Abstract

-

Ancient stone inscriptions composed in ancient script ÕÅżµ¢ćÕŁŚ, known as epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢, are confirmed to have been introduced into Chos┼Ån in large numbers beginning in the late sixteenth century. The interest in epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢ during the late Chos┼Ån period stemmed from the fervent enthusiasm for epigraphy ķćæń¤│ and epigraphic compilations ķćæń¤│ÕĖ¢. Starting with the 17th-century envoy mission to Beijing ńćĢĶĪī led by Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun Yi U µ£ŚÕ¢äÕÉø µØÄõ┐ü, Chos┼Ån envoys who admired epigraphy and calligraphy acquired Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć, Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ, and Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ, thus giving rise to the epigraphy fever ķćæń¤│ńå▒ beginning in the 17th century, which extended to the domain of epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢. What is especially noteworthy is that in the late Chos┼Ån period, epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢ were not merely briefly described, but rather were subjected to in-depth analysis and decipherment of characters and texts from a philological standpoint.

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć, the first stone-carved poetic inscription in China, is confirmed to have been introduced already in the 15th century and was brought in repeatedly through 17th to 19th-century envoy missions to Beijing ńćĢĶĪī. Accordingly, Chos┼Ån literati revealed a general philological consciousness by citing works such as Rixia jiuwen kao µŚźõĖŗĶłŖĶü×ĶĆā, Daxing xianzhi Õż¦ Ķłł ńĖŻ Õ┐Ś, and Dijing jingwu l├╝e ÕĖØ õ║¼ µÖ» ńē® ńĢź to investigate the textual transmission of the Stone Drums ń¤│ķ╝ō. Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ is presumed to have been introduced during the 16th to 17th centuries, and it is confirmed that a rubbing µŗōµ£¼ of Shenyubei had already been brought into Chos┼Ån by 1659, as evidenced through a classical Chinese poem by Yun H┼Łk Õ░╣ķæ┤. H┼Å Mok Ķ©▒ń®å (1595ŌĆō1682) identified the edition of Shenyubei purchased by Yi U, Nam K┼ŁkŌĆÖgwan ÕŹŚÕģŗÕ»¼ criticized the cultural value of Shenyubei with striking acuity, and S┼Ång Hae┼Łng µłÉµĄĘµćē synthesized and organized the theories concerning the transmission and excavation of Shenyubei. Moreover, Chos┼Ån literati appreciated the aesthetic quality of the calligraphy in the inscription of Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ from the early stage of its introduction and actively embraced its calligraphic style µøĖµ│Ģ, exhibiting a philological attitude regarding issues such as the authenticity and authorship of the stele.

-

Keywords: Epigraphic Rubbings of Ancient Texts, Shiguwen, ShenyubeiYishanbei, Epigraphic Studies

Introduction

Epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢ are stele rubbings composed in ancient script that faithfully preserve the

graphological structure and artistic value of ancient script and ancient characters. Since the texts in epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts, in terms of their

principles of character construction and

characteral forms, differ entirely from modern Chinese characters, it is necessary to understand the concept and characteristics of ancient script before examining epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts themselves. According to Qiu Xigui ĶŻśķī½Õ£Ł (2002), the transformation process of Chinese script can be broadly divided into two phases: the ancient character stage ÕÅżµ¢ćÕŁŚ and the clerical-regular script stage ķÜĖ┬ʵźĘ.

1 Historically, the ancient character stage spans from the late Shang ÕĢå period to the Qin ń¦” dynasty, and based on formal features, it can be classified into Shang characters, Western Zhou and SpringŌĆōAutumn characters Ķź┐Õ橵śźń¦ŗ µ¢ćÕŁŚ, Six States characters ÕģŁÕ£ŗ µ¢ćÕŁŚ, and Qin characters ń¦”ń│╗ µ¢ćÕŁŚ. These categories encompass script forms such as oracle bone script ńö▓ķ¬©µ¢ć, bronze inscriptions ķćæµ¢ć, large seal script Õż¦ń»å (also called Zhouwen ń▒Ƶ¢ć), and small seal script Õ░Åń»å.

2 Zhang Zhenglang Õ╝Ąµö┐ńā║ (1988) had also previously discussed the implications of ancient script. He stated that the term refers to the script forms of ancient Chinese characters and, in general, encompasses all scripts used before the Qin empireŌĆÖs standardization of writing. In its broad sense, ancient script originated in the Shang period and continued to be used thereafter, characterized by its independence from temporal, spatial, or morphological restrictions.

3

Although the corpus of ancient script materials currently unearthed is vast and diverseŌĆöincluding oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions recorded on ritual vessels such as

ding ķ╝Ä,

pan ńøż,

gui ń░ŗ,

fu ń░Ā, and

jue ńłĄŌĆöthe works that exerted profound influence on the history of calligraphy as epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts are limited to

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć,

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ, and

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ.

4

Meanwhile, epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts written in seal script ń»åµøĖ and other styles are thought to have been introduced to the Korean Peninsula relatively late and only began to circulate widely from the Chos┼Ån dynasty.

5 The imported epigraphic rubbings in ancient script were not only actively embraced as models of calligraphic style but were also utilized as crucial materials for epigraphic studies and philological research. Particularly in the late Chosŏn period, calligraphic styles aspiring to the ancient methods developed in diverse directions. Calligraphers including

Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun Yi U µ£ŚÕ¢äÕÉø µØÄõ┐ü (1637ŌĆō1693) were devoted to the ancient methods of the WeiŌĆōJin ķŁÅµÖē period while also according significant importance to earlier epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts. Moreover, as the achievements of epigraphic studies from the Song Õ«ŗ (960ŌĆō1297), Ming µśÄ (1368ŌĆō1644), and Qing µĖģ (1636ŌĆō1912) dynasties gradually entered Chos┼Ån and domestic research in epigraphy flourished, understanding of ancient epigraphic characters deepened, leading to the emergence of numerous scholars engaged in the study of epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts.

6

This article therefore aims to examine the interest in epigraphy during the late Chos┼Ån period, trace the paths by which epigraphic rubbings of ancient textsŌĆösuch as Shiguwen, Shenyubei, and YishanbeiŌĆöwere introduced, and investigate how Chos┼Ån literati in the 17th to 19th centuries received these works in both epigraphic and philological terms.

Enthusiasm for Epigraphic Studies and Interest in Epigraphic Rubbings of Ancient Texts

Epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts served as exemplary models for the study of calligraphy and as important materials for epigraphy. Although they began to be introduced in earnest during the late Chosŏn period, interest in epigraphy had already persisted on the Korean Peninsula beforehand. While it is difficult to determine precisely when this interest arose, the fact that epigraphic materials from ancient times have been transmitted, along with the growing attention to script forms in the late Chosŏn period, suggests that collections of calligraphic models containing the works of renowned historical figures and stele inscriptions composed of assembled characters were in vogue, and the practice of making rubbings was likely widespread.

7

In the early Chos┼Ån period, interest in epigraphy does not appear to have been particularly pronounced. However, after the widespread destruction of cultural heritage during the Imjin waeran(1592ŌĆō1598) and the Py┼Ångja horan(1636ŌĆō1637), the literati developed a sense of nostalgia for the Era of King S┼Ånjo Õ«Żńź¢ (1567ŌĆō1608), a time when literature and the arts had flourished under royal patronage and interest. This trend began in the early 17th century and deepened following the Injo Panj┼Ång(1623), and the compilation of rubbings of epigraphic texts in the 17th century must be understood within this historical context.

8

Meanwhile, by the mid-17th century, epigraphic texts such as

Jigu lu ķøåÕÅżķīä by Ouyang Xiu µŁÉķÖĮõ┐« (1007ŌĆō1072) and

Jinshi lu ķćæń¤│ķīä by Zhao Mingcheng ĶČÖµśÄĶ¬Ā (1081ŌĆō1129) had been introduced into Chos┼Ån. As a result, scholars with antiquarian and broad antiquity-oriented dispositions engaged in highly active stele collecting as a form of aesthetic appreciation. Subsequently, through the Reign of King Sukchong (1674ŌĆō1720) and particularly following the Reigns of Kings Y┼Ångjo (1724ŌĆō1776) and Ch┼Ångjo (1776ŌĆō1800), epigraphic scholarship came to be pursued in earnest with the reception of Qing-dynasty evidential learning.

9

The representative works on epigraphic texts ķćæń¤│µ¢ć produced in Chos┼Ån between the 17th and 19th centuries can be summarized as follows.

10

As shown in the table, from the seventeenth century onward, certain royal relatives and Yangban literati of the capital actively engaged in collecting rubbings and conducting philological investigations of epigraphic inscriptions, thereby enthusiastically advancing the study of epigraphy.

Although it is difficult to determine exactly when scholars began to take conscious interest in epigraphy and to approach it with philological rigor, it appears that such efforts began as early as the Kory┼Å period. From that time, literati seem to have attempted evidential investigations of Chinese epigraphy. In the late Kory┼Å period, Yi Inno µØÄõ╗üĶĆü (1152ŌĆō1220), upon reading epigraphic records and poetic writings about the stone drums ń¤│ķ╝ō, was so moved that he composed a long poem of twenty rhyming lines

11

The stone drums, located within the temple of Confucius in Qiyang Õ▓ÉķÖĮ, had been transmitted through poetry and writings for nearly two thousand years from the Zhou Õæ© dynasty to the Tang ÕöÉ dynasty. However, they are scarcely attested in historical records and the writings of the various philosophical schools Ķ½ĖÕŁÉńÖŠÕ«Č. Wei Yingwu ķ¤ŗµćēńē® (737ŌĆō792), and Han Yu ķ¤ōµäł (768ŌĆō824) were both deeply knowledgeable about antiquity; yet, although they identified these drums as the stele ńóŻ of King Xuan of Zhou Õæ©Õ«ŻńÄŗ (841ŌĆō782 BCE), they still recorded them in lyrical verse and analyzed them in full detail. Ouyang Xiu also stated that there were three points of doubt concerning the

Shiguwen. I happened to read his writing yesterday at the calligraphy library, and it struck a chord with me, so I composed a twenty-rhyme poem and await the evaluation of gentlemen of later generations.

12

This record confirms that the

Jigu lu by Ouyang Xiu had already been introduced into Kory┼Å and that literati had begun to take interest in Chinese epigraphy recorded therein. Moreover, in the early Chos┼Ån period, Kim Sish┼Łp ķćæµÖéń┐Æ (1435ŌĆō1493) once praised a monkŌĆÖs calligraphy, stating: ŌĆ£His strange tales are mixed with Daoist philosophy, and his brushwork descends from the

Shiguwen.ŌĆØ From this, it can be inferred that not merely written references to the stones drums but actual rubbings of the

Shiguwen had already been introduced into early Chos┼Ån. The stele ńóŻ related to King XuanŌĆÖs hunting expedition, found in the

Shiguwen and extensively documented in works such as the

Jigu lu, as well as classical poems on the same theme by poets such as Wei Yingwu, Han Yu, and Su Shi ĶŗÅĶĮ╝ (1037ŌĆō1101), were widely circulated among the literati of Chos┼Ån. Thus, it seems that the rubbings of the stone drums, namely the

Shiguwen, had already entered Chosŏn prior to the enthusiasm for epigraphy of the seventeenth century.

13

Unlike the

Shiguwen, which had already been introduced in the early Chosŏn period, the

Yishanbei and

Shenyubei began to be imported later, during the late Chos┼Ån period through envoys to Beijing. Hong ┼Änch'ung µ┤¬ÕĮźÕ┐Ā (1473ŌĆō1508) once praised the calligraphy of Yi Ch┼Ång µØĵŁŻ in

Cheij┼Ångmun ńźŁµØĵŁŻµ¢ć, stating: ŌĆ£Without even soiling his sleeves, he vigorously and convincingly reproduced the

Yishanbei and the

Lanting xu.

