, David N. ŌĆ£Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China.ŌĆØ Representations 56 (1996): 68-95.

- Kim, Chang-seok. ŌĆ£Ancient Korean Mokkan (Wooden Slips): With a Special Focus on Their Features and Uses.ŌĆØ Acta Koreana 17 (2014): 193-222.

- Kim Seong-sik Ļ╣Ćņä▒ņŗØ and Han Zi-a ĒĢ£ņ¦ĆņĢä. ŌĆ£Puy┼Å Ssangbuk-ri 56-b┼Ånchi Sabi Hanok Ma┼Łl chos┼Ång puji yuj┼Åk ch'ulto mokkanŌĆØ ļČĆņŚ¼ ņīŹļČüļ”¼ 56ļ▓łņ¦Ć ņé¼ļ╣äĒĢ£ņśźļ¦łņØä ņĪ░ņä▒ļČĆņ¦Ć ņ£ĀņĀü ņČ£ĒåĀ ļ¬®Ļ░ä. Mokkan kwa munja µ£©ń░ĪĻ│╝ µ¢ćÕŁŚ, 21 (2018): 341-353.

- Lee Jae-hwan ņØ┤ņ×¼ĒÖś. ŌĆ£HanŌĆÖguk kodae ŌĆśchusul mokkanŌĆÖ ┼Łi y┼ÅnŌĆÖgu tonghyang kwa ch┼Ånbang: ŌĆśchusul mokkanŌĆÖ ┼Łl chŌĆÖajŌĆÖasaŌĆØ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ Ļ│ĀļīĆ ŌĆśÕæ¬ĶĪōµ£©ń░ĪŌĆÖņØś ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ļÅÖĒ¢źĻ│╝ Õ▒Ģµ£ø -ŌĆśÕæ¬ĶĪōµ£©ń░ĪŌĆÖņØä ņ░ŠņĢäņä£-. Mokkan kwa munja µ£©ń░ĪĻ│╝ µ¢ćÕŁŚ, 10 (2013): 119-156.

- Lee Sangil ņØ┤ņāüņØ╝. ŌĆ£Puy┼Å Kwanbungni yuj┼Åk y┼ÅnŌĆÖmot chŌĆÖulto mokkan kwa mokchepŌĆÖum ┼Łi pŌĆÖoeŌĆÖgiyangsangŌĆØ ļČĆņŚ¼ Ļ┤ĆļČüļ”¼ ņ£ĀņĀü ņŚ░ļ¬╗ ņČ£ĒåĀ ļ¬®Ļ░äĻ│╝ ļ¬®ņĀ£ĒÆłņØś ĒÅÉĻĖ░ņ¢æņāü. Journal of East-West Humanities ļÅÖņä£ņØĖļ¼Ė 19 (2022): 153-191.

- Lee Yong-Hyeon ņØ┤ņÜ®Ēśä et al. History Passwords in Wood, Wooden Tablets ļéśļ¼┤ ņåŹ ņĢöĒśĖ ļ¬®Ļ░ä. Seoul: Yemaek, 2009.

- Nienhauser, William H., ed. Grand ScribeŌĆÖs Records, Vol. 9: The Memoirs of Han China, Part II. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Safin, Timur A. ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Piktogrammi v nadpisyah na gadatelnih kostyah (chast 1)ŌĆØ (Pictograms in the Oracle Bone Script [part 1]).ŌĆØ ąŁą┐ąĖą│čĆą░čäąĖą║ą░ ąÆąŠčüč鹊ą║ą░ (Oriental Epigraphy) 36, no.3-4 (2021): 120-133.

- Sanft, Charles. Literate Community in Early Imperial China. Albany: SUNY Press, 2019.

- Shin, Jeongsoo. ŌĆ£Kim Ch┼Ångh┼Łi and His Epigraphic Studies: Two Silla Steles and Their Rubbings.ŌĆØ Journal of Korean Studies 27, no.2 (2022): 199-223.

- Sima Qian ÕÅĖķ”¼ķüĘ. Shiji ÕÅ▓Ķ©ś. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1959.

- Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin. Written on Bamboo & Silk: The Beginnings of Chinese Books & Inscriptions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Wei Zheng ķŁÅÕŠĄ, comp. Sui shu ķÜŗµøĖ. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1973.

- Wu Hung. Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Yao Silian զܵĆØÕ╗ē, comp. Liang shu µóüµøĖ. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1973.

- Yoon Seon-tae ņ£żņäĀĒā£. ŌĆ£Paekche Sabi doseong kwa U┼ŁiŌĆöMokkan ┼Łro pon Sabi doseong ┼Łi an kwa paŌĆØ ńÖŠµ┐¤µ│Śµ▓śķāĮÕ¤ÄĻ│╝ ÕĄÄÕżĘ-µ£©ń░Īņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│Ė µ│Śµ▓śķāĮÕ¤ÄņØś ņĢłĻ│╝ ļ░¢. East Asian Archaeological Forum 2 µØ▒õ║×ĶĆāÕÅżĶ½¢ÕŻć 2 (Chungcheong Cultural Heritage Research Institute, 2006), pp. 250-256.

- ____. Mokkan i t┼Łlly┼Å chun┼Łn Paekche iyagi ļ¬®Ļ░äņØ┤ ļōżļĀżņŻ╝ļŖö ļ░▒ņĀ£ ņØ┤ņĢ╝ĻĖ░ (Seoul: Churyus┼Ång, 2007).

- Yoon, Seon-tae. ŌĆ£ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ÕżÜķØ󵣩ń░ĪņØś ļ░£ĻĄ┤ ĒśäĒÖ®Ļ│╝ ņÜ®ļÅä.ŌĆØ Mokkan kwa munja µ£©ń░ĪĻ│╝ µ¢ćÕŁŚ 23 (2019): 67-84.

- Yun Jae-seug ņ£żņ×¼ņäØ, ed. Hanguk mokgan chongnam ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ļ¬®Ļ░ä ņ┤Øļ×ī (ķ¤ōÕ£ŗµ£©ń░ĪńĖĮĶ”Į). Seoul: Juryuseong Chulpansa, 2022.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by