14ŌĆØ Likewise, Kw┼Ån Munhae (1534ŌĆō1591) pointed out that the transmitted version of the

Yishanbei had lost much of its original authenticity.

15 Meanwhile, records pertaining to epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts begin to appear in literary collections from the seventeenth century onward. That is, from the seventeenth century, epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts began to be introduced in earnest. It may be said that

Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun Yi U and H┼Å Mok played significant roles in the dissemination and popularization of these rubbings.

Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun Yi U was the culminating figure in the cultural achievements of seventeenth-century royal relatives of S┼Ånjo, building on the tradition of calligraphy and painting collection and artistic sensibilities passed down from Ich┼Ånggun ńŠ®µśīÕÉø (1428ŌĆō1460), Ins┼Ånggun õ╗üÕ¤ÄÕÉø (1588ŌĆō1628), and Inh┼Ånggun õ╗üĶłłÕÉø (1604ŌĆō1651). Drawing on the scholarly and artistic influence of his father Inh┼Ånggun, his three envoys to Beijing, and his association with the great scholar H┼Å Mok, he earned renown as a collector and editor of calligraphic and pictorial works. His life illustrates how princes of S┼Ånjo families in the seventeenth century accepted and practiced new cultural trends introduced into Chos┼Ån.

16 Accounts referring to Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun emphasize his fame as a practitioner of calligraphy, highlighting that he not only authored many stele inscriptions and hanging plaques but also collected and studied historical epigraphic.

17 He organized rubbings of steles and compiled the epigraphic anthology

Taedong k┼Łms┼Åks┼Å Õż¦µØ▒ķćæń¤│µøĖ, and during his missions to Beijing, he purchased Chinese epigraphic compilations and conducted active philological research together with noted scholars such as H┼Å Mok.

Particularly during his 1663 envoy to Beijing, Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun and his party acquired numerous stele rubbings, including Wang XizhiŌĆÖs ńÄŗńŠ▓õ╣ŗ (303ŌĆō361)

Shiqiqtie ÕŹüõĖāÕĖ¢,

Shengjiaoxu Ķü¢µĢÖÕ║Å, and

Huangtingjing ķ╗āÕ║ŁńČō, as well as Huai SuŌĆÖs µćĘń┤Ā (737ŌĆō799)

Qianziwentie ÕŹāÕŁŚµ¢ćÕĖ¢. Among them, the

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ, said to have been carved during the Xia ÕżÅ dynasty, was introduced to Chos┼Ån for the first time.

18 This rare example of a stele in ancient script drew widespread attention and played a key role in igniting the enthusiasm for epigraphy and ancient script in late Chos┼Ån. H┼Å Mok found inspiration in the Chinese epigraphic compilations that Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun brought backŌĆöincluding the

ShenyubeiŌĆöand developed his own unique script style.

19 Later scholars continued to conduct philological research on the

Shenyubei.

A royal descendant, Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun traveled to China as an envoy after the Py┼Ångja horan and brought back the seventy-seven characters from the

Nanyue zhishu bei ÕŹŚÕČĮµ▓╗µ░┤ńóæ of the Xia dynasty. As characters in that era were created by modeling the shapes of objects, the script resembled forms such as dragons, snakes, and plants, making it a marvelous trace of antiquity and a genuine artifact of the Three Dynasties õĖēõ╗Ż. Moreover, Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun possessed the

Shiguwen by Shi Zhou ÕÅ▓ń▒Æ of the Western Zhou Ķź┐Õæ© and the

Yishanbei in small seal script by Qin ń¦” prime minister Li Si µØĵ¢» (280ŌĆō208 BCE). Such a collection could only be acquired by one with a profound love of calligraphy.

20

Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun and H┼Å Mok maintained similar positions in both artistic taste and scholarly interest, particularly sharing a strong enthusiasm for the ancient studies movement of their time. As is well known, H┼Å Mok championed the Xia ÕżÅ, Yin µ«Ę, and Zhou Õæ© dynasties of China as ideal eras and believed that both art and governance should find their direction within them. His collected writings,

Kiy┼Ån Ķ©śĶ©Ć, include multiple anecdotes about his interactions with Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun, such as H┼Å Mok writing colophons for epigraphic compilations in Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun's collection or Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun showing H┼Å Mok stele rubbings.

21

As seen above, H┼Å Mok expressed admiration for Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun's passion for calligraphy as he introduced the so-called Three Dynasties rubbingsŌĆöthe

Shenyubei,

Shiguwen, and

Yishanbei, representing Xia ÕżÅ, Zhou Õæ©, and Qin ń¦”. Enchanted by the archaic spirit embodied in the Chinese rubbings, H┼Å Mok pursued a return to ancient seal script, thereby challenging the elegant yet aristocratic aesthetics of early Chos┼Ån typified by the Songs┼Ålch'e µØŠķø¬ķ½ö and the superficial emulation of Wang XizhiŌĆÖs style dominant in the calligraphic world of late Chos┼Ån. As a result, he cultivated various ancient seal forms and developed a wholly original script style.

22

In other words, influenced by the scholarly and artistic legacy of his father Inh┼Ånggun, Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun in the seventeenth century not only collected and researched Korean epigraphic compilations but also brought Chinese epigraphic rubbings into Chos┼Ån, thereby creating the objective conditions for the later enthusiasm for epigraphy. H┼Å Mok, by restoring the Three Dynasties rubbings into ancient seal script, developed a new style and played a key role in reviving seal script in the calligraphic world of late Chos┼Ån.

Furthermore, another contemporary, Kim Such┼Łng ķćæÕŻĮÕó× (1624ŌĆō1701), who excelled in seal script and reached the realm of Exquisite Subtlety ń▓ŠÕ”Ö, devoted himself to collecting Chinese epigraphic compilations and compiled the anthology K┼Łms┼ÅkchŌĆÖong ķćæń¤│ÕÅó. He also reprinted the Yishanbei, which had been introduced to Chos┼Ån, contributing significantly to the spread of seal script rubbings ń»åµøĖńóæÕĖ¢. Song Siy┼Ål Õ«ŗµÖéńāł (1607ŌĆō1689), a leading figure of the Noron faction, also showed considerable interest in the newly introduced epigraphic rubbings in ancient script. Thus, seventeenth-century Chos┼Ån literati, regardless of political faction, actively engaged with imported Chinese rubbings in ancient script, laying the social foundation for the rise of great collectors of Chinese epigraphic compilations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Philological Decipherment of Epigraphic Rubbings of Ancient Texts

Before examining perceptions of epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts in late Chos┼Ån, it is necessary first to summarize the extant Colophons ķĪīĶĘŗ, Identifications ĶŁśµ¢ć, and Prefaces Õ║ŵ¢ć related to these rubbings

.

As seen in the table above, Chos┼Ån literati left over twenty-one piecesŌĆöcolophons, identifications, and prefacesŌĆöconcerning epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts. Before the eighteenth century, they primarily commented on the Shiguwen, Shenyubei, and Yishanbei. It appears that Chos┼Ån literati maintained sustained interest in these so-called Xia, Zhou, and Qin ancient script rubbings (with seven colophons on the Shenyubei, eight on the Shiguwen, and seven on the Yishanbei). Therefore, the present study analyzes primarily the colophons on the Shiguwen, Shenyubei, and Yishanbei, in order to examine how Chos┼Ån literati perceived these works from a philological perspective.

As noted above, literati of Korea were already familiar with the stones drums ń¤│ķ╝ō through literary records and poetic writings dating back to the Kory┼Å period. The stones drums, which Kang Youwei Õ║ʵ£ēńł▓ (1858ŌĆō1927) referred to as the Zhonghua Diyiguwu õĖŁĶÅ»ń¼¼õĖĆÕÅżńē® ŌĆ£First Antiquity of ChinaŌĆØ, were unearthed in 627 in Chencangshan ķÖ│ÕĆēÕ▒▒, located in Fengxiangfu ķ││ń┐öÕ║£, and were therefore sometimes referred to as the Chencang Stone Drums ķÖ│ÕĆēń¤│ķ╝ō. In 1052, Xiang Zhuanshi ÕÉæÕé│ÕĖ½ acquired one of the drums from among the people and, in 1108, transferred it from Jingzhao õ║¼Õģå to Bianjing µ▒┤õ║¼. In 1127, Jurchens Õź│ń£× placed it in the residence of Wang Xuanwu µ▒¬Õ«ŻµŁ”, and it was later moved to the Daxing fuxue Õż¦ĶłłÕ║£ÕŁĖ.

During the Yuan dynasty, when Yu Ji ĶÖ×ķøå (1272ŌĆō1348) was serving as a professor at the Dadu Jiaoshou Õż¦ķāĮµĢĵij, the drums were again excavated from the mud and placed in front of the Dachengmen Õż¦µłÉķ¢Ć of the Guoxue Õ£ŗÕŁĖ. In 1339, Pan Di µĮśĶ┐¬ carved an annotated version (Yinxunwen ķ¤│Ķ©ōµ¢ć) of the text onto stone, erecting an Annotated SteleŌĆØ ķ¤│Ķ©ōńóæ beside the stones drums. In 1790, the Emperor Qianlong õ╣ŠķÜå (1736ŌĆō1795) of the Qing dynasty had replicas made of the stones drums and arranged them alongside the originals in front of the Dachengmen.

23 From 1339 to 1790, drums 1 through 5 were placed on the east side of the Dachengmen, while drums 6 through 10 and the annotated stele were located on the west side. In 1790, a railing was installed outside the building to protect the original drums, and the replicas were placed alongside them.

The complete set of Stone Drums consists of ten individual stones, each inscribed with the

Shiguwen text. These texts record episodes related to fishing and hunting. Each drum is named after the first two characters of the text it bears: Wuche ÕÉŠĶ╗Ŗ, Qianyi µ▒¦µ«╣, Tianche ńö░Ķ╗Ŗ, Luanshe ķæŠĶ╗Ŗ, Lingyu ķ£Øķø©, Zuoyuan õĮ£ÕĤ, Ershi ĶĆīÕĖ½, Majian ķ”¼Ķ¢”, Wushui ÕÉŠµ░┤, and Wuren ÕÉ│õ║║

.

The Shiguwen, ChinaŌĆÖs earliest known stone-inscribed poetic text, attracted the attention of many scholars beginning in the Ming and Qing periods. In the case of Chos┼Ån, judging from the writings of Kim Sish┼Łp, rubbings of the Shiguwen appear to have been introduced as early as the fifteenth century. During envoys to Beijing from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, Chos┼Ån envoys either made direct impressions of the ShiguwenŌĆÖs script or purchased rubbings, resulting in their substantial importation. In other words, while knowledge of the stones drums was widespread in the late Kory┼Å period through epigraphic texts and works such as Han YuŌĆÖs Shigu ge ń¤│ķ╝ōµŁī, in the late Chos┼Ån period this abstract understanding became materially concrete through envoy encounters.

ŌĆ£At the Temple Gate Õ╗¤ķ¢Ć, ten stone drums were lined up in two rows, five on each side. After passing through the Dong Wu µØ▒Õ╗Ī and Xi Wu Ķź┐Õ╗Ī, we entered the Temple Gate and finally viewed the so-called stone drums, which were said to be from the reign of King Xuan. The surface of the stone was fractured and eroded, and the text was barely distinguishable. The script was Zhouwen ń▒Ƶ¢ć, and its form resembled modern seal script, making it difficult to decipher. The phrase, ŌĆśThe coral branches intertwine, and the limbs of trees bend thickly, like dragons and serpents darting about,ŌĆÖ was no exaggeration. ... We touched them with our hands and sighed, as if witnessing with our own eyes the grand ritual of a royal hunt held long ago at Mount Qi Õ▓ÉÕ▒▒. We were overwhelmed by an ineffable sense of awe from across the ages.ŌĆØ

24

H┼Å Pong Ķ©▒ń»ł (1551ŌĆō1588), who served as S┼Ångj┼Ålsa Ķü¢ń»ĆõĮ┐ŌĆÖs S┼Åjanggwan, visited the Ming capital in 1574 and toured both the Guozijian Õ£ŗÕŁÉńøŻ and the stones drums. According to his record, all ten drums were preserved, five standing on each side of the Temple of the Former Master ÕģłÕĖ½Õ╗¤. The script on the drums was zhouwen. Han Yu had long ago described the visual effect of the Shiguwen in his Shigu ge, writing:

ŌĆ£How could they escape erosion over long years? With sharp blades they were carved like living dragons and crocodiles. Phoenixes soared and immortals descended; coral and jade-wood branches entangled each other.ŌĆØ

25 Hŏ Pong also quoted these lines to convey the power and beauty of the

Shiguwen. While most scholars limited themselves to textual criticism or structural assessment of strokes and composition, Hŏ Pong went beyond this by touching the drums himself and expressing a deeply emotional response.

Pak Chiw┼Ån µ£┤ĶČŠµ║É (1737ŌĆō1805), too, during his 1780 envoy, visited historical sites such as the Shuntian Fuxue ķĀåÕż®Õ║£ÕŁĖ, the Wen Tianxiangci µ¢ćÕż®ńźźńźĀ, and the Taixue Õż¬ÕŁĖ, and wrote that none compared to the stones drums in significance. For Pak Chiw┼Ån, however, the value of the stones drums was not solely historical or cultural. At the age of eighteen, he first encountered Han YuŌĆÖs

Shigu ge and was captivated by its extraordinary prose. Yet he deeply regretted not having seen the full text of the stone drums himself. To such a person, the opportunity to touch the stones drums and read Pan DiŌĆÖs annotated stele in person was an exceptional stroke of fortune.

26

However, taken as a whole, the literati of Chosŏn were less concerned with simply appreciating the aesthetic qualities of the stones drums than with deciphering the Shiguwen from a philological perspective.

Originally, the drums were found in the fields of Chencang and moved by Zheng Yuqing ķäŁķżśµģČ (746ŌĆō821) of the Tang dynasty to the Confucius Shrine in Fengxiang xian ķ││ń┐öńĖŻ, during which time one of the ten drums was lost. In the fourth year of the Huangyou ńÜćńźÉ (1052) of the Song dynasty, Xiang Zhuanshi ÕÉæÕé│ÕĖ½ recovered one from the public, thus completing the set of ten. In the second year of the Daguan Õż¦Ķ¦Ć (1108), the drums were moved from Jingzhao õ║¼Õģå to Bianjing µ▒┤õ║¼, first placed in the Biyong ĶŠ¤ķøŹ, and later transferred to the Baohuadian õ┐ØÕÆīµ«┐, where the characters were filled with gold. In the second year of the Jingkang ķØ¢Õ║Ę (1127), the Jurchens took the drums to Yanjing, removed the gold, and stored them in the home of Wang Xuanwu before transferring them to the Daxing fuxue . In the eleventh year of the Dade Õż¦ÕŠĘ (1307) under the Yuan dynasty, Yu Ji, then a professor at Dadu Õż¦ķāĮ, found the drums buried in mud.

27

Yu Ji recorded the following during the Dade era of the Yuan: "Zheng Yuqing of the Tang first discovered them in the fields of Chencang and placed them in the Fengxiang fuxue. During the Song's Daguan period, they were moved to the Taixue of Bianjing, where the characters were filled with gold. At the end of the Jingkang era, the Jin people took them to Yan and removed the gold. They were brought here during Yu Ji's time."

28

The stones drums are approximately two chŌĆÖ┼Åk Õ░║ in height and slightly over one chŌĆÖ┼Åk in diameter. There are ten drums in total, shaped like barrel drums with domed tops. Around each drum is inscribed a hunting poem attributed to King Xuan, using seal characters by Shi Zhou. In ancient times, the drums were located in the fields of Chencang, with only eight surviving. They were moved by Zheng Yuqing to the Confucius Temple in Fengxiang; then, during the Huangyou reign of Emperor Renzong õ╗üÕ«Ś (1022ŌĆō1063) of the Song, Xiang Fushi found the remaining two among the people, thereby completing the set. Emperor Huizong ÕŠĮÕ«Ś (1082ŌĆō1135) moved them to the Biyong and filled the inscriptions with melted gold, later placing them in the Baohuadian. During the Jingkang Incident ķØ¢Õ║Ęõ╣ŗĶ«Ŗ, the Jin took them to Yanjing and scraped off he gold. In the Yuan dynastyŌĆÖs Huangqing ńÜćµģČ (1312ŌĆō1314), Yu Ji, then serving as a professor at Dadu, placed them within the gate of the Confucian temple.

29

According to records from Y┼Ånhaengnok ńćĢĶĪīķīä, Chos┼Ån literati who visited Yanjing in the late Chos┼Ån period and viewed the stones drums did more than describe their physical features and conditionŌĆöthey also traced their transmission and demonstrated a generalized philological awareness. Moreover, their records of the drums' transmission often appear remarkably similar. This phenomenon can be explained in two ways: first, Chos┼Ån literati regularly consulted their predecessors' writings when composing their own envoy journals, making some repetition inevitable; second, they frequently cited content directly from widely circulated works among diplomatic envoys, such as the Daxing xianzhi Õż¦ĶłłńĖŻÕ┐Ś and the Dijing jingwu l├╝e ÕĖØõ║¼µÖ»ńē®ńĢź, naturally resulting in high textual overlap.

Traditionally, it was said that these drums were hunting steles carved under King Xuan of Zhou, with the inscriptions praising the Son of HeavenŌĆÖs hunts and the calligraphy attributed to the Grand Historian Shi Zhou Õż¬ÕÅ▓ ÕÅ▓ń▒Ć. In Jiang ShiŌĆÖs µ▒¤Õ╝Å Lunshu biao Ķ½¢µøĖĶĪ©, it is written: ŌĆ£Shi Zhou authored fifteen chapters of large seal script, which was similar to yet distinct from the ancient script of Cang Jie ÕĆēķĀĪ. People of the time called it Zhoushu ń▒Ģ, also known as ŌĆśShiŌĆÖs scriptŌĆÖ ÕÅ▓µøĖ.ŌĆØ In Zhang HuaiguanŌĆÖs Õ╝ĄµćĘńōś Shu duan µøĖµ¢Ę, it is said: ŌĆ£Zhouwen ń▒Ģµ¢ć was created by the Grand Historian of Zhou, and its form is preserved in the Shiguwen.ŌĆØ

In the Pukchae birok ÕŠ®ķĮŗńóæķīä, we find: ŌĆ£The stones drums were originally located in the fields of Chencang, and during the Tang dynasty, Zheng Yuqing moved them to the Confucius temple in Fengxiang. They were later lost during the wars of the Five Dynasties. Sima Chi ÕÅĖķ”¼µ▒Ā (980ŌĆō1041) of the Northern Song reinstalled them at the Fengxiang fuxue, but one was missing. During the Huangyou reign, Xiang Fushi recovered it. In the Daguan era, they were transferred to Bianjing and placed in the Baohuadian. During the Jingkang Incident ķØ¢Õ║Ęõ╣ŗĶ«Ŗ, their whereabouts were again lost.ŌĆØ

Daxing xianzhi records: ŌĆ£In the second year of Jingkang, the Jin took them to Yanjing, removed the gold, and placed them in the Daxing fuxue. In the eleventh year of the YuanŌĆÖs Dade era, Yu Ji found them in a field and first moved them to the Guoxue Õ£ŗÕŁĖ.ŌĆØ They survived through the Ming and remain preserved today. During the Qin, Han, Wei, and Jin periods, the drums were virtually unknown. Not until the Later Zhou ÕŠīÕæ© did Su Xu ĶśćÕŗ¢ first record them. In the early Tang, Yu Shinan ĶÖ×õĖ¢ÕŹŚ (558ŌĆō638), Chu Suiliang ĶżÜķüéĶē» (597ŌĆō658), and Ouyang Xun µŁÉķÖĮĶ®ó (557ŌĆō641) all praised their exquisite brushwork. Wei Suzhou ķ¤ŗĶśćÕĘ× (737ŌĆō792), Han Changli ķ¤ōµśīķ╗Ä (768ŌĆō842), and Su Zizhan ĶśćÕŁÉń×╗ (1037ŌĆō1101) composed rhapsodies in their honor. Huang Shangu ķ╗āÕ▒▒Ķ░Ę (1045ŌĆō1105) remarked that their calligraphy had the transcendence of jade tablets ńŬńÆŗ and could not have been forged by later generations. Thus, lovers of antiquity always held the stones drums in the highest esteem. The

Yishanbei and the

Zuchuwen Ķ®øµźÜµ¢ć were likewise considered astral remnants of XiŌĆÖe ńŠ▓Õ©ź. Later scholars such as Zheng Qiao ķ䣵©Ą (1104ŌĆō1162), Shi Su µ¢ĮÕ«┐, Xue Shangong Ķ¢øÕ░ÖÕŖ¤, Wang Houzhi, and Pan Di corrected errors, provided phonetic annotations, and conducted philological studies that led the

Shiguwen to become widely known throughout the world.

30

Concerning the

Shiguwen, unlike other Chos┼Ån literati who either copied previous records verbatim or directly cited the originals, I Kichi µØÄÕÖ©õ╣ŗ (1690ŌĆō1722) synthesized chronological documentation of the stones drums and meticulously traced their transmission history. In the preface of epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ń¤│ķ╝ōÕĖ¢Õ║Å, Yi cited such works as

Lunshubiao Ķ½¢µøĖĶĪ©

31 by Jiang Shi µ▒¤Õ╝Å,

Shuanduan µøĖµ¢Ę by Zhang Huai'guan Õ╝ĄµćĘńōś,

Fuzhaibilu ÕŠ®ķĮŗńóæķīä by Wang Houzhi ńÄŗÕÄÜõ╣ŗ, and

Daxing xianzhi Õż¦ĶłłńĖŻÕ┐Ś. Through these sources, he examined the evolution of scholarly perception of the stones drums among scholars from the Southern and Northern Dynasties to the Tang and Southern Song periods, while also verifying the epigraphic nature and transmission of the texts. All of these sourcesŌĆöincluding

Lunshubiao,

Shuanduan,

Fuzhaibilu, and Huang TingjianŌĆÖs commentaryŌĆöare recorded in the

Rixiayouwenkao µŚźõĖŗĶłŖĶü×ĶĆā, from which it may be inferred that Yi relied primarily on this work for tracing the history of the

Shiguwen. Yet Yi did not indiscriminately transcribe all textual data; instead, he selectively extracted representative materials from among many sources. This allowed for a systematic reconstruction of the transmission process and a chronological examination of the shifts in perception regarding the stones drums. Moreover, the preface of epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts demonstrates that Chos┼Ån literati did not rely solely on specialized treatises on epigraphy ķćæń¤│ÕŁĖ but also actively engaged with encyclopedic compendia such as

Rixiayouwenkao and

Didu jingwul├╝e ÕĖØķāĮµÖ»ńē®ńĢź.

Chosŏn literati not only incorporated such transmission records but also applied textual criticism to the contents and structure of the

Shiguwen. Sŏ Yuku, for instance, questioned a phrase in the version of the

Shiguwen amplified by Yang Shen µźŖµģÄ (1488ŌĆō1559)ŌĆöspecifically, the line ŌĆ£I came from the EastŌĆØŌĆöarguing that it conflicted with the actual geography of Qiyang Õ▓ÉķÖĮ and Haojing ķļõ║¼. He further criticized Yang for forcibly expanding the text by adding a character to each line.

32 Most notably, S┼Å challenged the established claim that Li Dongyang µØĵØ▒ķÖĮ (1447ŌĆō1516) had transmitted the contemporary rubbing of the

Shiguwen to Yang.

As for the

Shenyubei, the original stele was located on the Nanyue ÕŹŚÕČĮ range of Hengshan ĶĪĪÕ▒▒, though the original no longer survives. A recarved version now stands at the northern peak of Yuelushan ÕČĮķ║ōÕ▒▒. Composed in tadpole script ĶØīĶܬµ¢ć, it contains 77 characters celebrating Yu the GreatŌĆÖs flood-control achievements

.

Liu Xian ÕŖēķĪ» of the Liang dynasty documented in the Cuijilu ń▓╣µ®¤ķīä the discovery of the

Shenyubei: a recluse named Cheng Yi µłÉń┐│ encountered the stele while wandering Hengyue ĶĪĪÕČĮ. When he submitted a copy to the king, it was considered a national treasure, and a proper stone was chosen for recarving. From then on, the

Shenyubei came into public knowledge.

33 Nanyue was also called Gouloushan Õ▓ŻÕČüÕ▒▒, and during the Wei-Jin to Sui-Tang periods, these names were often interchangeable. Thus, the

Shenyubei was also known as the

Gouloubei Õ▓ŻÕČüńóæ. From the Southern Qi period of the Southern Dynasties onward, the

Shenyubei gradually came to light. Han Yu ķ¤ōµäł of the Tang dynasty once journeyed to Gouloushan in search of the stele but failed to locate it, later composing the poem

Gouloushan Õ▓ŻÕČüÕ▒▒. Likewise, Liu Yuxi ÕŖēń”╣ķī½ (772ŌĆō842) wrote of the stele in his literary works, while Zhang Shi Õ╝ĄµĀ╗ (1133ŌĆō1180) and Zhu Xi µ£▒ńå╣ (1130ŌĆō1200) also sought the stele in vain, casting doubt on its very existence.

34 During the Jiajing ÕśēķØ¢ (1521ŌĆō1567) of the Ming dynasty, the

Shenyubei at Yuelushan resurfaced. Scholars immediately turned their attention to the stele, seeking to authenticate it and interpret its inscriptions. Yang Shen was the first to attempt a decipherment, followed by Shen Yi µ▓łķÄ░ (1025ŌĆō1067) and Yang Shih-chŌĆÖiao µźŖµÖéÕ¢¼ (1531ŌĆō1609), who also engaged in interpretive work.

The time at which the

Shenyu bei was introduced into Chosŏn is not documented in historical sources. However, considering that this stele became widely known beginning in the Ming dynasty and began to draw serious scholarly attention from that period, it can be inferred that rubbings of the stele were likely introduced into Chosŏn during the sixteenth or seventeenth century. According to extant records, the earliest known individual to have encountered the

Shenyu bei may have been Yun Hyu Õ░╣ķæ┤ (1617ŌĆō1680).

35 In Yun HyuŌĆÖs collected writings,

Paekhojip ńÖĮµ╣¢ķøå, there appears a poem titled

Chagubiga hyohanmun'gong s┼Åkkogach'e õĮ£ń”╣ńóæµŁī µĢłķ¤ōµ¢ćÕģ¼ń¤│ńÜʵŁīķ½ö, which was composed in 1659 when Yun Hyu happened upon a rubbing of the

Shenyu bei and was inspired to write verse.

Who was it that brought this rubbing to our eastern land?

I was both delighted and astonished upon receiving it.

Seventy-seven characters, like writhing dragons and horned serpents,

Soaring and leapingŌĆösuspended as if among the stars of Ji and Di.

Could it be the very turtle that emerged from the Luo River bearing the charts of divination?

Or the dark jade tablet unearthed from a tomb long hidden?

Ķ¬░Õ░ćµŗōµ£¼µĄüµØ▒Õ£¤

µłæµ│üÕŠŚõ╣ŗµ¼Żõ╗źķ¦Ł

õĖāÕŹüõĖāÕŁŚķŠŹĶףĶÖ»

ķŠŹķ©░µŁ”Ķ║ŹµćĖń«Ģµ░É

õĖĆõ╝╝ķŠ£ń¢ćÕć║µĘĖµ┤ø

Yun Hyu first elaborated through verse upon historical anecdotes: Yao ÕĀ» became an emperor; Yi ńŠ┐ defeated fierce beasts; and when the great flood broke out, Yu ń”╣ controlled the waters. Then he proceeded to describe Shenyubei, which records the achievements of YuŌĆÖs water management. As seen in the poem, Yun Hyu, upon acquiring a rubbing of Shenyubei in 1659, was astonished by characters shaped like Ch'iryong ĶףķŠŹ, Kyuryong ĶÖ»ķŠŹ. Upon viewing these characters, he was reminded of the nine principles carved on the patterned shell of the divine turtle that emerged from the Luo River µ┤øµ░┤, and of the mysterious jade disk excavated from ancient tombs. Rather than decoding Shenyubei from a philological standpoint, Yun Hyu expressed his antiquarian interests and his admiration for the artifact through poetry. Most significantly, the poem confirms that a rubbing of Shenyubei had already been introduced to Chos┼Ån by 1659.

The earliest known account of how

Shenyubei was brought to Chosŏn appears in the

Nangs┼Ån'gun kyemyo y┼Ånhaengnok µ£ŚÕ¢äÕÉøńÖĖÕŹ»ńćĢĶĪīķīä by Yi U. As previously discussed, Yi U was fond of literary and pictorial works and took every opportunity during diplomatic envoys to acquire the writings and artworks of ancient masters. During his third envoy to Beijing in 1663, he reportedly purchased two copies of

Guzhuan Shenyubei ÕÅżń»åńź×ń”╣ńóæ from Wang Yi ńÄŗµĆĪ in the Fengrun Ķ▒ɵĮż region.

37 Upon returning to Chosŏn with the rubbings, Yi U sought to decipher the inscriptions and thus sent the rubbings to Hŏ Mok, a contemporary scholar of ancient script studies.

On the fifteenth day of January, it snowed heavily again. While I was staying at Hengshan µ®½Õ▒▒, Lord Nangs┼Ån (Yi U) returned from his diplomatic mission and sent me the

Shenyubei from Hengshan. The script was extremely peculiarŌĆöunlike bird-track or ancient script styles. Apocryphal histories say that the Xia sovereign devised a script resembling seal script, and this must be it. Compared to

Shiguwen, it is even more archaic and difficult to interpret. The sage lived over 3,700 years ago, and the stele had long disappeared from the world. It was unearthed from the earth of Hengshan during the Ming Jiajing ÕśēķØ¢. The Minister of Rites, Zhan Ruoshui µ╣øĶŗźµ░┤ (1466ŌĆō1560), appended an explanatory postscript to the inscription.

38

Hŏ Mok recorded these impressions on January 15, 1664, upon receiving a rubbing of

Shenyubei from Yi U. He wrote: "The characters are exceedingly peculiar and differ from bird-track and ancient script styles. It must be what the Xia sovereign devised as resembling seal script." His letter also reveals the provenance of the rubbing. According to his note, Zhan Ruoshui added a commentary on the reverse side of the rubbing, confirming that the copy was of the stele erected at Ganquan shuyuan ńöśµ│ēµøĖķÖó. The copy of

Shenyubei acquired by Yi U was thus a rubbing of the stele established at Ganquan shuyuan during the Ming Jiajing, with Zhan RuoshuiŌĆÖs postscript,

Shuganquan zishan shuyuan fanke Shenyubei hou µøĖńöśµ│ēÕŁÉÕ▒▒µøĖķÖóń┐╗Õł╗ńź×ń”╣ńóæÕŠī, affixed to the reverse.

39

The year after this old man returned from the East Sea, the royal descendant Lord Nangs┼Ån sent me the Shenyubei from Hengshan . The script seems to imitate the harmonies of heaven and earthŌĆölike birds soaring high, beasts darting swiftly, dragons ascending to the heavens, and tigers moving with ferocity. It gleams resplendently with sacred and auspicious forms that no brush could imitate. It does not resemble the script of Fu Xi õ╝ÅńŠ▓ or the Huangdi ķ╗āÕĖØ.

Ancient records state that the Xia sovereign devised the character that resembles zhuan ń»å. During the height of the flood, when humans, animals, and spirits intermingled chaotically, King Yu broke through mountains to channel the waters into the sea and carved out the Nine Provinces. He marked the high mountains and great rivers, casting bronze tripods with monstrous images to reveal dangerous creatures. Observing these, people could avoid threats and live peacefully. At that time, he received the auspicious Luo River writing and expounded the Nine Principles of Hongfan jiuchou µ┤¬ń»äõ╣Øń¢ć. Transforming the scripts of bird-tracks and Jiahua Õśēń”Š, he inscribed them onto a stele erected at HengshanŌĆöthis too was a pictographic writingŌĆ” The Xia sovereign, upon taming the waters and lands, created these characters based on pictorial forms. These script forms are strange yet upright and majestic without being disorderly. The

Shiji ÕÅ▓Ķ©ś says: ŌĆ£King YuŌĆÖs body was the standard; his voice, the pitch; his left hand, the compass; his right hand, the square.ŌĆØ His script too embodies compass and square.

40

The philological achievement of

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ by H┼Å Mok can be confirmed through this postscript. First, he characterized the script of

Shenyubei using metaphorical language, describing it as resembling birds soaring high, wild beasts darting swiftly, dragons ascending into the sky, and tigers transforming in motion. He then developed a reasoned argument based on existing theories about

Shenyubei and the chapters

Yugong ń”╣Ķ▓ó and Hongfan µ┤¬ń»ä in the Shujing µøĖńČō.

41 As was commonly accepted by earlier scholars,

42 Hŏ Mok also argued that

Shenyubei was associated with the ancient tale of Great Yu's flood control. He elaborated on Yu's merits by referring to records in

Yugong of the Shujing and in the

Zuo zhuan ÕĘ”Õé│, explaining the historical context in which

Shenyubei was erected. Although the relationship between

Shenyubei and

Yugong is explicitly noted in the postscript by Zhan Ruoshui, the connection between the construction of

Shenyubei and the tradition in the Xia dynasty of casting great tripods and engraving various shaped objects had not previously been clarified. According to the third year of Duke Xuan in the

Zuo zhuan, ŌĆ£In ancient times, when the virtue of the Xia dynasty flourished, distant regions were ordered to draw the forms of their peculiar things and to contribute metal to the nine provinces. Great tripods were cast, and various forms of things were engraved on them, so that the forms of all things would be contained therein, enabling the people to discern the divine from the deceitful. Hence, the people could enter rivers, lakes, mountains, and forests without encountering misfortune, and demons and monsters could not harm themŌĆØ.

This confirms that, as early as the Xia dynasty, information was conveyed to the people through the method of modeling things. In light of this precedent, it is possible that Yu also inscribed characters on a stele in the form of modeled things to disseminate information or record events. Subsequently, H┼Å Mok, based on the record from the Hongfan chapter of the ShujingŌĆöŌĆ£Heaven bestowed upon Yu the Hongfan with its Nine CategoriesŌĆØŌĆöconcluded that Shenyubei had been engraved by Yu in the form of modeled things after he had subdued the flood, by adapting the Bird-trace script ķ│źĶĘĪµøĖ and Jiahe script Õśēń”ŠµøĖ to inscribe the Hongfan he had received from Heaven.

Moreover, Hŏ Mok evaluated the aesthetic value of Shenyubei, asserting that its calligraphy was unusual, upright, and solemn, yet not disordered. Although he could not fully assess the authenticity of Shenyubei due to the limitations of his era, what is most significant is that he systematically verified the inscription by referencing the canonical records of the Shujing, Zuo zhuan, and prior scholarly theories, and articulated his own original viewpoint.

By the eighteenth century, with the influx of epigraphy studies, certain Chosŏn scholars began to question the authenticity of

Shenyubei, which had previously been widely revered as the progenitor of

archaic script. Nam K┼Łkkwan, for example, believed that late Song scholars had fabricated

Shenyubei based on poems by Han Yu and Liu Yuxi. He also criticized the characters for appearing unnaturally twisted and bulging, thereby devaluing

Shenyubei as of little worth.

43 Although Nam K┼Łkkwan did not undertake a comprehensive philological verification of

Shenyubei, what is especially notable is that, within the social context of Chosŏn where

Shenyubei was generally venerated as the origin of

archaic script, he independently raised questions about its authenticity and linguistic value. Furthermore, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng µłÉµĄĘµćē (1760ŌĆō1839) cited the theories of Yang Shen and Gu Yanwu and discussed the origin, editions, and authenticity of

Shenyubei from a philological perspective.

Yang Shen wrote, ŌĆ£Numerous renowned figures throughout history have praised and recorded the

Shenyubei of Hengshan. However, Liu Yuxi and Han Changli never saw it, and even Zhu Xi and Zhang Shi, who traveled to Nanyue, failed to locate it. In

Yudi jisheng Ķ╝┐Õ£░ń┤ĆÕŗØ by Wang Xiangzhi, it is written: ŌĆśThe stele is located at Gouloufeng Õ▓ŻÕČüÕ│». Some say it lies at Yunmifeng ķø▓Õ»åÕ│». In the past, a woodcutter saw it, and during the Jiading ÕśēÕ«Ü of the Song dynasty, a scholar from Shu Ķ£Ć, guided by the woodcutter, reached the site and produced a rubbing of about seventy characters, which he engraved within Kuimen Õżöķ¢Ć. However, the stele later disappeared. More recently, Jiwen ÕŁŻµ¢ć and Zhang Qianxian Õ╝ĄÕāēµå▓ obtained a copy in Changsha ķĢʵ▓Ö and identified it as the one that He Zhi õĮĢĶć┤ had reproduced once at Yuelu Shuyuan ÕČĮķ║ōµøĖķÖó during the Song Jiading.ŌĆÖ Gu Yanwu stated: ŌĆśBefore Han Tuizhi, no one had seen this stele. It was first discovered and reproduced by He Zhi at the foot of Zhuyongfeng ńźØĶ׏Õ│». When the magistrate of Hengshan later searched for it, the site had already been lost. The current so-called Yubei ń”╣ńóæ has characters that are mysterious but lack proper form, language that is novel but lacks coherence, and rhymes that are strange yet do not conform to antiquity. This is enough to prove that it is a forgery.ŌĆÖŌĆØ Based on these two views, it is evident that the

Shenyubei transmitted today is a reproduction created by He Zhi. Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun, that is, Yi U, once acquired a copy of it during his journey to Beijing. The inscription included phrases such as ŌĆ£S┼Łngjewalch'a, Ikpojwagy┼ÅngŌĆØ µē┐ÕĖصø░ÕŚ¤, ń┐╝Ķ╝öõĮÉÕŹ┐, which clearly contradict the historical sequence outlined by Gu Tinglin ķĪ¦õ║Łµ×Ś. Could the title Ky┼Ång ÕŹ┐ have existed during the Tang ÕöÉ or Yu ĶÖ× periods? One may infer much from this inconsistency.

44

While Nam K┼Łkkwan judged the authenticity of the

Shenyubei somewhat rashly and subjectively, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng approached the matter with scholarly rigor, building upon prior research and assessing the steleŌĆÖs authenticity with objectivity. S┼Ång Hae┼Łng primarily cited

Danyanlu õĖ╣ķēøķīä by Yang Shen and

Jinshiwenziji ķćæń¤│µ¢ćÕŁŚĶ©ś by Gu Yanwu. Yang Shen, a renowned Ming-dynasty writer, was celebrated not only for his literary output and vast erudition, but also for his achievements in textual criticism, philology, and epigraphy. Notably, he was the first to interpret the

Shenyubei from an epigraphic perspective, producing a detailed commentary on the inscription and composing a 700-character poem, Yubeige ń”╣ńóæµŁī, in praise of YuŌĆÖs accomplishments and as a vehicle for expressing his literary insights. He also made great efforts to disseminate knowledge of the stele by establishing engraved copies across the Yunnan ķø▓ÕŹŚ area.

45 Thus, Yang Shen may rightly be considered both the pioneer in interpreting the

Shenyubei and a key figure in promoting its legacy.

S┼Ång Hae┼Łng quoted from Danyanlu zonglu õĖ╣ķēøķīäńĖĮķīä to present various theories regarding the transmission of the Shenyubei, explaining how its precise location and transmission history remained unclear. He then cited the findings of Gu Yanwu, who stated that during the Northern Song Jiading ÕśēÕ«Ü, He Zhi first discovered and transmitted the stele from beneath Zhuyongfeng. This allowed S┼Ång Hae┼Łng to clarify both the circumstances surrounding the steleŌĆÖs discovery and the provenance of the extant version. Finally, drawing upon the philological conclusions of Yang Shen and Gu Yanwu, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng presented his own interpretation. He concluded that the existing copies of the Shenyubei were all based on He ZhiŌĆÖs initial reproduction, and that the version brought to Chos┼Ån by Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun was one of these.

Moreover, as cited above, Gu Yanwu once criticized the

Shenyubei, stating that ŌĆ£Its words are bizarre and do not conform to reasonŌĆØ. S┼Ång Hae┼Łng, while accepting Gu Yanwu's argument, based his reasoning on the commentary by Yang Shen. In Yang Shen's interpretation of the

Shenyubei, the phrase ŌĆ£S┼Łngjewalch'a, Ikpojwagy┼ÅngŌĆØ µē┐ÕĖصø░ÕŚ¤, ń┐╝Ķ╝öõĮÉÕŹ┐

46 appears. The term Ky┼Ång ÕŹ┐ did not begin to refer to government officials until the Qin and Han periods.

47 Thus, the use of ky┼Ång in a stele purportedly established by Xia Yu ń¦”ń”╣ constitutes clear evidence that the

ShenyubeiŌĆÖs language lacks coherence and that the inscription is a forgery. Notably, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng did not merely accept the findings of Yang Shen and Gu Yanwu passively. Instead, he verified specific phrases in the

Shenyubei from a philological standpoint, thereby providing a critical foundation for Gu YanwuŌĆÖs conclusion. By examining the inscriptionŌĆÖs transmission process, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng further substantiated which version had been introduced to Chos┼Ån and reasonably concluded that the extant

Shenyubei was indeed a forgery.

Furthermore, considering that both Yang ShenŌĆÖs and Gu YanwuŌĆÖs discourses appear verbatim in the section Xiayubei of the

Peiwenzhai shuhuapu õĮ®µ¢ćķĮŖµøĖńĢ½Ķ░▒, it is plausible that S┼Ång Hae┼Łng consulted this encyclopedic source directly rather than referencing

Danyanlu õĖ╣ķŹŠķīä and

Jinshiwenziji ķćæń¤│µ¢ćÕŁŚĶ©ś.

48 This also demonstrates that Chosŏn scholars, when conducting epigraphic research, often relied more on comprehensive encyclopedic compilations of theories than on single-issue treatises.

Meanwhile, as previously discussed, from the seventeenth century onward, antiquarian writers and calligraphers such as Hŏ Mok regarded the

Shenyubei as the progenitor of ancient script and praised its calligraphic beauty, actively embracing it. By the eighteenth century, Chosŏn scholars began to question its authenticity, adopting a more critical approach to its discovery, transmission, and versions. Some Chosŏn calligraphers also came to devalue the calligraphic worth of the

Shenyubei. Nam Kongch'┼Ål ÕŹŚÕģ¼Ķ╗ī (1760ŌĆō1840) pointed out that the stele's characters were grotesque and must have been forged, arguing that repeated reproductions had eroded the original appearance. He remarked that ŌĆ£To believe entirely in the Shujing is no better than having no Shujing at allŌĆØ.

49 Kang Sehuang Õ¦£õĖ¢µÖā (1713ŌĆō1791) went even further, scrutinizing the brushstrokes and line techniques. He examined the relationship between the seal script style, which had flourished in Chos┼Ån calligraphy at the time, and the

Shenyubei. He harshly criticized the impact of this forged stele on Chosŏn calligraphic practice, asserting that its introduction had led to clumsy and heavy-handed habits in the study of seal script.

ŌĆ£TodayŌĆÖs students of seal script write based solely on subjective judgmentŌĆöbrushstrokes go wherever they feel like, mixing regular and cursive strokes for convenience or rotting to popular tastes. Some deliberately craft bizarre or eccentric forms to deceive the ignorant and claim superiority. Such behavior is lamentable and beyond reproach.ŌĆØ

50

There are two general styles of seal script in our country, ancient and modern. One style begins its brushstrokes with slanted tip ÕüÅķŗÆ and deliberately employs war-like strokes µł░ńŁå. Each dot ķ╗× carries the energy of cursive script ĶŹēµøĖ, and the downward slant µÆć resembles that of standard script µźĘµøĖ. It was thought to have originated from

Shenyubei. But how can one be sure that

Shenyubei was not a later fabrication by descendants? Moreover, when people today arbitrarily fabricate ancient script characters with modern brushstrokes, forcing them into a lavishly fluid form, they fail to escape the vulgar and inferior aesthetic.

51

This criticism appears in the colophon by Kang Sehwang on the Chenghuangbei Õ¤ÄķÜŹńóæ by Li Yangbing µØÄķÖĮµ░Ę. Calligraphers of Chos┼Ån in the late period frequently practiced zhuanshu in two forms. One combined brush strokes from standard script and cursive script, producing grotesque and exaggerated forms based on what they believed to be the Shenyubei. However, the Shenyubei may in fact be a forgery by later hands. Arbitrarily creating ancient forms using modern brushwork only perpetuates vulgar convention.

The above content is drawn from a postscript composed by Kang Sehwang regarding the Chenghuangbei, a stele inscribed by the famed seal script master Li Yangbing. Before offering his critique of Li YangbingŌĆÖs seal script, Kang Sehwang first assessed the stylistic tendencies of seal script within the calligraphic circles of Chos┼Ån. According to him, two main trends in seal script prevailed in late Chos┼Ån: one arose out of convenience, blending the strokes of standard script and cursive script; the other deliberately adopted bizarre and ingenious forms. Among these, seal script was said to feature twisted and curved strokes, dots that embodied the energy of cursive script, and downward slanting strokes resembling those in standard scriptŌĆöall of which were believed to originate from the Shenyubei.

While the philological focus for the Shiguwen and Shenyubei centered on textual meaning, the Yishanbei debate revolved around authenticity. From its earliest circulation in Chos┼Ån, scholars appreciated its calligraphy and adopted its styleŌĆöbut continually questioned its genuineness and authorship. Though the stele arrived in the 15th century, it only garnered serious scholarly attention in the 17th centuryŌĆöspurred by Kim Such┼Łng ķćæÕŻĮÕó× (1624ŌĆō1701), who reproduced it by rubbing and carving. H┼Å Mok was the first Chos┼Ån scholar to recognize its artistic and academic value; Kim became the prime mover in its dissemination.

Kim Such┼Łng, whose courtesy name was Y┼Ån-ji Õ╗Čõ╣ŗ, was the eldest grandson of Munjeong-gong µ¢ćµŁŻÕģ¼ Kim Sang-heon ķćæÕ░Öµå▓ (1570ŌĆō1652). A devoted disciple of Song Siy┼Ål Õ«ŗµÖéńāł (1607ŌĆō1689), he was deeply learned and skilled in seal script, zhoushu, and eight-part script Õģ½Õłåķ½ö, and produced many inscriptions.

52 His engraved

Yishanbei is believed to be the only Chinese seal script textbook carved and published in Chosŏn. Thus, with the

Yishanbei reissued, Chosŏn scholars not only recognized its aesthetic merit but actively engaged in verifying and deciphering it using poems, epigraphic texts, and other historical materials.

Regarding the ŌĆ£Yishan SteleŌĆØŌĆöerected by Qin Shi Huang to commemorate his own achievementsŌĆöthe scholarly communities remained divided. Kang Sehuang suggested the lack of clear aesthetic standards in stroke form contributed to disagreements. He cited Ouyang Xiu, who wasnŌĆÖt reluctant to deem even parts of the Book of Changes as spurious. If Ouyang could doubt Yijing sections, how could one fully trust his comments on this stele? Kim Such┼Łng countered by engraving both sides of the discussion in the engraved edition, appending diverse opinions to aid future readers in comparative analysisŌĆöa fair and balanced approach.

53

As previously discussed, Kim Such┼Łng, who was deeply versed in seal script, was not only broadly learned but also was praised as being refined in character, free from even the slightest vulgarity. Thus, Song Siy┼Ål valued him highly, and the two maintained a teacher-friend relationship based on shared ideals. Kim Suj┼Łng, having early abandoned pursuit of the civil service examination, occasionally served as Surye┼Ång Õ«łõ╗ż of S┼Åks┼Ång-hy┼Ån ń¤│Õ¤ÄńĖŻ and P'y┼Ånggang hy┼Ån Õ╣│Õ║ĘńĖŻ, and established Ch┼Ångudang µĘ©ÕÅŗÕĀé, K┼Łnminh┼Ån ch'┼Ångs┼Ångdang Ķ┐æµ░æĶ╗ƵĘĖń£üÕĀé, K┼Łnmindang Ķ┐æµ░æÕĀé, and Sagwanj┼Ång ÕøøÕ»¼õ║Ł. Song Siy┼Ål composed commemorative inscriptions for all these places.

In addition, Song Siy┼Ål took great interest in Kim Such┼ŁngŌĆÖs calligraphy and painting and appears to have written an unusually large number of postfaces related to them. In the Songjadaej┼Ån Õ«ŗÕŁÉÕż¦Õģ©, eight postfaces are preserved that he wrote in response to KimŌĆÖs calligraphy, painting, and epigraphy albums, including Chunggak Y┼Åksanbibal ķćŹÕł╗ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæĶĘŗ, Chinj┼Ånch'┼Åpbal ń¦”ń»åÕĖ¢ĶĘŗ, Maew┼Åltang hwasangbal µóģµ£łÕĀéńĢ½ÕāÅĶĘŗ, Ch'wis┼Ångdobal Ķüܵś¤Õ£¢ĶĘŗ, S┼Å Kim Y┼Ånji s┼Åhu µøĖķćæÕ╗Čõ╣ŗµøĖÕŠī, S┼Å Kim Y┼Ånji bonghwa Munj┼Ång s┼Ånsaeng si hu µøĖķćæÕ╗Čõ╣ŗÕźēÕÆīµ¢ćµŁŻÕģłńö¤Ķ®®ÕŠī, K┼Łms┼Åkch'ongbal ķćæń¤│ÕÅóĶĘŗ, and K┼Łms┼Åkch'ongbal chaepal ķćæń¤│ÕÅóĶĘŗÕåŹĶĘŗ. Through these writings, the nature of their artistic exchanges can be discerned.

Among these, Chunggak Y┼Åksanbibal and Chinj┼Ånch'┼Åpbal are particularly noteworthy. In May 1672, Song Siy┼Ål composed a postface for the Yishanbei, which had been recopied by Kim Suj┼Łng, and especially praised KimŌĆÖs inclusion of scholarly findings concerning Yishanbei by scholars from successive dynasties at the end of the stele text.

Whereas it was common in Chos┼Ån for scholars to uncritically accept the epigraphic theories of Ouyang Xiu regarding Yishanbei, Kim Suj┼Łng refrained from such blind imitation. Instead, he cited not only the views of Ouyang Xiu but also those of epigraphers such as Zhao Mingcheng ĶČÖµśÄĶ¬Ā (1081ŌĆō1129) and Wang Shizhen ńÄŗõĖ¢Ķ▓× (1526ŌĆō1590), thereby demonstrating an independent critical attitude. Accordingly, Song Siy┼Ål also remarked that Ouyang XiuŌĆÖs opinion, despite his sincerity, should not be trusted completely, and acknowledged KimŌĆÖs efforts to interpret the stele text through comparative analysis of various theories as being fair-minded.

Moreover, seemingly inspired by the scholarly views appended by Kim Such┼Łng, Song Siy┼Ål, six months after writing Chunggak Y┼Åksanbibal, composed Chinj┼Ånch'┼Åpbal, in which he presented his own critical interpretation.

Since ancient times, many scholars have discussed the Yishanbei. However, I believe that the statement by Du Fu µØ£ńö½(712ŌĆō770), "The wildfires burned the stele, and the transmitted script became bloated," should be regarded as the authoritative opinion. According to the analysis by Ouyang Xiu, he first said that it was slightly larger than the Taishanbei µ│░Õ▒▒ńóæ, but later claimed it was slightly smaller. Does this not suggest that the more the carved editions were transmitted, the more the original truth was lost? Now, when one looks at the carved edition reproduced by Kim Such┼Łng, the lean and vigorous vitality of the calligraphy can be said to possess a spirit that communicates with the divineŌĆöcould this not be a copy transmitted before the burning?

I recall that during the Qin dynasty, inscriptions were engraved even on standard weights and measures, as well as on counterweights, bronze plates, and other utensils. These were surely engraved in many places for the purpose of transmission to later generations, such was the custom of the Qin. If so, it is possible that Li Si µØĵ¢» (280ŌĆō208 BCE) created this stele with the same purpose, and even if the original Yishanbei disappeared, there may have been a separate transmission of an authentic version. Otherwise, how could its calligraphy, said to transcend a thousand years, still enable us to glimpse the stylistic gestures of antiquity after the Han and Jin dynasties?

Someone once said, "Even if the steleŌĆÖs script is lean and powerful, what if this is actually the bloated writing that Lao Du referred to? And who can say that the true original was not even leaner and more vigorous?" To this, I responded: that is a fine point. A person may be lean in the past and become plump later, but their skeletal structure and spirit do not change. Now, this seal script shows not even a hairŌĆÖs breadth of resemblance to anything over a thousand years before or after. Therefore, we may truly believe that it originated with Li Si from the beginning.

54

Du Fu once wrote in his Lichao bafen xiaozhuan ge µØĵĮ«Õģ½ÕłåÕ░Åń»åµŁī: ŌĆ£The Yishan Stele was burned by wildfires; the version engraved on jujube wood is bloated and has lost its truth.ŌĆØ Though this verse does not constitute a scholarly verification of the Yishanbei, its vivid imageryŌĆöŌĆ£bloated and has lost its authenticityŌĆØ ĶéźÕż▒ń£×ŌĆöleft a strong impression on Chos┼Ån literati. Song Siy┼Ål also believed Du FuŌĆÖs description was the authoritative view prior to seeing the Yishanbei. But after observing the lean and vigorous script in Kim Suj┼ŁngŌĆÖs reproduction, he began to question the existing scholarly interpretations he had accepted.

Accordingly, Song Siyŏl examined the customs of the Qin period, noting that inscriptions were made not only on weights and measures but also widely on counterweights, bronze plates, and other utensils. Based on this, he hypothesized that Li Si created the Yishanbei for the purpose of transmission and that a genuine exemplar may have separately survived. He further reasoned that the script of the Yishanbei, which had been transmitted over a millennium, displayed no traits of Han or Jin calligraphic styles and that its character forms and visual impression had not changed at all. Based on this intuitive judgment, he concluded that the transmitted Yishanbei was indeed the authentic work of Li Si.

Although Song Siy┼ÅlŌĆÖs textual criticism of the Yishanbei may be overly subjective and lack persuasive rigor, more meaningful than a logically watertight result was his willingness to question previously accepted theories upon seeing a new carved edition and to re-examine and interpret the Yishanbei from a fresh perspective.

Meanwhile, unlike Song Siyŏl, who presented his own critical interpretation in an original manner, most scholars in late Chosŏn accepted the theories of epigraphy scholars such as Ouyang Xiu and Zhao Mingcheng, using historical records as their basis for philological examination of the Yishanbei.

I read the Qin Shihuang benji ń¦”Õ¦ŗńÜćµ£¼ń┤Ć, where the six inscriptionsŌĆöLiangfu µóüńłČ, Langya ńÉģńÉŖ, Zhifu õ╣ŗńĮś, Dongguan µØ▒Ķ¦Ć, Jieshi ńóŻń¤│, and Kuaiji µ£āń©ĮŌĆöwere all recorded. However, the inscription of the Yishanbei was conspicuously absent. It only states that ŌĆ£In the 28th year, the First Emperor ascended Mount Zou and Mount Yi ķäÆÕȦÕ▒▒, erected a stele, and discussed with Confucian scholars of the land of Lu ķŁ»Õ£░ the engraving of the stone to praise the meritorious deeds of Qin.ŌĆØ I also examined the six inscriptions, and in all cases, the beginning of the rhyming section starts with the phrase ŌĆ£the EmperorŌĆØ ńÜćÕĖØ They follow such formulas as ŌĆ£In the twenty-sixth yearŌĆØ õ║īÕŹüµ£ēÕģŁÕ╣┤, ŌĆ£In the twenty-ninth yearŌĆØ ńČŁõ║īÕŹüõ╣ØÕ╣┤, or ŌĆ£In the thirty-seventh yearŌĆØ õĖēÕŹüµ£ēõĖāÕ╣┤, and so forth, forming a clear and structured pattern. Yet in the current version of the Yishanbeiwen ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæµ¢ć transmitted by Xu Xuan ÕŠÉķēē (916ŌĆō991), attributed to Zheng Wenbao ķ䣵¢ćÕ»Č (953ŌĆō1013), the rhyme does not begin with ŌĆ£the EmperorŌĆØ ńÜćÕĖØ, and the year ŌĆ£twenty-sixthŌĆØ is written as ÕŹäÕģŁÕ╣┤, which diverges from the conventions of the six inscriptions.

Du Fu once wrote in his poem

Lichao bafen xiaozhuange µØĵĮ«Õģ½ÕłåÕ░Åń»åµŁī: ŌĆ£The stele of Yishan was burned by wildfires, and the copy engraved on jujube wood became bloated and lost its authenticity.ŌĆØ However, could wildfires truly consume a stone stele? And could a carving on jujube wood be preserved for long? It seems likely that the First Emperor merely erected a stone and discussed the inscription, but in fact, no actual engraving took place.

55

Zhao Mingcheng once questioned the absence of the inscriptional text in the

Shiji ┬Ę

Benji ÕÅ▓Ķ©ś┬ʵ£¼ń┤Ć, noting that although it states that in the 28th year the First Emperor of Qin ascended Mount Zou and Mount Yi and discussed the engraving of a stone with Confucian scholars of the Lu region, no panegyric was recorded, whereas the contents of the other six inscriptions were fully documented.

56 Starting from this doubt raised by Zhao Mingcheng, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng conducted a meticulous investigation into the authenticity of the

Yishanbei. S┼Ång Hae┼Łng compared the textual style of the

Yishanbei inscription with those of the six inscriptions listed in the

Shiji ┬Ę

BenjiŌĆöLiangfu, Langya, Zhifu,

Dongguan, Jieshi, and KuaijiŌĆöand concluded that the

Yishanbei differed in literary form from those exemplars. Specifically, the six inscriptions all begin new rhyme sections with the characters ŌĆ£the EmperorŌĆØ ńÜćÕĖØ, and their year notations follow the formulas ŌĆ£In the twenty-sixth yearŌĆØ ńČŁõ║īÕŹüÕģŁÕ╣┤ or ŌĆ£twenty-sixth yearŌĆØ õ║īÕŹüµ£ēÕģŁÕ╣┤. In contrast, the

Yishanbei omits the ŌĆ£EmperorŌĆØ at the head of new rhyme sections, and the year is written using a different notation, ÕŹäÕģŁÕ╣┤.

While Zhao Mingcheng had raised doubts based on the textual record of the Shiji, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng clarified the distinctions between the Yishanbei and the six inscriptions through close textual comparison, thereby resolving Zhao MingchengŌĆÖs query. Additionally, S┼Ång Hae┼Łng questioned Du FuŌĆÖs poetic lines by asking whether it was possible for a wildfire to burn a stone stele or whether an inscription carved on jujube wood could have been preserved for such a long time.

Conclusion

From a chronological perspective, it is evident that epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts ÕÅżµ¢ćńóæÕĖ¢ began to be introduced in considerable numbers from the late sixteenth century. The interest in epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts during the late Chos┼Ån period stemmed from the enthusiasm for epigraphy and epigraphic compilations. By the mid-seventeenth century, with the introduction of epigraphic works such as Jigulu ķøåÕÅżķīä by Ouyang Xiu and Jinshilu ķćæń¤│ķīä by Zhao Mingcheng, scholars with antiquarian and broad antiquity-oriented dispositions actively engaged in the collection of steles and related rubbings for their antiquarian enjoyment. Thereafter, especially during the reigns of Kings Sukchong, Y┼Ångjo, and Ch┼Ångjo, the reception of evidential scholarship from Qing China led to the full-scale development of epigraphic studies.

As diplomatic missions to the Qing capital brought back antiquarian materials, including epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts, Chos┼Ån envoys with a deep appreciation for epigraphy and calligraphyŌĆösuch as Rangs┼ÅnŌĆÖgun Yi UŌĆöacquired works like Shiguwen, Shenyubei, and Yishanbei. Thus, the enthusiasm for epigraphy that had emerged from the seventeenth century came to encompass epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts as well. It is particularly noteworthy that late Chos┼Ån scholars did not limit themselves to merely describing these artifacts. Rather, they analyzed the characters and text structure in a philological manner, aiming to decipher their meanings.

The Shiguwen, known as the first stone-inscribed poem in Chinese history, attracted significant attention from scholars during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the Chos┼Ån context, extant poetic records by Kim Sish┼Łp indicate that rubbings of the Shiguwen had already been introduced by the fifteenth century. From the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, Chos┼Ån envoys to Beijing made direct rubbings of the Shiguwen or acquired existing rubbings, leading to its widespread circulation. Based on diplomatic mission records, it is evident that Chos┼Ån literati not only described the visual features and preservation state of the Shiguwen, a notable monument in the Qing capital, but also examined its transmission, reflecting a general awareness of textual verification. Moreover, as Chos┼Ån literati tended to cite passages from encyclopedic texts that were widely circulated among envoysŌĆösuch as Rixia jiuwen kao, Daxing xianzhi, and Dijing jingwulueŌĆöthey often produced highly similar accounts.

Although the exact date of the ShenyubeiŌĆÖs entry into Chos┼Ån is not recorded, given that the stele was already widely known during the Ming dynasty and had become the subject of scholarly attention, it can be reasonably inferred that rubbings were introduced sometime during the sixteenth or seventeenth century. According to extant records, the earliest Chos┼Ån figure to encounter the Shenyubei may have been Yun Hyu, whose poetry confirms that the rubbing had reached Chos┼Ån by 1659. Additionally, the importation of the Shenyubei is most explicitly documented in Nangs┼Ån'gun kyemyo y┼Ånhaengnok µ£ŚÕ¢äÕÉøńÖĖÕŹ»ńćĢĶĪīķīä by Yi U, which notes that during the 1663 mission to Beijing, he purchased two copies of the Guzhuan Shenyubei from Wang Yi in the Fengrun area. Based on philological analysis, H┼Å Mok identified the version acquired by Yi U as a rubbing of the stele erected at the Ganquan Shuyuan in Yangzhou during the Jiajing of the Ming dynasty, with an appended colophon titled Shu Ganquan Zishan shuyuan fanke Shenyubei hou by Zhan Ruoshui.

By the eighteenth century, as epigraphic texts from Qing China began entering Chos┼Ån, some Chos┼Ån scholars began to question the authenticity of the Shenyubei, which had previously been regarded as the origin of ancient script forms. Nam K┼Åkkwan was one of the first to raise suspicions about its genuineness and subsequently devalued its scholarly worth. S┼Ång Hae┼Łng, synthesizing the views in Danyanlu by Yang Shen and Jinshiwenziji ķćæń¤│µ¢ćÕŁŚĶ©ś by Gu Yanwu, concluded that all extant versions of the Shenyubei were based on the initial tracing by He Zhi and that the copy brought to Chos┼Ån by Yi U was one of these facsimiles.

Whereas analysis of the Shiguwen and Shenyubei focused on interpreting the content and verifying individual characters, in the case of the Yishanbei, questions of authenticity constituted the central concern. From the time of its introduction, Chos┼Ån literati actively appreciated the calligraphic beauty of the Yishanbei and adopted its style while simultaneously engaging in philological inquiry into its authorship and authenticity. Although the Yishanbei had already been introduced by the fifteenth century, it was not until the seventeenth century that it received significant scholarly and artistic attention in Chos┼Ån. This renewed interest was primarily due to the re-engraving of the stele by Kim Such┼Łng. Some Chos┼Ån scholars reexamined the stele from a fresh perspective, while others extended existing interpretations by further deciphering its text in greater depth.

Translator: Seungchan Bae, Korea University

Notes

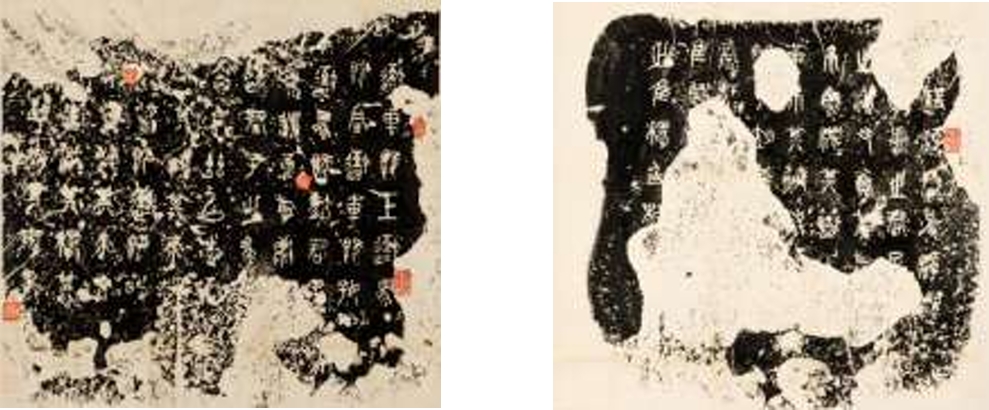

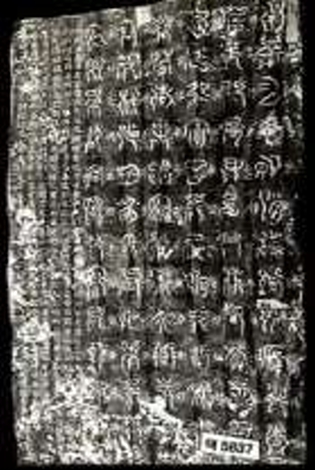

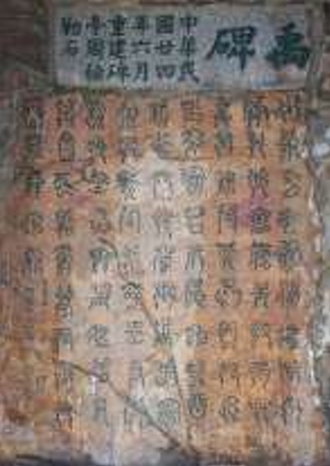

Rubbing of the Shiguwen, National Museum of World Writing Systems

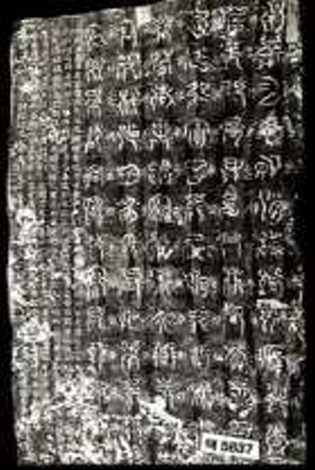

Rubbing of the Shenyu bei (National Museum of World Writing Systems)

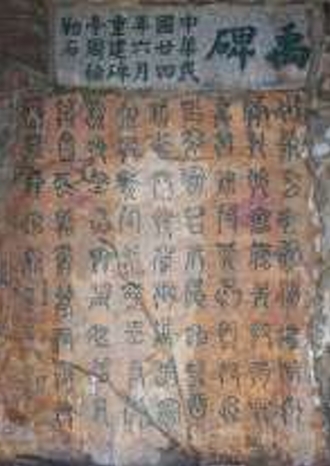

Yuwangbei of Yuelu Shan (Hunan Sheng, Changsha Shi)

Table 1.Authored Works Related to Epigraphic Texts in Chosŏn from the 17th to 19th Centuries

|

Author |

Work |

Category |

|

Yi Huyu┼Ån µØÄÕÄܵ║É (1598ŌĆō1660) |

K┼Łms┼Ångnok ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Collection |

|

Cho Suk ĶČÖµČæ (1595ŌĆō1668) |

K┼Łms┼ÅkchŌĆÖ┼Ångwan ķćæń¤│µĖģńÄ® |

Collection |

|

Yi U µØÄõ┐ü (1637ŌĆō1693) |

Taedong K┼Łms┼Åk S┼Å Õż¦µØ▒ķćæń¤│µøĖ |

Collection |

|

Tongguk My┼ÅngpŌĆÖilchŌĆÖap µØ▒Õ£ŗÕÉŹńŁåÕĖ¢ |

Collection |

|

Taedong K┼Łms┼Åknok Õż¦µØ▒ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Authored work |

|

Unknown |

Che K┼Łms┼Åk chi mun Ķ½Ėķćæń¤│õ╣ŗµ¢ć |

Collection |

|

Kim Such┼Łng ķćæÕŻĮÕó× (1624ŌĆō1701) |

K┼Łms┼ÅkchŌĆÖong ķćæń¤│ÕÅó |

Collection |

|

Unknown |

K┼Łms┼ÅkchŌĆÖ┼Ångwan ķćæń¤│µĘĖńÄ® |

Collection |

|

Nam Hagmy┼Ång ÕŹŚķČ┤ķ│┤ (1654ŌĆō1722) |

ChapkochŌĆÖap ķøåÕÅżÕĖ¢ |

Collection |

|

Rangw┼ÅnŌĆÖgun µ£ŚÕĤÕÉø (1640ŌĆō1699) |

Haedongjipkorok µĄĘµØ▒ķøåÕÅżķīä |

Collection |

|

Cho K┼Łn ĶČÖµĀ╣ (1631ŌĆō1690) |

Punggyemallok µźōµ║¬µ╝½ķīä |

Authored work |

|

Unknown |

K┼Łms┼Åkki ķćæń¤│Ķ©ś |

Collection |

|

Kim Chae-ro ķćæÕ£©ķŁ» (1682ŌĆō1759) |

K┼Łms┼Åknok ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Collection |

|

Yu Ch'┼Åkki Õģ¬µŗōÕ¤║ (1691ŌĆō1767) |

K┼Łms┼Åknok ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Collection |

|

Taedong K┼Łms┼ÅkchŌĆÖap Õż¦µØ▒ķćæń¤│ÕĖ¢ |

Collection |

|

K┼Łms┼Åkchongmok ķćæń¤│µŹ┤ńø« |

Authored work |

|

Unknown |

Haedong K┼Łms┼Åknok µĄĘµØ▒ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Authored work |

|

Pak Chiw┼Ån µ£┤ĶČŠµ║É (1637ŌĆō1805) |

K┼Łms┼Åknok ķćæń¤│ķīä |

Authored work |

|

Yun Tongs┼Åk Õ░╣µØ▒µÖ│ (1718ŌĆō1798) |

Noyun Samgwan tŌĆÖong ĶĆüĶĆśõĖēÕ«śķĆÜ |

Authored work |

|

S┼Å Yuku Պɵ£ēµ”ś (1764ŌĆō1845) |

Tongguk K┼Łms┼Åk µØ▒Õ£ŗķćæń¤│ |

Authored work |

|

Yu Ponye µ¤│µ£¼ĶŚØ (1777ŌĆō1842) |

Suh┼Ån PangpŌĆÖinok µ©╣Ķ╗ÆĶ©¬ńóæķīä |

Authored work |

|

Unknown |

Tongguk K┼Łms┼ÅkpŌĆÖy┼Ång µØ▒Õ£ŗķćæń¤│Ķ®Ģ |

Authored work |

|

Yi Chomuk µØÄńź¢ķ╗Ö (1792ŌĆō1840) |

Nary┼Å Imnangko ’żÅķ║ŚńÉ│ń滵öĘ |

Authored work |

|

Pang H┼Łiyong µ¢╣ńŠ▓ķÅ× |

Yew┼Ånjinch'e ķÜĖµ║ɵ┤źķĆ« |

Authored work |

|

Yi Yuw┼Ån µØÄĶŻĢÕģā (1814ŌĆō1888) |

Ky┼Ångju Isi K┼Łms┼Åknok µģČÕĘ×’¦Īµ░Å’żŖń¤│ķīä |

Authored work |

|

K┼Łmhaes┼ÅngmokkpŌĆÖy┼Ån S┼Å ķćæĶ¢żń¤│Õó©ńĘ©Õ║Å |

Authored work |

|

Kim Py┼Ångs┼Ån ķćæń¦ēÕ¢ä |

K┼Łms┼ÅkmokkŌĆÖoram ķćæń¤│ńø«µöĘĶ”Į |

Authored work |

|

O Ky┼Ångs┼Åk ÕÉ│µģČķī½ (1831ŌĆō1879) |

Samhan K┼Łms┼Åknok õĖēķ¤ōķćæń¤│ķīä |

Authored work |

|

S┼Å SangŌĆÖu ÕŠÉńøĖķø© (1831ŌĆō1903) |

Nary┼Å PangpŌĆÖinok ńŠģķ║ŚĶ©¬ńóæķīä |

Authored work |

Table 2.Colophons, Inscriptions, and Prefaces on epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts in Chosŏn from the 17th to 19th Century

|

Author |

Colophons, Identifications, Prefaces |

Epigraphic rubbings of ancient texts |

|

H┼Å Mok Ķ©▒ń®å (1595~1682) |

Samdaegomunbal õĖēõ╗ŻÕÅżµ¢ćĶĘŗ |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ, Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć, Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

Hy┼Ångsan Shinubibal ĶĪĪÕ▒▒ńź×ń”╣ńóæĶĘŗ |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ |

|

Song Siy┼Ål Õ«ŗµÖéńāł (1607~1689) |

Chunggak Y┼Åksanbibal ķćŹÕł╗ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæĶĘŗ |

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

Chinj┼Ånch'┼Åpbal ń¦”ń»åÕĖ¢ĶĘŗ |

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

S┼Å S┼Åkkoch'┼Åp'u µøĖń¤│ķ╝ōÕĖ¢ÕŠī |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Yi Manbu µØÄĶɼµĢĘ (1664~1732) |

S┼Å Isasoj┼ÅnchŌĆÖ┼Åp µøĖµØĵ¢»Õ░Åń»åÕĖ¢ |

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

Pak T'ae-mu µ£┤µ│░Ķīé (1677~1756) |

Inurong Soj┼Łngdae'u P'y┼Ångsut'oj┼Åns┼Å µØÄĶ©źń┐üµēĆĶ┤łÕż¦ń”╣Õ╣│µ░┤Õ£¤ń»åÕ║Å |

Dae'u P'y┼Ångsut'oj┼Ån Õż¦ń”╣Õ╣│µ░┤Õ£¤ń»å |

|

An My┼Ång-ha Õ«ēÕæĮÕżÅ (1682~1752) |

Uj┼Ån By┼Ångp'unggi ń”╣ń»åÕ▒øķó©Ķ©ś |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ |

|

Yi Kichi µØÄÕÖ©õ╣ŗ (1690~1722) |

S┼Åkkoch'┼Åps┼Å ń¤│ķ╝ōÕĖ¢Õ║Å |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Yi Kwang-sa µØÄÕīĪÕĖ½ (1705~1777) |

Non Y┼Åksanbi Ķ½¢ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

Nam Kong-ch'┼Ål ÕŹŚÕģ¼ĶĮŹ (1760~1840) |

U PŌĆÖy┼Ångsut'ochŌĆÖan S┼Åkk┼Åk ń”╣Õ╣│µ░┤Õ£¤Ķ┤Ŗń¤│Õł╗ |

Dae'u P'y┼Ångsut'oj┼Ån Õż¦ń”╣Õ╣│µ░┤Õ£¤ń»å |

|

Chiny┼Åksan Gaks┼Ångmukkak ń¦”ÕȦÕ▒▒Õł╗ń¤│Õó©Õł╗ |

Yishanbei ÕȦÕ▒▒ńóæ |

|

Chibusan Gaks┼Ångmukpon õ╣ŗńĮśÕ▒▒Õł╗ń¤│Õó©µ£¼ |

ChibuGaks┼Åk ĶŖØńĮśÕł╗ń¤│ |

|

Yi S┼Å-gu µØĵøĖõ╣Ø (1754~1825) |

S┼Åkko S┼Å ń¤│ķ╝ōÕ║Å |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

S┼Ång Hae┼Łng µłÉµĄĘµćē (1760~1839) |

Che S┼Åkkomunhu ķĪīń¤│ńÜʵ¢ćÕŠī |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Shinyubibal ńź×ń”╣ńóæĶĘŗ |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ |

|

S┼Å Yuku Պɵ£ēµ”ś (1764~1845) |

S┼Åkkomuns┼Å ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ćÕ║Å |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Hong Ky┼Ångmo µ┤¬µĢ¼Ķ¼© (1774~1851) |

Imjang Jos┼Åkkoga Ķć©Õ╝Ąńģ¦ń¤│ķ╝ōµŁī |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Chus┼Åkkomun Gubon Õæ©ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ćĶłŖµ£¼ |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

S┼Åkkow┼Ån sinp┼Ån ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ćµ¢░µ£¼ |

Shiguwen ń¤│ķ╝ōµ¢ć |

|

Yang Chiny┼Ång µóüķĆ▓µ░Ė (1788~1860) |

S┼Å KorupŌĆÖipŌĆÖanhu µøĖÕ▓ŻÕČüńóæµØ┐ÕŠī |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ |

|

Han Uns┼Ång ķ¤ōķüŗĶü¢ |

Ky┼Ångs┼Å Uch┼Ån hu µĢ¼µøĖń”╣ń»åÕŠī, Ch┼Ång Im My┼Ångno, Ķ┤łõ╗╗µśÄĶĆü |

Shenyubei ńź×ń”╣ńóæ |

- ChŌĆÖoe, Y┼Ångs┼Ång. ŌĆ£Han'gukk┼Łms┼Åk'ag┼Łi s┼Ångnipkwa palch┼Ån-y┼Ån'gusa┼Łi ch┼Ångni-ŌĆØ ķ¤ōÕ£ŗķćæń¤│ÕŁĖņØś ņä▒ļ”ĮĻ│╝ ļ░£ņĀäŌĆöńĪÅń®ČÕÅ▓ņØś µĢ┤ńÉå ŌĆö.ŌĆØ Tongyanggoj┼Åny┼Ån'gu 26 (2007): 381-412.

- Cong Wenjun. Zhongguo shufashi xianqin Qindai juan õĖŁÕ£ŗµøĖµ│ĢÕÅ▓┬ĘÕģłń¦”ń¦”õ╗ŻÕŹĘ. Nanjing: Jiangsu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2021.

- Han, Minch┼Ång. ŌĆ£H┼Åmokkwa igwangsa┼Łi pokko┼Łishige taehan koch'alŌĆØ Ķ©▒ń®åĻ│╝ ’¦ĪÕīĪÕĖ½ņØś ’ź”ÕÅżµäÅĶŁśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĶĆāÕ»¤.ŌĆØ S┼Åyebip'y┼Ång 4 (2009): 67-86.

- H┼Å Pong. ŌĆ£Choch'┼Ån'giŌĆØ µ£ØÕż®Ķ©ś. In Y┼Ånhaengnokch┼Ånjip 6. Seoul: Dongguk University, 2001.

- H┼Å Mok. ŌĆ£Kiy┼ÅnŌĆØ Ķ©śĶ©Ć. In HanŌĆÖguk munjip chŌĆÖonggan 98. Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, 1988.

- Hong ┼Änch'ung. ŌĆ£UamjipŌĆØ Õ»ōÕ║Ąķøå. In HanŌĆÖguk munjip chŌĆÖonggan 18. Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, 1988.

- Hong Taeyong. Tamh┼Åns┼Å µ╣øĶ╗ƵøĖ. Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, 1989.

- Hong Yangho. ŌĆ£IgyejipŌĆØ ĶĆ│µ║¬ķøå. In Han'guk y┼Åktaemun jipch'ongs┼Å 783-788. Paju: Ky┼Ånginmunhwasa, 1993.

- Hwang, Ch┼Ångy┼Ån. ŌĆ£Nangs┼Ån'gun iu, 17segi changshik'an yesul aehogaŌĆØ ļéŁņäĀĻĄ░ ņØ┤ņÜ░, 17ņäĖĻĖ░ ņןņŗØĒĢ£ ņśłņłĀ ņĢĀĒśĖĻ░Ć.ŌĆØ Naeir┼Łl y┼Ån┼Łn y┼Åksa 38 (2010): 212-229.

- Hwang, Ch┼Ångy┼Ån. ŌĆ£Nangs┼Ån'gun iu┼Łi s┼Åhwa sujanggwa p'y┼Ånch'anŌĆØ ļéŁņäĀĻĄ░ ņØ┤ņÜ░ņØś ņä£ĒÖö ņłśņןĻ│╝ ĒÄĖņ░¼.ŌĆØ Changs┼Ågak 9 (2003): 5-44.

- I Kichi. ŌĆ£Iramy┼ÅnŌĆÖgiŌĆØ õĖĆÕ║ĄńćĢĶ©ś. In Han'guk anmuny┼Ån haengmun h┼Åns┼Ån p'y┼Ån 12-13. Fudan University, 2011.

- Kang Sehuang. ŌĆ£PŌĆÖyoamyugoŌĆØ Ķ▒╣ĶÅ┤ń©┐. In HanŌĆÖguk munjip chŌĆÖonggan 80. Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, 2009.

- Kim Kis┼Łng. Han'guks┼Åyesa ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņä£ņśłņé¼. Seoul: Ch┼Ång┼Łmsa, 1975.

- Kim Such┼Łng. ŌĆ£Mun'gokchipŌĆØ µ¢ćĶ░Ęķøå. In Han'guk y┼Åktae munjip ch'ongs┼Å 2326-2329. Paju: Ky┼Ånginmunhwasa, 1997.